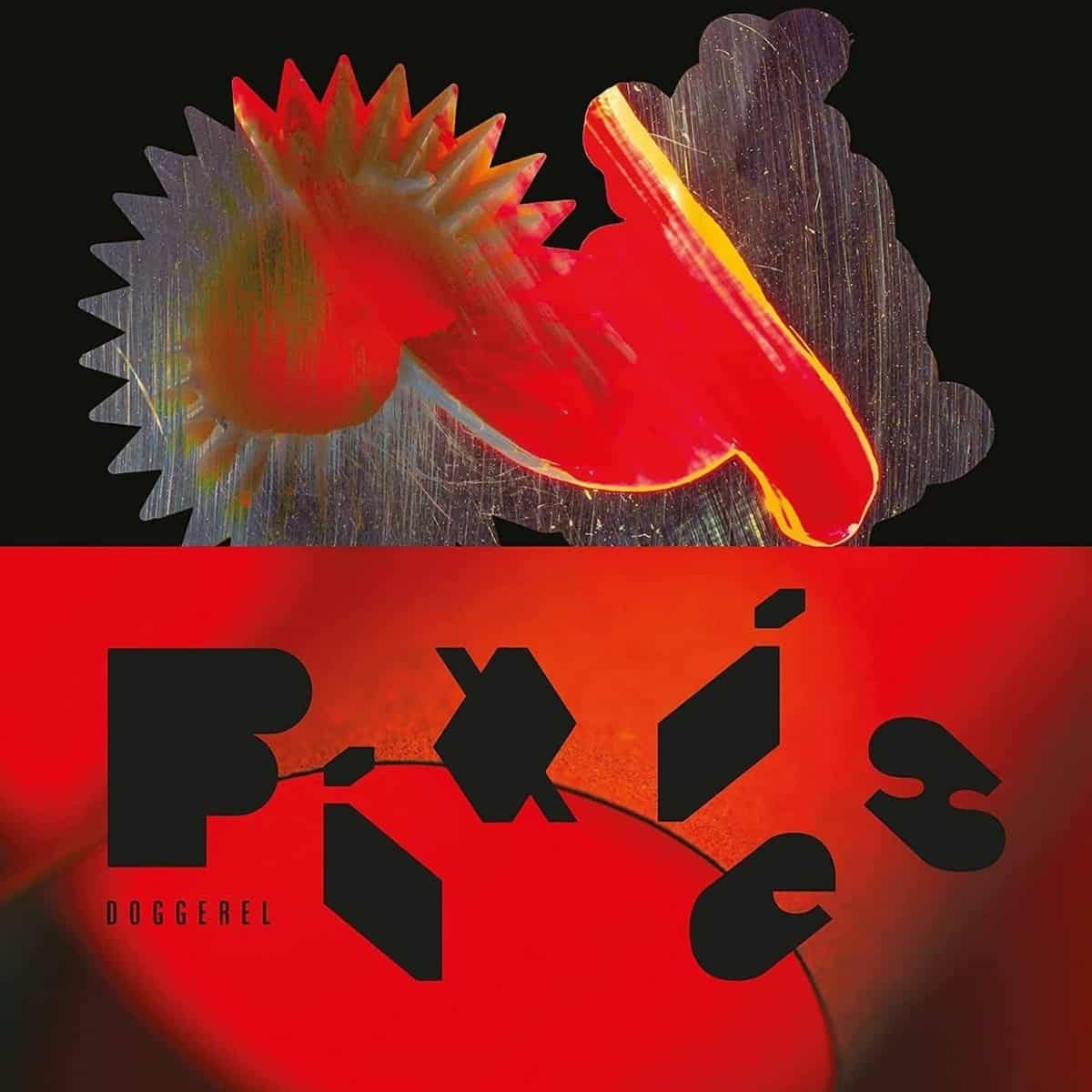

Pixies – Doggerel

In the press release for Pixies’ new record Doggerel, the band’s inimitable vocalist/guitarist Black Francis is quite clear on the direction intended with the album. “We’re trying to do things that are very big and bold and orchestrated,” he said. “The punky stuff, I really like playing it but you just cannot artificially create that shit. There’s another way to do this, there’s other things we can do with this extra special energy that we’re encountering.”

