Why our communities desperately need idealistic, ramshackle places like DIY Space For London

Constantly under financial and legislative threat, underground culture needs us fighting for these venues

“This place is fucking great. There are literally signs on the wall that tell you not to be a cunt.”

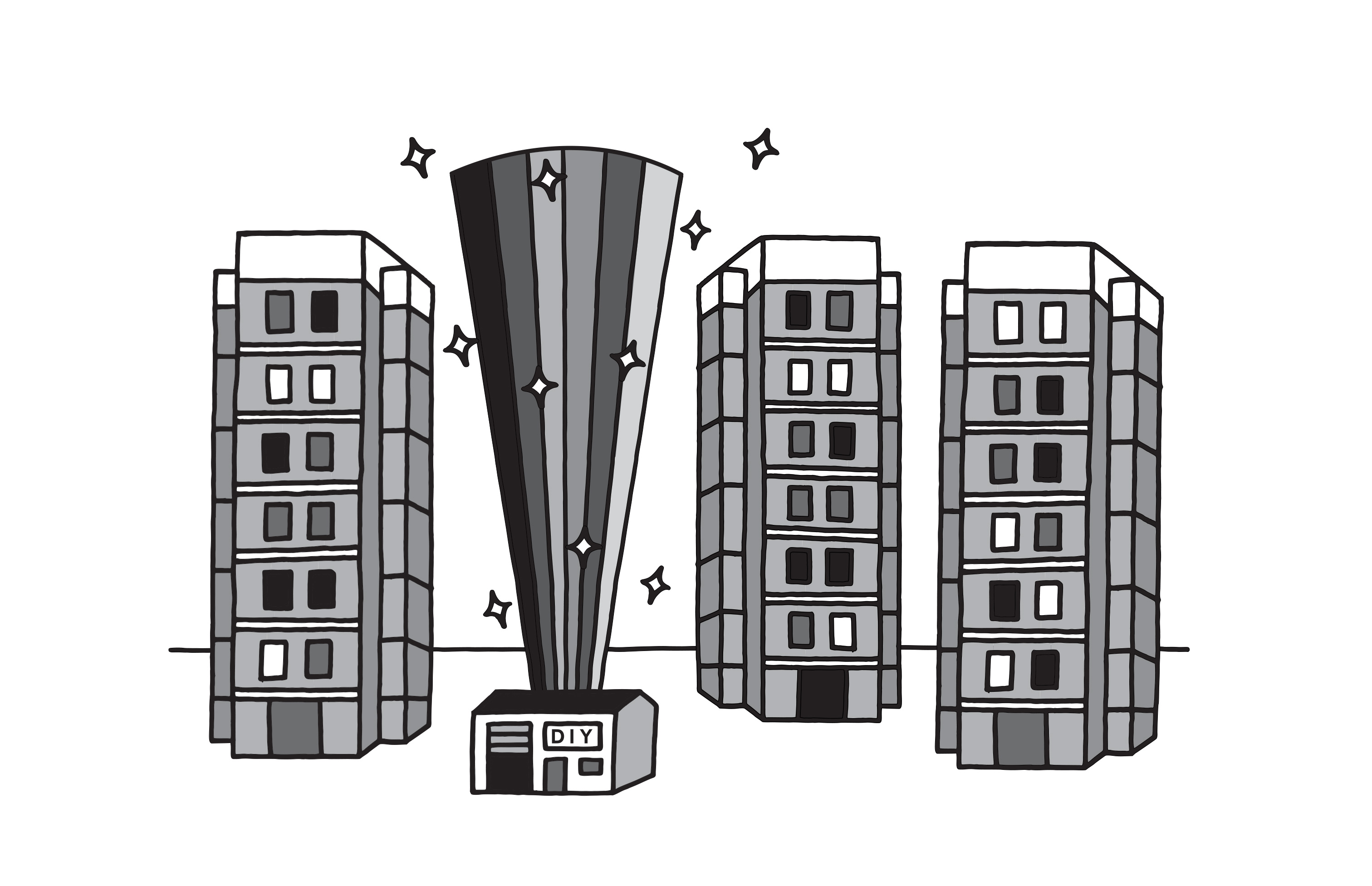

Ronan Kehoe, of Essex punks Don’t Worry, doesn’t mince his words. He’s right, though, in his mid-gig address: South Bermondsey’s DIY Space for London is fucking great. Built into an industrial unit in the shadow of three hulking residential tower blocks, the deceptively pastoral-sounding Windermere, Grasmere and Ambleside Points, this subcultural hive just off the Old Kent Road has become an institution in the three short years since its opening. Solely volunteer-run, it’s the kind of venue that’s few and far between these days. In truth, places like this probably always have been pretty rare, so distinctive is its entirely grassroots, non-profit ethos, and so dear to so many hearts has it become.

I live just around the corner from DSFL, a short walk away across an area of semi-landscaped wasteland known as “the meadow”. Yet there’s something about this place that feels a long way away. Perhaps it’s a matter of mental, rather than physical, space: from the moment you enter the venue, you are, to paraphrase Kehoe, discouraged from being a cunt. Posters throughout the venue remind visitors that any form of discrimination or harassment will not be tolerated, that people have different definitions of personal space and social customs, and that providing an environment in which members of under-represented groups may have their voices heard is a top priority here.

There are very concrete financial and legislative threats to these kinds of spaces, and along with them the kinds of underground culture that are only able to develop in environments that actively promote difference, openness, and inclusion. In February 2018, the first UK live music census found that a third of the UK’s small venues outside London were struggling to survive in the face of increasingly stifling noise restrictions, extortionate business rates and cuts to arts funding. In the capital, a city groaning under the weight of its grotesque property bubble, such issues are even more acute. In September 2018, the core group of DSFL volunteers made an emergency plea for financial help, prompted by a grim fiscal forecast that predicted that the venue would not be generating enough income by November to pay that month’s rent. A fundraising drive ensued, and the DSFL coffers were temporarily refilled. This is not, however, a long-term solution.

