Most people’s careers end in Vegas – Gwenno’s started there, in an Irish dance phenomenon

For our Sweet 16 column, the Welsh artist recalls leaving home to star in Lord of the Dance and immerse herself in the world of techno

For our Sweet 16 column, the Welsh artist recalls leaving home to star in Lord of the Dance and immerse herself in the world of techno

Gwenno: My teens are a tale of two halves. The first half was completely chaotic – my parents divorce and I go to live with my mum. She’s got three jobs to pay for us to go Irish dancing and stuff. School’s an utter nightmare – I’m getting into all sorts of trouble and just being very angry and frustrated and alone, as all teenagers tend to be. And then I go to Dublin when I’m 15 for an audition for Lord of the Dance [the blockbuster musical and Irish dance show created by Michael Flatley] and I get the job. So I go to London, to Pineapple Studios for six weeks, and then I’m in Sydney Arena. That was my first gig. And then I’m in Vegas. And all of a sudden, everything works out. It was so chaotic before that point, and then everything fell into place as I turned 16.

When I get to Las Vegas, the big thing that happens is, I’m in this big group of people. We all lived in these apartments seven miles from the Strip, and a lot of the girls came from Belfast. This is 1998, and they’re coming from a warzone, basically. And they’re telling us about how they go clubbing and how the Protestants and Catholics are all together and they take pills and it’s amazing. And there’s a club in Vegas called Utopia, so we all started going there. We’re working two shows a night, five days a week, and on a Saturday night we’d go to Utopia and techno nights. That was our weekend. I hadn’t been clubbing until then, and having that experience after all the chaos that had come before it, it was like, “Ah! Everybody’s one thing!” It was almost like a religious experience on the dance floor – you’re not alone. It was a very dramatic experience, but it’s like you’re finding the truth with other people, and music is the binding thing. I was finding truth in the middle of the desert.

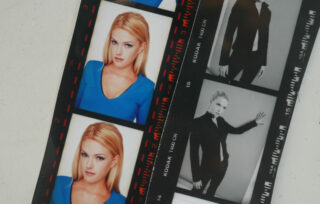

I was the lead part in the show, with my face on the side of buses. It was interesting and restricting – I was playing a role, and the gender binaries in that show were so old-fashioned and patriarchal. When I think back to the story now, I think, “What the hell is this!?” And it was strict – we had this really horrible choreographer who told us we were all overweight, so everyone had an eating disorder then. I think that’s why the clubbing thing meant even more, because it was such a way of escaping pressure, and feeling bonded, and overcoming boundaries that everyone has as a teenager anyway, never mind if you’re in a professional show where you’re judged on your appearance. But I absolutely loved doing the shows. I love dancing and I love traditional Irish music. I love it to the core. I’ve danced since I was five and I will always love it.

There was a combination of reasons why I stopped. Even though I was young, physically it did take its toll. We didn’t even warm up or anything. I’d been dancing on concrete floors in 50p lessons in an old hall, and then suddenly Irish dancing is a profession. So there was no physio – a whole troupe of forty dancers and no physio! Mental! I remember I had a really bad foot because I was putting all of my weight on it, and I remember going to this clinic and this doctor injecting my foot with some herbal nonsense, and my foot went blue. There was that, my eating disorder and really missing home, because suddenly all the music was there. And I really missed green, which is weird because I grew up in Cardiff, which isn’t particularly green. But I missed landscape and… damp. I needed to go home.

In ’98, all of our accommodation was paid for, we got £200 per week PDs [per diems], and we got £1200 per week wages. It was mental. And the reason I say it, is because it didn’t matter. If I’d been wiser, I would have put my head down, done the job and bought ten houses like everyone else did. But what I decided to do was go, “Do you know what, I love music more. I’m really curious and I don’t have a clue what I’m doing, but I just need to be near it.” I think all artists are anarchists, because you get bored and think, “Where is the progress here?

I was on the dole then, and it took fucking years to figure out what I wanted to do, and I’m still figuring it out. I actually did go back and do River Dance for a bit, before I joined The Pipettes. I did that and I got offered the lead role again, and it was at that point that The Pipettes was getting a bit busier, and I was like, “I can either do River Dance and have a steady income or I’ll stick with this indie band from Brighton who are not getting paid for gigs, but actually it’s more exciting. I don’t really know them, but they’re interesting and funny, and where’s this going to go?” Curiosity always gets the better of me.

As told to Stuart Stubbs