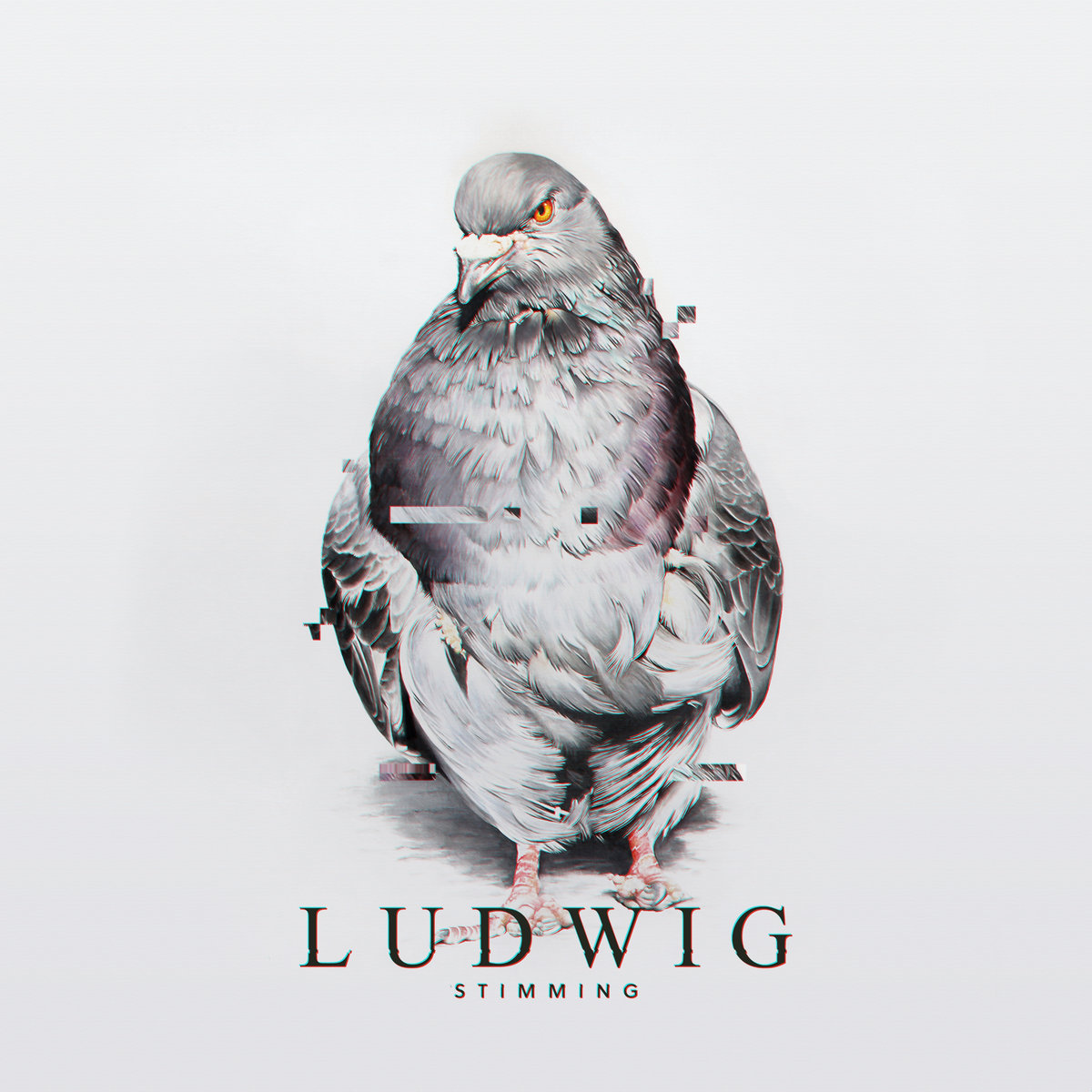

Stimming Ludwig

Hamburg producer Stimming has always known what his music was for. He made his name in the competitive world of the heavyweight techno clubs of his homeland and rarely has the function of music ever been more clearly defined than it is there. But in the afterglow of his 2016 album Alpe Lusia, he started to grow uneasy. What if he were able to strip away the central tenet of club music? What would remain? Is there even such a thing as beat-less techno?

Ludwig is the result, an album that is difficult to qualify but endlessly fascinating to consider. There is tension in these recordings. From its very title, which appears to invoke the name of the legendary drumkit brand as much as any vaulted Teutonic musical demigod, we are presented with contradictions: we very rarely are able to distinguish live organic percussion on Ludwig, but rather are presented with a hybridised, digitally-embedded new reality. There is nostalgia tied up with the Ludwig name that matches our craving for something real and handheld, but instead Stimming presents us with a different truth.

We are not ourselves machines but we are no longer able to be free from them either. There is danger in our reliance on technology – both a terrifying physical threat and a more insidious psychological peril – and this record seems acutely aware of it. We all know it really, but few of us make the choices necessary to protect ourselves from it and tracks like ‘9PM’ present the digital/organic interface as something menacing. From the opening strains of ‘Intro’, warm piano keys stand defiant in the face of sharp, serrated static scuzzes; it is a recipe for disaster, like a discharge of electronic energy near a waterfall.

At other times, Stimming appears more optimistic about the combination, as on ‘Circle of Thirds’, with its playful, interlocking synth lines diving in and out of step with one another with almost comic panache. Beats occasionally attempt to wriggle free, as on ‘Judith Maria’, but Stimming ultimately chooses restraint and where momentum is denied, melody slowly begins to emerge. That track, like many others, is understated and quietly rather beautiful. Such intricate compositional details and sonic paraphernalia are not new to Stimming’s work, but they have been set free here and allowed their one glorious moment in the spotlight.

For ‘The Hyve’, Stimming placed a recorder inside a real beehive overnight, capturing the sound of one of nature’s most advanced organic wonders, as good an example of evolution creating its own technology as real life can provide. Perhaps in these inner workings of a sophisticated, quasi-socialist society, we could find the answers we crave.