The bloody, brilliant mind of Lou Reed insisted we take the rough with the smooth

Perfectly inconstant: RIP Lou Reed

Perfectly inconstant: RIP Lou Reed

“Lou’s been there all along, from the start” was a text message I got from a close friend when we were in touch the night Lou Reed died. It wasn’t until I really began to dissect that statement that I realised how much truth and power it really contained. I’ve just turned 28 years old and I can’t recall a period in my adult life in which Lou Reed hasn’t factored. When you lose a musical connection that’s entrenched within you, something that’s in your dreams, in your blood and dances throughout some of your greatest living memories, it’s losing more than a person you never met. Such is the stone-faced, misanthropic picture often painted of Lou Reed that any outcry of physical emotion in his leaving this planet almost seems irreverent to such a character. Yet, upon hearing the news, it hit me like a hammer, a short burst of tears and sobbing came from a place I couldn’t explain. But then again, the idea that Reed was a constantly miserable, phlegmatic person throughout his whole life is one that, despite never meeting him, I refuse to buy. My records tell me otherwise, anyway.

I once read a review of Bonnie Prince Billy that attributed his inconsistency as being one of his greatest, most consistent assets. I initially thought it was something of a prosaic cop-out, a miserable excuse to justify an inability to hammer something that probably needed a good booting, but it’s a theory that’s stuck with me over the years, I must admit. I often think it can be applied to Lou Reed. Not because his bad work should necessarily be forgotten or forgiven but because the results of his bad work came from exactly the same place as those that changed the world and split minds open with all the force and shrieking cacophony of ‘Sister Ray’ loaded with an arm full of whizz.

Lou Reed was bloody-minded and hell-bent on his own vision to such a degree that you kind of had to stick with the results. In many ways, if you buckled at the knees when faced with hearing the gut-wrenching beauty of ‘Pale Blue Eyes’, or felt like putting your face clean through the nearest window when exposed to the grinding, antagonistic force of ‘Metal Machine Music’, then you had to trust the judgment that put you in those most polarising of emotional states when subjected to the lacklustre drivel of ‘Original Wrapper’ or ‘Hookywooky’ or yet another rigid, dead-eyed live rendition of ‘Sweet Jane’ sapped of any vivacity. Simply put: you had to do things on Lou’s terms. Incredibly, few artists can boast such a consistency to their approach and dedication to ‘rock as art’, let alone stand behind a body of work so incredibly powerful – for my money, there has never been an artist that could expel a more perfect blend of pop and experimentation than the Velvets did, and nobody could make three chords sound like a symphony quite like Lou Reed.

“There are certain records that are so patently offensive that one wishes to take some kind of physical vengeance on the artists that perpetrate them” is the much quoted 1973 Rolling Stone machete attack on Lou’s glorious ‘Berlin’ LP, but so often this is rolled out as the ultimate insult. In actual fact, it’s the ultimate compliment! The bile, irony-coated pill infinitely sweetened by RS’s (pretty characteristic) back-foot, by subsequently naming it the 344th best album of ALL TIME in a list of 500. On several occasions, with time, Lou Reed’s stubbornness proved to vindicate him. It’s thus utterly bizarre that people would still then criticise him for taking the same approach on future projects.

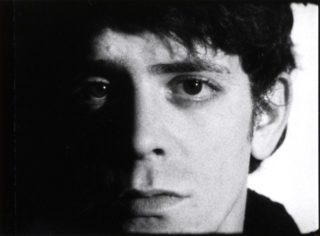

I felt reinvigorated with Reed this year, not because I had felt overly enamoured with his most recent recordings, nor got heavily back into a Lou/Velvets phase, but through his radio show with Hal Willner, ‘New York Shuffle’. It was a show that paid equal homage and disregard to the format of radio – a fitting emblem for Reed’s relationship to rock’n’roll, too, perhaps. It owed a debt to old-time radio of the past, the kind that was eclectic and programmed by the presenter, but it shunned elements of modern day radio. Most notably – and refreshingly – they fundamentally ignored the listener. It was two old timers rambling away to each other, occasionally incoherently, as they picked through each other’s record collections, unearthing a truly heterogeneous selection of music. Aside from the exposure to a dynamic and eclectic playlist, listening to these shows was a great little window into the warm, funny, idiosyncratic side of Reed. He was still occasionally brusque and stubborn but he seemed to have his guard down when removed from the position of discussing his own music (usually the public’s only exposure to him). His voice was a slow, raspy drawl that sounded like rocks being cracked, every bit matching the glorious splintered rivers that ran through his aged face. (I always envisioned Lou getting more and more into W.H Auden territory as he got older).

I perhaps mistook my own reinvigoration in Reed as his own though. Such was my – and perhaps collective ‘our’ – faith in the rigidness of his character that I didn’t bat an eyelid to learn he had had a liver transplant. What, after all, could bring Lou Reed down?