Oneohtrix Point Never Age Of

Maybe it’s just Kanye’s recent Twitter comeback (like a bull returning to the china shop post-refurb), but it seems ‘genius’ is back up on the sparring agenda lately. Maybe those questions never really left the arena of popular culture; is genius real and measurable? Can it be excused for unfavourable or unacceptable behaviour? Equally loved and detested, is genius inherently provocative – a name ascribed to star-children overseeing all humanity, reflecting both good and ill? Does genius perennially exist against the grain?

If we’re to take these running definitions, one such figure that comes to mind is Daniel Lopatin – or Oneohtrix Point Never, as he is professionally known. His recent output on Warp Records seems to render into noise the tension between living online and living IRL. It bustles like a busy Internet forum, pushed to depletion with memes and ripped horror soundtracks. As such, his mercurial style brushes culture both high and low. Think of the brazen emoji-drama of the ‘Boring Angel’ music video, or the prestige lo-fi mini-epic directed by Jon Rafman as visual accompaniment to ‘Sticky Drama’. Like Brian Eno’s landmark ambient works, Lopatin similarly draws from a utilitarian strain – not music for airports, but for the shopping galleries of our capitalist dystopia. He explores cultural memory and hidden utopianism within MIDI instrumentation (objects once marketed practically as toys) and the heightened, angsty break-up pop of the early-to-mid-2000s, as evinced in the samples of his Chuck Person project, believed to have singularly spawned the Vaporwave genre.

This is largely what crystallises Lopatin’s status as the embarrassment of electronic music, being as he is a child of the American ‘prosumer’ boom, a lineage echoed in the ease of uploading your drone album to Bandcamp for all the world to hear. It’s Lopatin’s amateurism that sets him apart from the meticulous footwork of Jlin and the lithe electronica of Holly Herndon. It wouldn’t be too big of an exaggeration to cast him as the typical figure of white, male mediocrity, unremarkable in comparison but inexplicably more popular and successful.

Anyone casually lurking might call him a hack – albeit one with a good work ethic (his latest release is something like his 15th overall, discounting last year’s Good Time film score and countless other extra-curricular activities). Genius, for what it’s worth, is usually coterminous with what some might consider disgrace, and OPN – genius or not – is one of today’s great musical disgraces. Like other artists with unending inventories of main releases, documents, and other ephemera (Nurse With Wound, John Coltrane, Merzbow), OPN makes a point to stay busy. What’s more, his audience follows regardless.

Just like label mates Aphex Twin and Autechre, you’re typically left exhausted by an album’s end. The music itself sounds fatigued, worn thin by the elements. A cult figure among the YouTube generation, Lopatin’s erratic style – from pulsing electronica to new age serenity within moments, sometimes simultaneously – imitates the velocity and vulgarity of a 30-minute Vine compilation. Repeated listens of his latest offering ‘Age Of’ has a similarly numbing effect. The whole world and all of history physically passes by– yelling, caressing, judging, pummelling, hand-shaking – in much the super-accelerated fashion at which the age of information seems to be travelling.

It’s all part and parcel to one of Lopatin’s influences this time around – the Cybernetic Culture Research Unit (Ccru), an accelerationist collective established at the University of Warwick by philosophers Sadie Plant and Nick Land. Accelerationist thought is suitably pulp-post-apocalyptic; it revels in capitalism’s rolling negation, interested in strategically hastening into chaos, faithful in an eventual collapse.

Lopatin’s vision has always been one of eternity. But whereas the drones of 2010’s ‘Returnal’ gestured at eternal return, an unbroken plane ending where it started, his recent work, ‘Age Of’ included, moves outward in multiple directions. It’s near-impossible to follow upon first listen, a choose your own adventure book in which threads are discarded and picked up later or sidelined altogether. These inscrutable structures and jarring sounds (see ‘Warning’ for an actual headphone jump-scare) send the listener falling through different planes and dimensions. It’s transcendental experience mixed with boredom, like staying up late with a friend, channel-hopping the premium Sky package. You get brief glimpses into infinite worlds and possibilities, but they’re evaporated before any context reveals itself.

It’s no surprise that ‘Age Of’, especially its latter half, is occasionally cabalistic, and frequently unlikable. But despite its spots of inscrutability, it may be his most accessible release yet, if perhaps not by his own hand. The surprisingly conventional, groove-lead structures of ‘Black Snow’ and ‘The Station’, accompanied by auto-tuned vocals, bear the stylistic tells of Lopatin’s collaborators. There’s James Blake’s lopsided pop song-craft, and ANOHNI’s seraphic vocals on ‘Same’ and ‘Still Stuff That Doesn’t Happen’ feel generous and open-armed, even as she mournfully sings something that sounds like “into dust, into dust”.

Oddly enough, through the mess of stimulants, I think of another disgrace of popular music. Progressive rock traded in overabundance – of pretence and muso tendencies – leaning as it did toward the dead cult of the saturnine composer genius, away from the ‘fair game’ ruckus of punk rock. Stranger still, OPN seems to want to revive the genius figure for a style of music theoretically founded on a level playing field.

