Radiohead’s ‘OK Computer’ would be nothing without ‘Kid A’ – stick with us on this

Maybe not nothing... but its 20-year-old bulletproof critical respect owes a lot to what followed

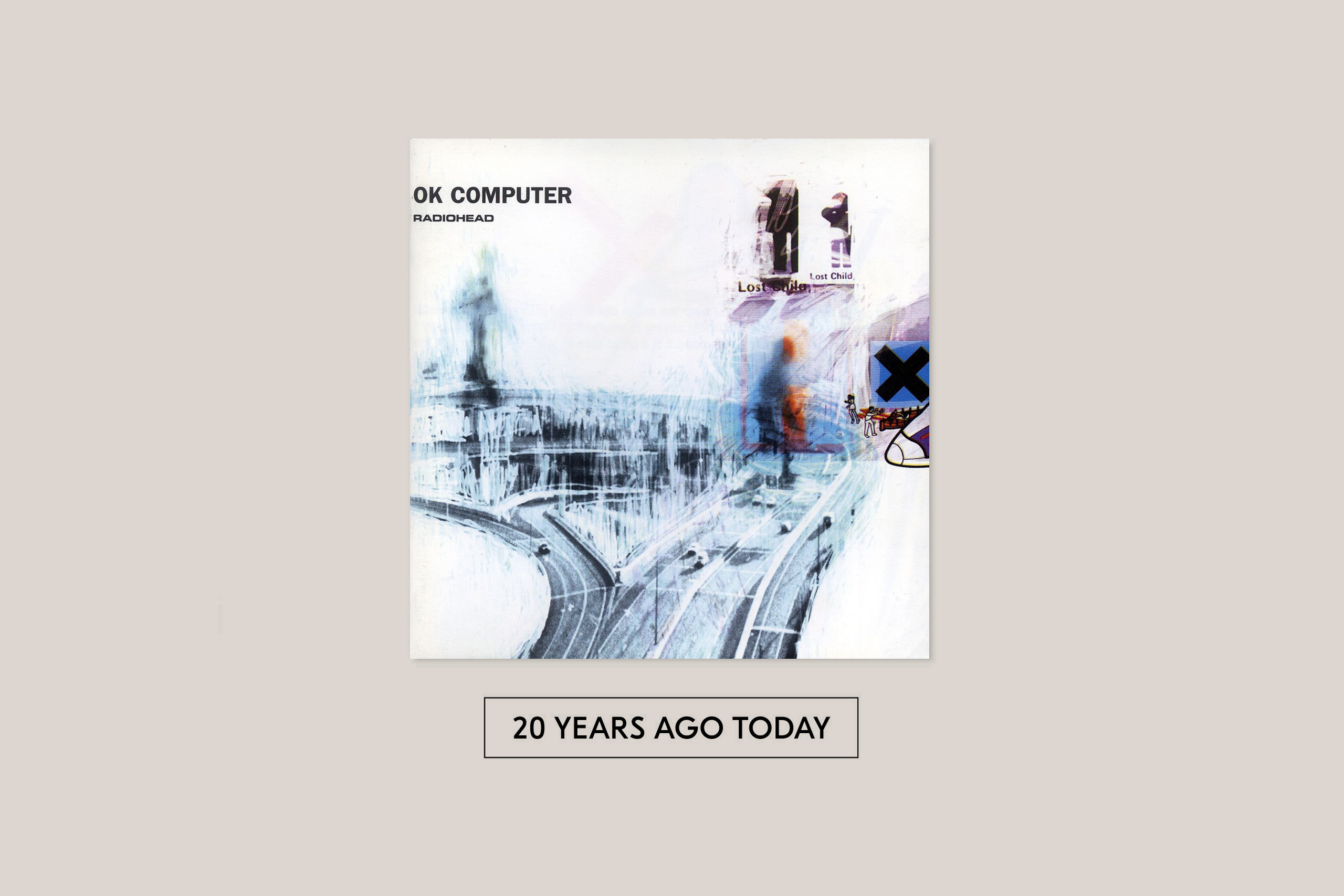

‘OK Computer’ wasn’t allowed to be merely Radiohead’s third album for long. Instead, within days of its release, it was being greeted almost universally by reviews that didn’t choose just to compliment it but also wanted to find it instantly totemic, of cultural and historic note far beyond its status as simply the latest addition to a then decent anthemic rock band’s fledgling discography.

And so it went that commentary across the UK music press in June 1997 bestowed ‘OK Computer’ with the sort of long-term significance that had last been used on ‘Sgt Pepper’, with critics citing the album as the definitive articulation of the age – of pre-millennial angst, of information overload, of capitalist homogeneity and of any other late-90s -osis that was starting to gnaw as the Y2K loomed. Before most of the general public had even had a chance to hear the album, Select called it “mould-breaking”, the NME heralded “one of the greatest albums of living memory, distancing Radiohead from their peers by an interstellar mile”, and the Guardian said it was “destined to be recognised as one of the definitive records of all time”.

