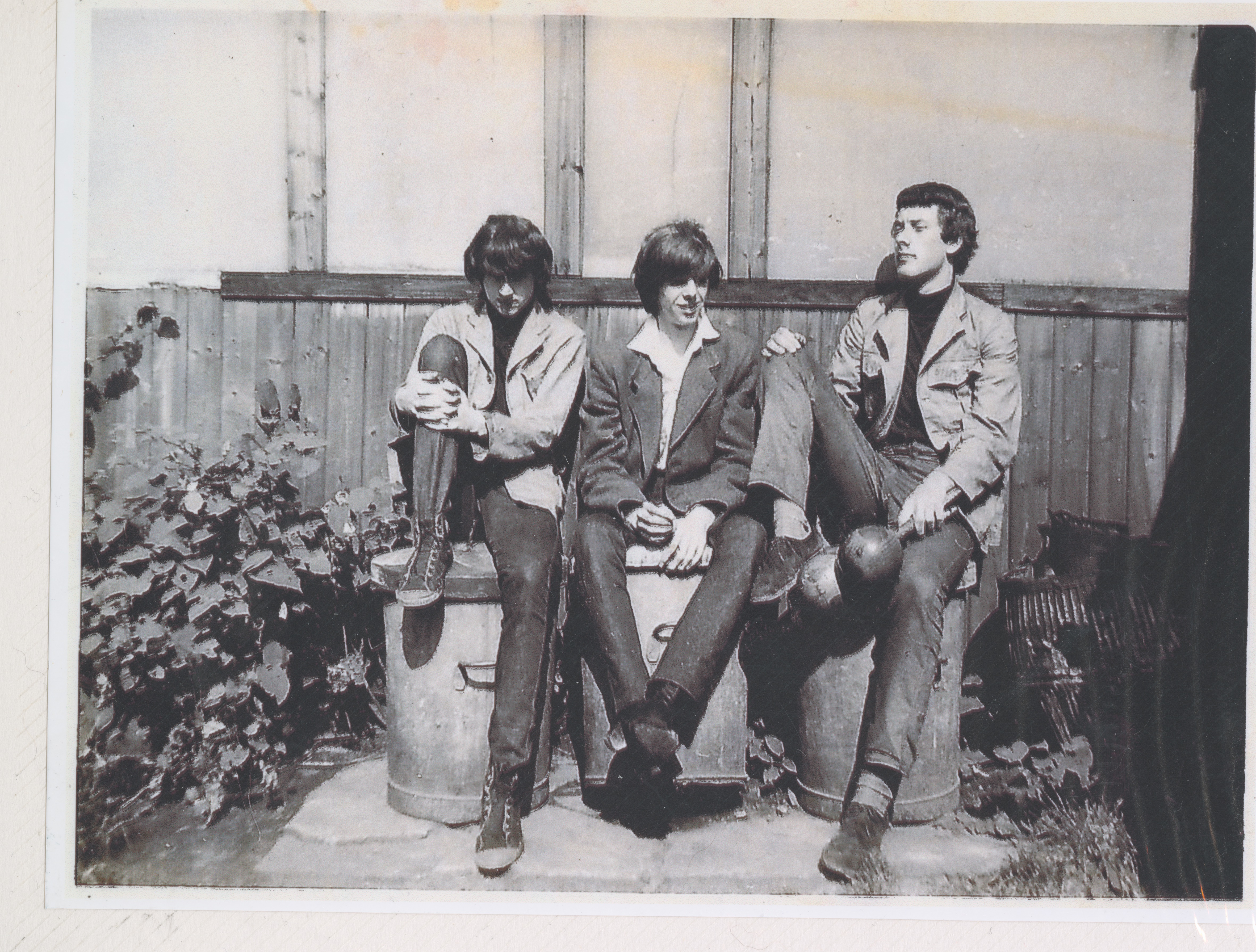

John Cooper Clarke at 16: 1965 really was that good

"It's been downhill all the way" since then, says the legendary punk poet in our latest Sweet 16

John Cooper Clarke [pictured far left]: It would have been 1965. I was in Salford, Manchester. Just left school. It was an important year – I’d just started going into town. I lived very close to the centre of Manchester and me and my pals would walk it in there on a daily basis. We needed to get out of the house in order to swear and smoke cigs, and obviously trying to connect with girls.

I remember ’65 as being a very happy time. I’ve often said that politics has never impinged one iota on the way I live – not a bit except for that one period, that Harold Wilson period. Everyone was happy, it seemed to me. Since then it’s been downhill all the way. Life was improving on a daily basis, and there was no reason to think that this trajectory would ever be abated. Swinging Britain, Mary Quant, mods, Ready Steady Go. Social Mobility – that was the main thing, and it was even obvious while it was happening. It was a really happy time.

I was absolutely determined to become a poet. I’d had enough jobs even by then to realise that it wasn’t my idea of a great life. I’d be sending poems off to publishers, of which there wasn’t many. I thought my poetry was great and there was no reason why somebody shouldn’t publish it and it would sell shit loads of copies. There was no reason for me not to think this. I’m not one of these people that writes poetry for therapy or in the belief that it will make you and everybody that reads it a better person; I’ve always seen poetry as a branch of entertainment.

I got no encouragement in this, of course, from my parents or anybody else – for my own good, they advised me against this course of action, but I was convinced. I was emboldened because there had been renewed interest in poetry because of the career of Muhammad Ali, who we were all very interested in. And I had an inspirational teacher at school called John Malone. It was the only thing I liked at school – I hated the rest of it from the word go.

The first time I read my poetry in public was at a benefit for a left-wing magazine. I was sweet on this beatnik girl and she was performing in an upstairs room in a pub called The Castle, in the Northern Quarter. I told my dad that I’d done this public reading. “Well, anyone will employ you for nothing,” he said. He was anxious that I shouldn’t get mugged off, and it sunk in. I thought, well, who would my dad recognise as a potent symbol of a northern man being successful in the world of show business, and there was one guy I could think of – Bernard Manning, who was mainly known as a club owner then. I thought that would impress my dad, if I could get a couple of quid out of Bernard. So I went to the Embassy Club in the afternoon and Bernard was there. I told him what I did and he said, “They don’t like poetry here, kid. Half of them can’t fucking read.” But I convinced him it wasn’t anything highfalutin by giving him two lines out of a poem I’d just written that I knew he’d like because it was set in a world that he knew, set in a Mecca ballroom: “When the ambulances came, she was lying on the deck, she fell off her stiletto heels and broke her fucking neck.” So he gave me fifteen quid for twenty minutes, which then was a weekly wage for some people. My dad left me to it after that.

As told to Stuart Stubbs