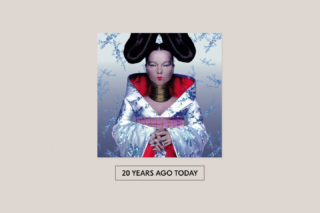

‘Homogenic’ reinvented Björk – it’s still the template for so many other artistic transformations

The next in our series looking at significant albums celebrating their 20th anniversaries in 2017 reaches Björk's landmark third album

The next in our series looking at significant albums celebrating their 20th anniversaries in 2017 reaches Björk's landmark third album

Last Friday, Björk gave a live online video interview to discuss her forthcoming album. For fifty minutes, she sat in a badly lit hotel suite and talked with unflinching sincerity about collaborating with cutting-edge film directors, confrontational music producers and high-concept fashion designers, all of which would resemble fairly ordinary promo fare had her face not also been obscured throughout by a giant lily perched on the end of her nose.

Tellingly, the headgear was barely mentioned, the implication being that this style of presentation, eccentric though it may be, is simply par for Björk in 2017, as unremarkable as, say, a rapper in a baseball cap. That seems about right, too: no longer just an offbeat pop star, Björk is these days a sort of experimental multimedia node programmed to provoke, whose musical output runs parallel to virtual reality experiences, interactive apps and retrospectives at the New York Museum of Modern Art. For modernday Björk, the idea of turning up to an interview with a flower over your face is, if not exactly expected, then at least typical.

Things were different in 1996, though. Björk was at the apex of her musical popularity following the triumph of big-band jazz confection ‘It’s Oh So Quiet’ and the ensuing masterful genre patchwork splatter of her second album ‘Post’. However, the attention both from gossip columns and from one tragically ardent fan had become so discomforting that change was urgently required. Her subsequent transition over two decades, from quirky pop pixie patronised by the tabloids as a novelty weirdo to serious tastemaker sporting entirely standard facial foliage in public, is unique. It’s one that has shaped both Björk herself and the work of her peers, and it’s also one that, publicly at least, began twenty years ago today with the release of ‘Homogenic’.

There can’t be many albums more resolutely alien as ‘Homogenic’ that still manage to squarely occupy familiar pop territory. Equally, it’s difficult to recall another record that’s so clearly chiselled from a single piece of stone but which simultaneously feels so modular. But such are the gleeful contradictions of ‘Homogenic’: its cold electronica retains a melancholy warmth, and there’s a sort of warping density to it even at its crystalline sparsest, like staring through metres of flawlessly transparent reinforced glass. All of that seems satisfyingly deliberate, too: Björk’s reported desire was that ‘Homogenic’’s front cover depict “a warrior who fights not with weapons but with love” – the sense here is of someone rather revelling in all their assembled incongruity.

Despite that, though, perhaps the album’s most enduring virtue is its almost symphonic focus. Gone is the playful genre-hopping of ‘Post’ and ‘Debut’, instead replaced by a steely single vision in bellicose rhythm and sweeping string arrangement, the kind of music with which Björk could send her warrior cover stars off on their crusade. “I’m going hunting!” declares the album’s opener, it’s accompanying video portraying Björk being overcome by increasingly complex digital armour, in a neat allegory for the album’s tone; at the album’s other end, ‘Pluto’ finds Björk at her most aggressively euphoric, before the closing ‘All Is Full Of Love’, hypnotically depthless and almost ritualistic, summarises her manifesto.

Indeed ‘Homogenic’ finds Björk waging a kind of campaign of love throughout, albeit not for a specific other person but more for everything, and for the electricity of just being alive. “You can’t say no to happiness”, she yells during ‘Alarm Call’, one of the album’s most direct moments. Elsewhere that electricity manifests itself in a desire for unbridled intensity, for a sort of cybernetic rapture: “excuse me but I just have to explode!” announces ‘Pluto’, “a state of emergency is where I want to be,” attests ‘Jòga’, while on ‘Bachelorette’ Björk produces perhaps the most self-assured, elemental image of the entire record: “I’m a fountain of blood in the shape of a girl”, she sings, sculpting herself in the very essence of life, as unassailable strings swell beneath.

Then again, in yet a further contradiction, that focus on self-actualisation is repeatedly disrupted, with Björk turning momentarily bashful and chastising herself on both ‘Immature’ (“How extremely lazy of me!”) and ‘Hunter’ (“How Scandinavian of me!”). It complicates ‘Homogenic’, sure, but for the better: the result is an album with startling three-dimensionality – honest, human, nuanced – which, along with similarly textured music, is surely why the album still sounds so arresting after twenty years.

Björk would go on to make even denser records – in particular, ‘Medúlla’, constructed only by voices, and the techno-naturalist statement of ‘Biophilia’ remain foreboding monoliths in her catalogue – but nonetheless, one can trace all of her subsequent music back to ‘Homogenic’. Its single-issue sense of intent marked a decisive, successful development, and that thematic focus, alongside the album’s fearless emotional sensitivity and technical meticulousness, has since become quintessentially Björkian, whether it’s manifested in the sensuous euphoria of ‘Vespertine’ or in ‘Vulnicura’’s exposed heartache.

That foundation-building quality alone is enough to make ‘Homogenic’ Björk’s most important album. However, revisiting the album twenty years on, it’s unavoidable how much it also resembles a modern template for successful artistic reinvention more generally. The internal paradoxes of Kanye West’s ‘808s And Heartbreak’, for example, seem to echo those on ‘Homogenic’; even more pertinently, it’s almost uncanny how much ‘Homogenic’ presages perhaps the single most radical departure of any band in the past twenty years, that of Radiohead with ‘Kid A’. In its approach and inspiration, its execution and particularly its shape – from brooding opener to lightly ambient mid-album interlude to beatific and shimmering harp-laden finale – Radiohead’s fourth record corresponds eerily with Björk’s third. Even more impressive for ‘Homogenic’, the fact that Thom Yorke has subsequently cited ‘Unravel’ as his favourite ever song suggests that those similarities are not entirely coincidental.

It’s quite the legacy. To change one’s own creative path is important, but to make ripples that clearly affect others of such standing suggests influence on top. A year before all this, Björk’s inescapable tagline had been “shh”. After ‘Homogenic’, she didn’t need to tell anyone to shut up.

Also out this week in 1997:

Stereolab – Dots & Loops (Duophonic UHF), chart peak #19

Finley Quaye – Maverick A Strike (Epic), chart peak #3

Dubstar – Goodbye (Food), chart peak #18

To read all the other entries in Sam’s Twenty Years Ago Today blog, click here.