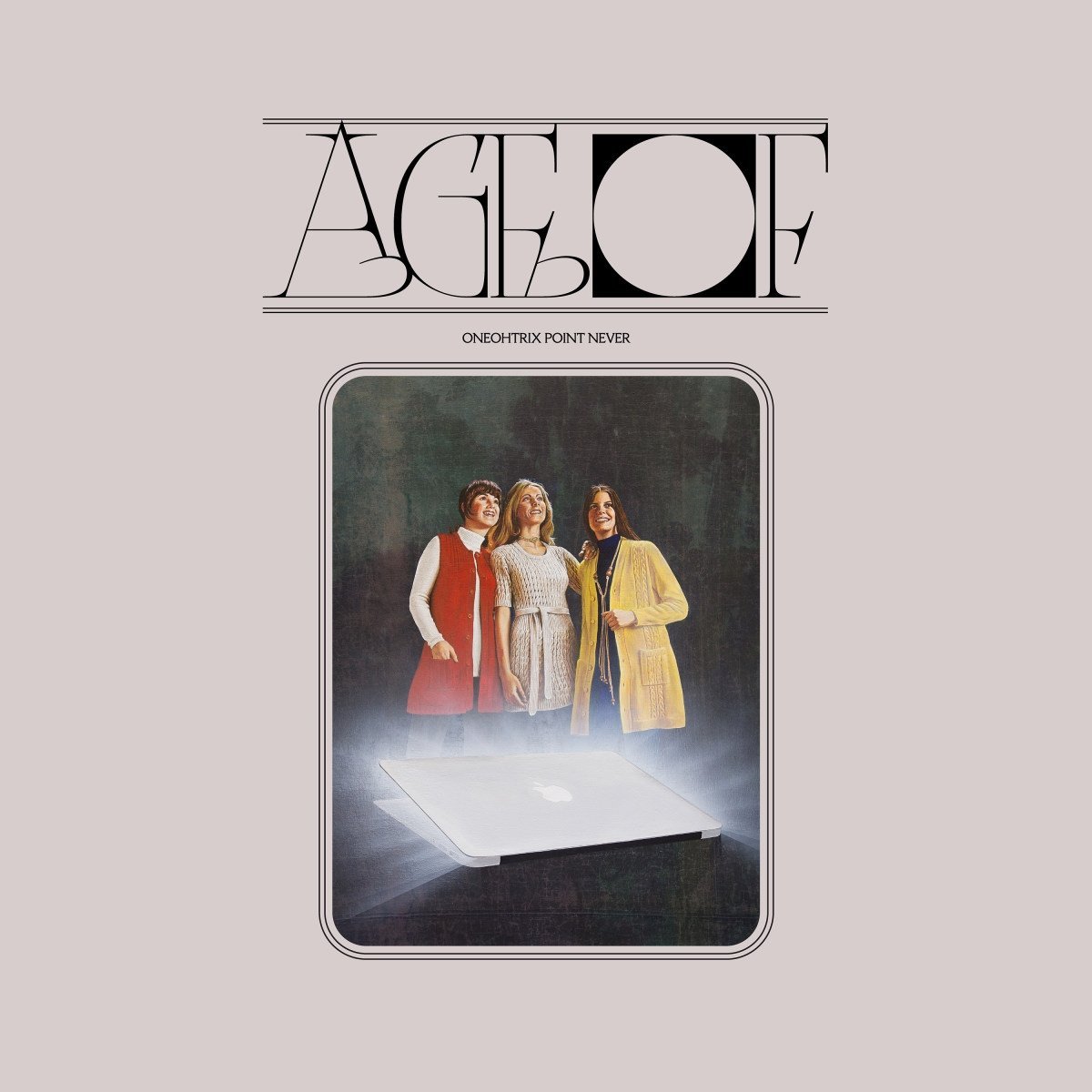

“‘Age Of’ what?”, we might ask. Ecco, Harvest, Excess and Bondage, if we’re to believe the press material. More concretely however, a lot of the album’s mystique draws from Baroque and Renaissance thought. Firstly, there’s the predictably anachronistic metaphor of the four François Desprez engravings, lifted from a 1565 set translated as The Droll Dreams of Pantegruel. They depict grotesque human-animal-object hybrids, nightmarish renderings of typical folks from Desprez’s France; warriors with fire bellows for limbs, dignitaries with long, drooping noses. We already know what Lopatin wants us to think. “Are we not like these engravings?!” he asks, “misshapen cybernetic amalgams, with our electronic devices as prosthetic fixtures and our curated half-selves in cyberspace?” We should have known that this OPN release would be his least subtle; there’s a MacBook right there on the cover.

The album teaser boasted the incongruous harpsichord phrases we’d later hear throughout the album (the title track, ‘myriad.industries’) bringing to mind the cult of the musician genius J. S. Bach. As we know, OPN is only really able to accommodate a risky kitsch tonality ironically, so here the harpsichord phrasing stands as shorthand for “old timey”, like the opening music of an establishing shot for a Looney Tunes cartoon. Or so it would appear.

The music video for ‘Black Snow’, directed by Lopatin, features some more confounding imagery, centrally a red devil dressed sequentially in a hazmat suit, then a dignitary’s white wig, recalling the painted image of Bach now synonymous with the man. He composes at his computer, gesturing towards a framed picture of the earth, the subject of his composition. “The Devil is playing the world…” reads one YouTube comment, which is correct in a few senses. Later in the video, the devil literally ‘plays’ the framed earth with a bow. He also tricks the world à la René Descartes’ sense-confounding malicious demon, via the grandest illusion in history: music. By now you may be thinking of Trump, fake news, and the rise of far-right populism. This is undoubtedly deliberate.

Regardless, the Renaissance in Europe, exulted by scientific observation and empiricism, prefigured the decline of religion as a defining narrative. The anachronistic ‘Age Of’ demands that we too become weary of grand narratives, or ideologies, as they are sometimes called.

Still, something troubles me. Is Lopatin casting himself as a new leader of a genius cult, or could he be exposing genius as a grand narrative of popular culture, the old guard yet to be toppled? Or is all this undue credit? While some might consider him a rascal genius, I’m happier just settling for the former.