The lonely coastal hallucinations of The Shadow Ring

A deep dive into the seaside isolation and unheimlich genius of a uniquely obtuse cult classic

We are all recluses now. The theme of isolation has inevitably permeated the landscape of music journalism and its thinkpieces. Yet isolation and reclusion has its own rich history in (un)popular music, that long predates the current crisis.

It is this loneliness, combined with the inane boredom that goes hand-in-hand with the angst of the young, that can spur artists into uncharted waters. This heady cocktail of stark isolation can be reached by anyone, anywhere, but certain parts of the world lend themselves to it more than others.

There’s a particular and manic loneliness inbuilt to the small towns of the English coast. While its beauty is on show for all to see in the summer, there’s an unrelenting bleakness to coastal towns in the winter. All that is joy is swamped by the menace of black skies and the occasional glimpse of lightning on the offing.

I grew up in Southampton, with relatives and friends towards Brighton and Bournemouth from the smaller towns along the coast. The summers are beautiful. The winters, not. I am aware that this is my own experience of the England’s coast, however; in a bigger city there will always be things to do, football teams to support, music scenes to immerse yourself in, cinemas to go to.

Yet the loneliness, apathy and involuntary solitude would be amplified by a thousand had I grown up in a smaller town, like many friends and acquaintances. As the final rays of summer sun slink away once more, the world would shrink; chocolate box idealism inverted. There are eight months a year through which tourists fear to tread, and a very particular isolation is induced. Coupled with a spirit-crushing boredom, this reclusion makes the coast a bleak place to call home during the off season.

It becomes a fantasy to get out of the house

Hold Onto I.D. is a 1997 album that taps into this mindset and typifies this feeling of isolation and boredom aptly. Like no other, it thrives in these circumstances, fuelled by tedium and enchanted by the mundane.

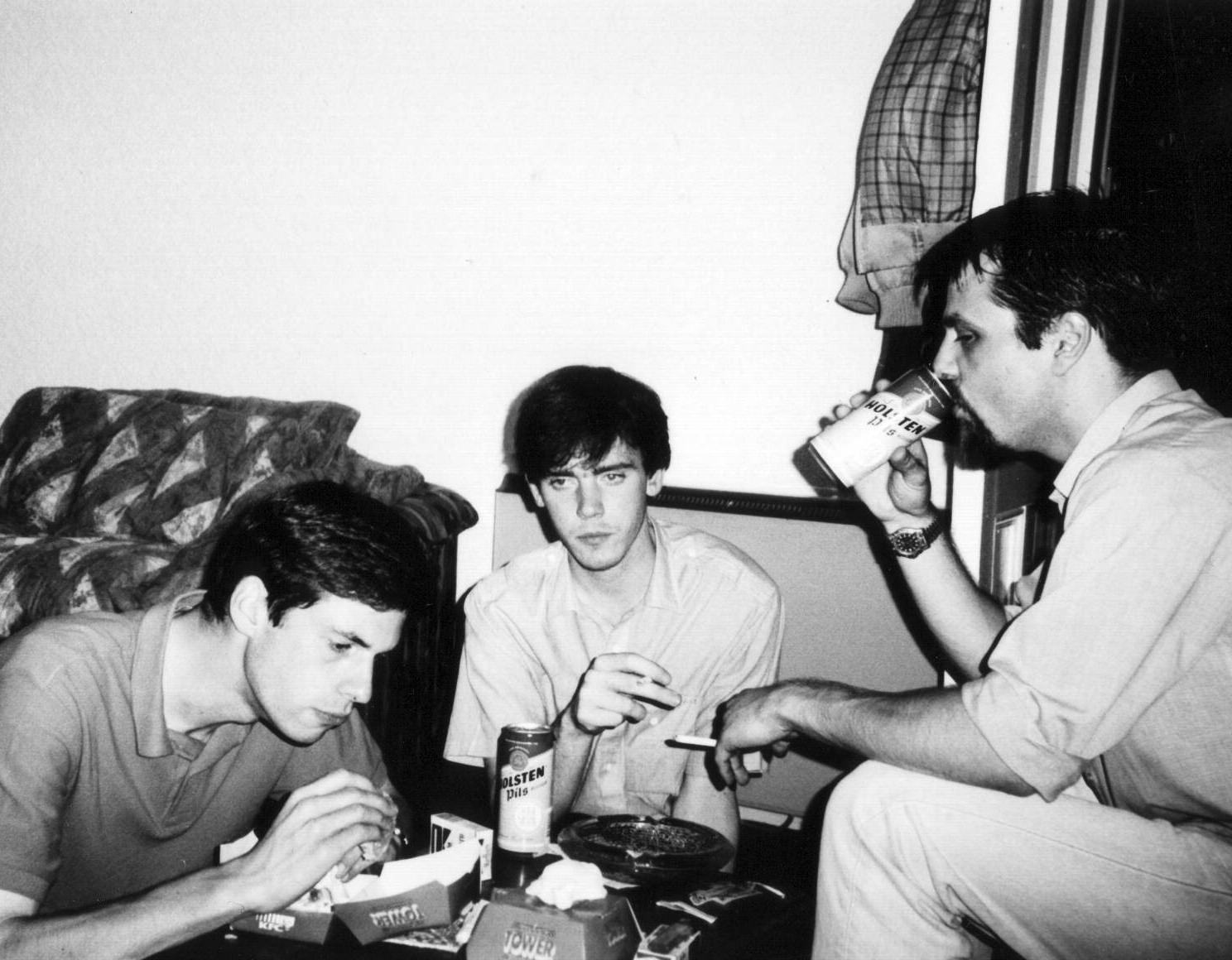

From 1993 to 2003, Tim Goss, Darren Harris and Graham Lambkin plied their musical trade as The Shadow Ring. A group birthed out of nascent, adolescent small-town tedium, the band formed in their late teens, and over nine albums turned this paranoid angst into something entirely surreal.