Come Christmas, it came first or second in nearly every year-end roundup and, in perhaps the most breathless display of hysteria surrounding the record’s early life, a reader’s poll in the January 1998 issue of Q saw ‘OK Computer’, then barely six months old, edge out ‘Revolver’ as the best album of all time. And with that, it seems, the dye was cast: ‘OK Computer’ was now shorthand for perfection, emblematic of greatness, no longer capable of being assessed purely as a piece of pop music.

However, where early hype for an album is often later dismissed as over-enthusiasm (see how, for example, those thunderstruck five-star reviews of ‘Be Here Now’ have been quietly rescinded over time), reverence for ‘OK Computer’ has endured, and even hardened, in the past twenty years, to the extent that in 2017 the only criticism of the album is found in wilfully contrary “sacred cow”-style takedowns.

What has futureproofed it so brilliantly, though, is less its intrinsic value as a magnificent record – simultaneously prescient, relatable and imposing – and more what Radiohead chose to do next. And so, on its twentieth birthday, the easiest identified influences on why ‘OK Computer’ is still hailed as a masterpiece are, perhaps paradoxically, its successors, which imbue the album with a sense of purity and poignancy no contemporary critic could have predicted: only through the prism of ‘Kid A’, ‘In Rainbows’ and ‘A Moon Shaped Pool’ in particular does ‘OK Computer’ actually live up to its billing, feeling like the end of something and precursor for something else, both a bridge and a monolith, and a final statement.

On a song-by-song level, there’s foreshadowing everywhere here: it’s difficult to hear ‘Airbag’’s jerking rhythm section without imagining the spectres of ‘Idioteque’ or ’15-Step’ auditioning their parts just out of earshot. Likewise, the cynical sloganeering cut-ups of ‘Fitter Happier’ lay the groundwork for ‘Kid A’’s lyrical non-sequiturs, and one can clearly hear the germ of ‘Everything In Its Right Place’ within ‘Subterranean Homesick Alien’’s disquieting Rhodes piano.

The subsequent publishing, too, of ‘Motion Picture Soundtrack’ and ‘True Love Waits’ – perhaps the two finest album closers Radiohead have ever written, and both in existence at the time of ‘OK Computer’’s recording – serve to emphasise ‘The Tourist’’s perfection as the album’s final statement.

On a broader level, too, Radiohead’s disappearance down rabbit holes of electronic experimentation from ‘Kid A’ onwards gives ‘OK Computer’ an end-of-an-era status: never again will they try to write a song as towering as ‘Karma Police’, as direct as ‘No Surprises’ or as formally complex as ‘Paranoid Android’. If they had – and their subsequent six albums had pursued increasing stadium-rock scale at the expense of artistic impact in the vein of, say, U2 – it’s easy to imagine a sense of bombast fatigue setting in that retrospectively infected the reading of their entire output. As it is, one of the easiest things to cherish about ‘OK Computer’ twenty years on is that it’s the last time the band went an entire album without wilfully trying to confound. Indeed, in that sense, it’s also a marker of the last time they were entirely on the same side as their fans, and that good will only embalms the album more as the years progress.

Most importantly, though, ‘OK Computer’ is the only deliberately perfect album from a band that, you sense, strives for perfection (regardless of the ugliness with which Thom Yorke views ambition), something that’s solidified with each new flawed Radiohead record. That sets it apart from the rest of the band’s work: other moments within their discography match might ‘OK Computer’ (‘Kid A’’s triple-distilled incarnation of ‘OK Computer’’s electronic burbles and paranoia is arguably even more impressive, despite its inconsistencies), but whenever they do they feel stumbled upon. By contrast, there are few albums anywhere in the canon that have as much of a sense of fulfilled purpose, of played-for-and-got, as this one.

In its review from the time, Mojo wrote that “in 20 years time ‘OK Computer’ will be seen as the key record of 1997, the one to take rock forward, instead of artfully revamping images and song-structures from an earlier era”. While that piece was broadly right in recognising the increasing tedium of Britpop, the idea that ‘OK Computer’ would take rock forward is an interesting one. On one level, it did: without it, there certainly would be no Muse, Coldplay, Arcade Fire or all manner of other post-millennial big-budget festival headliners. What was perhaps more difficult to foresee was that while Radiohead would set a new path for rock music, they wouldn’t follow it themselves. That, in hindsight, could be the finest artistic decision of their career; after all, it’s that act more than any other that has cemented OK Computer’s legacy most firmly, fulfilling a fate that everyone wished upon it from birth.

Also out this week in 1997:

Spiritualized – Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space (Dedicated). Chart peak #4

To read all the other entries in Sam’s Twenty Years Ago Today blog, click here.