Something about the tower blocks near DSFL has lodged deep into my subconscious. They feature in my dreams regularly, sometimes as mere setting, other times as near-protagonists. A friend of mine once described them as “nightmare fuel”; although their appearance in my dreams is as often benign as it is sinister, that label was hammered home emphatically by a recurring nightmare I had last year.

I’m at a trendy party in a top-floor flat in one of Peckham’s more bijou apartment buildings. To the north-east, across the great dirty artery of the Old Kent Road, stands Windermere Point, silhouetted against a rich, liquid sunset like the helicopters on the theatrical poster for Apocalypse Now. Then, as the partiers sip their cocktails and make designer smalltalk, a graphic atrocity, which I won’t describe further here, is inflicted upon the three towers. I scream, run to the window, and begin to cry uncontrollably as I picture the people inside. Everyone else shrugs and returns to their conversations.

I awake in a sweat. A few weeks later, I have the same nightmare again. A few more weeks on, the Grenfell Tower disaster happens. The dreams just keep coming for a long while after that.

South-East London in 2018 is a place in flux, whose inequalities are being brought into increasingly sharp relief by a constant flow of capital from the public purse into the private pocket. As arts funding is cut and grassroots cultural centres close, property prices continue to rise. As a white, heterosexual male who moved to the area for university, I’m hardly the person who will be worst affected by the excesses of gentrification; not only that, but it’s hard to ignore the nagging feeling that my mere presence here makes me a cog in that machine.

Yet places like DIY Space for London, situated at the foot of the tower blocks upon which many of my anxiety dreams focus, give me hope, and I’m not the only one. Inside, people of all backgrounds are not only welcome, but actively encouraged to participate in this community in whatever way they feel comfortable. And they take it seriously: each member, volunteer, promoter and tech is read the venue’s regulations at the beginning of each event, and is obliged to become familiar with the place as a breeding ground for kinds of self-expression that are rarely so respected elsewhere. A typical week on the DSFL calendar will feature punk, noise, drag, yoga, screen-printing workshops, zine club socials and more. You don’t get that at your local O2 Academy.

Importantly, DSFL’s resistance to gentrification is characterised more by hope than nihilism, offering an alternative vision of communities working together in the service of common goals. It’s idealistic, a little ramshackle, and we really fucking need it.