The Shadow Ring’s discography is the product of frustration, boredom and coastal loneliness. Their music owes a huge debt to its setting. The band are from Folkestone, a seaside town in Kent. It has idyllic parts and parts steeped in maritime history. It’s exactly the kind of place described above.

The discography is littered with all kinds of alienated yet vital avant-pop esoterica. Debut City Lights is a DIY affair: amateur musicianship mangles with all sorts of sounds that one might make searching their kitchen for percussion. On Cape of Seaweed Lambkin’s voice wanders throughout a lonely, cold dystopia created by repetitive acoustic guitar lines and bashed kitchen utensils. In the background, submerged by detuned guitar twang, the dialogue, “You know what I love?”, “Yeah”, “It’s my cape of seaweed”, can just about be made out.

1999’s epochal Lighthouse, which warrants a long-read unto itself, is a loose concept album set around the quintessential symbol of seaside loneliness; a dismantling of the signature sound they’d built up over the course of their first few albums. Among a fizzing soundbed, Harris and Lambkin weave their angular allegories, leaving coughs and stammers in amongst the wonk of undomesticated synthesisers.

But it’s on days like this (quarantined, exiled) that Hold Onto I.D. hits like no other. It is not just my favourite album by The Shadow Ring, it may be my favourite album ever. It is the halfway point between the homemade experiments of City Lights and the sharp left turn of Lighthouse.

Across seven tracks, the trio conjure something that is dark and fantastical; perhaps a kind of music that could be made nowhere but a town on the English coast. Recorded largely in the band’s living quarters – Coombe House – Hold Onto I.D. was released in 1997, but has a certain timeless quality to it.

Everyday strange

Graham Lambkin’s poetry is the focal point; it drags the record from room to room. Hold Onto I.D. is a loose concept album set in a house under attack from “shrimps and nautical foes”, the elements of the sea wreaking wild havoc on red bricks. “You’ve got to learn the difference between sweat, and dew,” heeds Darren Harris, as he grumbles foreboding tales of “black lakes” appearing on the floor. His spoken word delivery is stern and unflinching, each line is as serious as your life.

The constant allusions to household items, to dusty brown rugs and carpets, make The Shadow Ring’s take on surrealism so tangible and so tactile. Like Mark E. Smith before them, Lambkin’s words and Harris’ voice create a kind of unheimlich everyday strange.

Bashed kitchenware

Lots of the lyrics not only paint a very visceral picture but act as a Haynes manual for those that might find themselves in a similar situation. “Parsnips in shower caps are not all that common, and I can’t recall the last time that fruit or harvest produce volunteered to put on its bathing costume…” utters Harris: “Keep them underwater and wash what you eat.” I listen to this as every day I wash every item I eat. When I listen to this album, I picture three men my age in ’90s suburbia telekinetically transmitting their seaside apathy a third of the way around the English coast.

The lyrics are special, but it is only when they are combined with the sound of Hold Onto I.D. that The Shadow Ring come into their own. Terse guitars are played simply; descending melodies that are part Slint and part Syd Barrett, with little regard for musical precision. Meanwhile, Tim Goss’ synthesiser is a constant soundbed, high-pitched whistles and the percussion sounds come from frantically bashed boxes kitchenware.

The microphone says enough is enough

On ‘Like When’, a percussive fanfare that sounds like the frantic knock of the door meets red-eyed drones and a miasma of tape loops. Meanwhile, the outro is laden with the tortured moan and wrathful growl of the detuned violin. The suspicious eyes of the band turn onto their neutral collaborators, their instruments. “The microphone says enough is enough, I’ll work with better bands,” spits Harris.

The songs never have climaxes, they merely pace back and forth in their paranoia spheres. Each song comes in with a malignant swagger, and simply maintains the same level of novel menace. It is this spectral approach to songwriting that makes Hold Onto I.D. unlike any album before or since.

Perhaps the best example of this is ‘Watch the Water’, the album’s brooding opener. We’re ushered into the nightmare realm of The Shadow Ring by a taut guitar riff before Harris stammers, “it becomes a fantasy to get out of the house”, and the group drift into a phantasm of nautical DIY noise. Echoing footstep drums and the slumped Pajo riff meet a buzz saw synth and the band’s marine apparitions are fully realised.

Hold Onto I.D. is a record that holds a special place in my heart, and in the current climate it’s a constant berth in my music library. The band’s oddball sound is often described as some kind of avant-anti-music, but on this album we are allowed a wholly accessible peek into another world. For all the obtuse lyricism and abject desire to not conform to any preconceived notions of “what a band is”, The Shadow Ring’s 1997 masterwork is as instantaneous a hallucinatory music experience as any other.