Given Pixies’ output since their reformation in 2004, Francis’ words hardly instil much optimism. 2014’s Indie Cindy was an absence of ideas, a numbing disappointment that, even with the 21-year lag since they initially broke up in 1993, felt disorientating given the calibre of their work during phase one. Head Carrier (2016) was a little better, and so again was Beneath the Eyrie in 2019, Pixies’ last release ahead of Doggerel. Perhaps it was the growing influence of bassist Paz Lenchantin, who, having joined for Head Carrier, undoubtedly brought a freshness and a rejuvenated energy to what was, sadly, becoming a tired outfit. The record even contained a few bangers, most notably ‘On Graveyard Hill’, a rare occasion in the past few years where Pixies have managed to bridge the gap between where they were, and where they want to be.

So given how tepidly attempts at experimentation and reimagining their sound has gone so far, it’s fair to say that Doggerel didn’t land with the expectation typically associated with one of the most influential alternative bands of the late 1980s and early ’90s. The first thing to say, then, is that this is the best Pixies record since they’ve reformed. Across Doggerel’s 12 tracks, Francis and co. rip through a range of styles, from furious grunge to acoustic pop swoons, often, if not always, with a gusto that on occasions almost gets you feeling excited again. You could describe some of it, even, as big, bold and orchestrated.

Things kick off simply enough with the punchy ‘Nomatterday’. While hardly the band’s most impactful album opening track, its lack of frills and strong-enough chorus make for a decent start. Elsewhere, the titular song pairs a spaced, desert-rock vibe with some cookie-cutter, if nonetheless oddly entertaining, notions of a life of nomadic wanderings (“On the road to somewhere, on the road to nowhere / It’s the same to me”). The song also gives guitarist Joey Santiago one of his first two Pixies songwriting credits, contributing the lyrics, while also writing the music for the excellent ‘Dregs of the Wine’. Alongside tracks such as the tender folk piece ‘Who’s More Sorry Now?’, there is a distinct impression that Pixies are displaying an intention to continue searching for a new space to belong.

As was the case on previous releases, such as the aforementioned ‘On Graveyard Hill’, some of the best moments on Doggerel however come when the band continues to draw on their mighty back catalogue, while retaining their presence firmly in the present. Most notable here is ‘Get Simulated’, an absolute ripper of a tune on which Francis’ largely restrained vocal performance is matched effectively with instrumentation similarly paired-back and considered. Continually threatening to burst from its meticulous, contained structure, it never does, leaving its listeners desperate for more without feeling at all stood up.

But this wouldn’t be a typical post-reformation Pixies record if it represented a totally smooth transition into whatever it is the band are now aiming for. ‘Vault of Heaven’ struggles to get out of first gear, as both the storytelling and the performances languish and falter with little aplomb. ‘You’re Such a Sadducee’ is the worst thing here, if just for Francis’ offensive rhyming of “sadducee” with “sad to see”. Attempting to be disarming and irreverent, it instead feels contrived and performative, and very much not in keeping with what, at times, makes Doggerel tick.

Given their recent run, the prospect of a new Pixies record that could be worth more than a handful of listens seemed fantastical. Beneath the Eyrie may have felt like a step forward, though context is key; if stood up against much of their earlier work, there’s no real comparison to be made. While still failing to scale the unassailable heights weary fans yearn to believe the band are still capable of reaching, Doggerel does restore some credibility to the idea that Pixies aren’t just worth seeing for their back catalogue. Though far from the end product, it does do that one thing which for a few years it was feared may not have been possible – it instils hope. Hope that, perhaps, this band has some future yet.