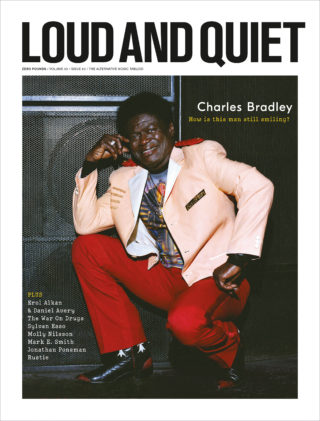

A year on from his death, Charles Bradley still embodies hope in the face of adversity

A world that could do with his message of love, hope, perseverance, positivity and peace

A world that could do with his message of love, hope, perseverance, positivity and peace

When Charles Bradley “the screaming eagle of soul” passed away in September 2017 of stomach cancer he was 68 years old. He had released three albums in his lifetime, all of them in his sixties. This month (November) he would have turned 70. His final – posthumous – album, ‘Black Velvet’, came out the same time.

During a period of what feels like unprecedented turbulence in the world, as we seemingly plunge deeper and deeper into chaos, division and inevitable environmental collapse, it can become difficult to latch onto moments of unadulterated joy and escapism. Unplugging yourself from the world becomes harder and harder as it spins around with such dizzying pace it creates a sense of perma-nausea. It’s led me to think about Charles Bradley a lot recently and about his ability to turn pain of excruciating proportions into moments of overpowering beauty and flooding catharsis. And how much I miss it.

Charles had an extraordinarily difficult life (which we covered in detail in our 2014 cover feature with him) that involved homelessness, jail, a lot of death, pain and suffering and a deeply buried musical talent that wasn’t truly presented to the world until his was in the final stretch of his life. Yet the six years he got being able to be a full-time touring and recording artist he used as a giant connecter between audience and performer to inject a mainline hit of love, hope, peace and equality.

Thank you, Arcade Fire

The first time I saw Charles Bradley was at Primavera Sound in Barcelona in 2014. As people flocked in the tens of thousands to watch Arcade Fire, a small cluster of friends and I wandered aimlessly for an alternative when we walked past the stage Bradley was playing on. I heard this yelp that cut through me like a jolt of electricity. Turning to the stage I saw an elderly man in a jumpsuit with a little potbelly, spinning and dancing and gyrating. His band were flush-tight, locked into a soul-pop groove, all dancing bass lines and tooting brass as Bradley unleashed flooring vocal take after flooring vocal take. It was like watching someone pull out every single ounce of themself until there was nothing left to give. It was an exorcism of sorts, yet one you could dance to.

This wasn’t a one-off special performance however. This was the go-to performance mentality for Bradley. I would see him another three or four times over the next couple of years and it was the same every time. He would be the artist I would drag people to see at festivals regardless of their tastes. His records were great, and some tracks were knock-you-on-your-arse brilliant, but nothing could capture the magic, guts and raging emotion of his live performances. He was a furiously boiling pan of torment that was always ready to boil over, and his performances were such a furious catharsis of melancholy and beauty that they never lost their potency – he was like a sadness well that refilled itself.

Taking your misery and dancing to it

Bradley had built up a lifetime of so much pain, death and anguish that he could endlessly tap into it night after night and deliver it with nuance, blending joy and despair. Like all the best soul music it was taking your misery and dancing to it. I cried at every single one of his shows. He was capable of reaching into something so deep inside of himself – or perhaps his emotion was always so close to the surface – even just to watch him felt like a purge of sorts; a man shedding something, stripping away a layer. Even when covering Black Sabbath’s ‘Changes’ he was able to stamp his own story to it so firmly that when he would rip open his heart and lungs to scream “I’m going through changes” every word felt like it belonged to him.

The opening lines of “I feel unhappy, I feel so sad/ I’ve lost the best friend that I ever had/ She was my woman/ I loved her so” were almost predestined to be sung by Bradley, especially so shortly after the death of his mother, who had been his literal best friend. Look at clips of him performing that song, pick any from across a few years from anywhere in the world, and he never performed that song in any way other than looking like he was about to burst. Never so much as a glimpse of insouciance crept into his delivery.

Seeing him live became like being part of a club. If you met someone who had also seen him you’d immediately be able to communicate the feeling without words, like a sly wink or intricate handshake between a select few. Everybody I took to a show was floored. I remember dragging along someone who I had just met at SXSW in 2016, who worked at Warp Records and ran his own grime label (hardly an artists sketch of your typical fan of overly-intense and emotional classic soul). Yet I watched him look on, glide into the groove with the band and saw the silence wash over him. His jaw began to sag and droop before dropping entirely when Bradley would hit one of those big lung-busting moments.

You’d then witness the connection people would have with the still palpable sense of suffering that Bradley possessed during songs such as ‘Heartache and Pain’ when he would cry “your brother is gone” as he retold the story of coming home to find the murder scene of his own brother.

Yet one of the many profound beauties to be plucked from the music of Charles Bradley was not wallowing in the misery of it or voyeuristically lapping up the pain of a man. These instances were delivered with a pronounced belief in love and sharing; it was Bradley’s way of connecting with a world that he had fundamentally been disconnected from for so long. He had every right to be a bitter and choleric man. He was abandoned and homeless as a child, left to sleep on subway benches and live amongst drugs and crime and violence, only to later take on the role of full-time carer for the same parent that was once unable to look after him. He grew up to be illiterate, working bit jobs and moonlighting as a James Brown impersonator in the evening. He nearly died from being given penicillin and then watched his brother die on his doorstep, before seeing his mother and uncle pass too. He lived in a crime-ridden neighbourhood with bullet holes in the wall and yet all the pain and suffering and difficulty was not soaked up and expelled as anger and resentment. It was re-focused as positivity, hope and love. Bradley would profess peace, spirituality and equality at his shows, physically connecting with the audience in a voyage of unity.

Why was is to hard?

Bradley was almost childlike in his wonder of the world at times and the connection his music made across continents. There’s a scene in the 2012 documentary on his life, Soul of America, in which he goes out to pick up a copy of the New York Post to find himself in it and he’s so filled with unbridled joy he is bursting with exhilaration. He stops the nearby postman walking past to show him, he stops passers by and locals he knows in the streets who hug him in return. It’s a moment that is a distillation of profound and truly pure beauty and humanity that Bradley himself managed to recreate through his music and performances.

His tale could be construed as something resembling the American Dream, a tale of someone who has experienced homelessness, jail, death, pain and isolation and managed to turn it all around and make it in the world of music. But too often these stories that are hooked on ‘making the dream’ ignore the living nightmare some people are expected to live through in order to find a modicum of happiness. If Bradley’s story is one of what is possible in America, then it’s one that highlights how much unrelenting suffering one person can go through with little support and assistance as much as what they are still able to achieve with some luck and unwavering belief.

On the 2011 track ‘Why Is It So Hard’, Bradley sang the refrain “Why is it so hard to make it in America?” before wrapping up the song by declaring, “We gotta make a change in America.” Sadly, this sentiment is now truer than ever and it’s a deep shame and great loss that an artist so rooted in the possibilities of love, hope, perseverance, positivity and peace is no longer around to help lend his voice to make such changes possible. A year after his death, he’d probably have something more positive to say on the matter. Indeed, we were lucky to have found him at all, eventually.

Photos by: Issac Sterling / Gabriel Green / Press