Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds Ghosteen

The 2016 documentary One More Time With Feeling is, first and foremost, a film about a person getting back to work after an event of unimaginable trauma. In this case, that person is Nick Cave, the work is the recording of the album ‘Skeleton Tree’, and the event of unimaginable trauma is the horrific accidental death of Cave’s 15-year-old son Arthur in July 2015. “It was not an act of courage or anything” Cave later told the journalist Chris Heath, “it was just that I didn’t know what the fuck else to be doing. All I knew is that what I do is work, and that kind of continues. I think I knew, fundamentally, that if I lay down, I would never get up again.” Throughout his career, and certainly since he quit drugs in the late 1990s, Cave has got up five days a week, put on a suit, headed to the office and worked.

Something else, though, was going on with One More Time with Feeling. Why did he put himself through the experience of having the director Andrew Dominik document the very worst time of his life? Some suspected a ruse to avoid promotional interviews – this is folly, had Cave retreated from interviews for the rest of his life, absolutely everyone would have understood. No, something in Cave as a person – and as an artist – was changing, and it manifested itself in an urge to share and a compulsion towards the communal. To change in significant ways is not an uncommon reaction to grief and trauma, and Cave has been lucid about the “elastic band” or trauma, continually binding him and his family to that atrocious day in 2015. The film was the first sign of this change, and the second was the tour that followed Skeleton Tree. Watching those shows, the provocation towards the audience that typified Cave’s performing career became something else entirely – combativeness melted into communion. This continued with the launch of the Red Hand Files – a mailing list in which fans send questions to Cave and Cave selects those he wishes to answer (with answers ranging from the flippant to the forensic and heartbreaking). And then too, across 2018 and 2019, we had the ‘Conversations with Nick Cave’ events where fans were encouraged to, in Cave’s words, “ask me anything.” “Nothing can go wrong” Cave observed of the high-wire spontaneity of those fan events, “because everything has gone wrong.”

And so, announced via the Red Hand Files just a fortnight before release, we have Ghosteen, a double album. Cave has gone back to the office, he’s put the suit back on, and he’s knuckled down – recording the album across last year and this in Los Angeles, Brighton and Berlin. “The songs on the first album are the children” explained Cave in the album’s promotional materials, “the songs on the second album are their parents”. The two albums are stylistically distinct – the first are songs, the second are spoken-word poems over electronica soundscapes – but I don’t think that’s what Cave means when he refers to the ‘children’ and ‘parent’ relationship. We’ve no idea of course, but given that the same image of Jesus lying in his mother’s arms reoccurs on both of the albums would suggest the poems acting as creative spur for the songs.

For obvious and understandable reasons, the extent to which Skeleton Tree represented a stylistic break with Cave’s back catalogue went underdiscussed – it sounded like a creative breakthrough, and on the evidence of Ghosteen Cave is treating it as exactly that. Why was that record such a stylistic departure from the Bad Seeds’ previous work? For one thing, Warren Ellis’ electronics that had crept into 2013’s stunning Push the Sky Away were suddenly front and centre – the main meal. Similarly, Cave’s lyrics deviated heavily from his traditional maximalist Southern gothic conquests. In their place came something more elliptical, closer to modernist writing in their fragmentation and eschewing of narrative. It’s testament to Cave’s pedigree and discipline as a writer that he can flit from one mode to the other and produce work of such quality (that’s what you get for heading to the office every day).

At times, Ghosteen appears almost in dialogue with its predecessor, and this is no bad thing. Opener ‘Spinning Song’ seems to have itself spun from a line on Skeleton Tree – “the song, the song, the song it spins since nineteen eighty-four.” The gorgeous, revelatory Ellis backing vocals seen on ‘Girl in Amber’ are replicated all across this album, to beautiful effect.

As the vast bulk of Skeleton Tree was written prior to Cave’s tragic loss, it’s on Ghosteen that we have the first real document of Cave the writer working through pain and grief. There’s an embarrassment of riches here, and emotional gut punches land hard and fast from the outset. He writes on ‘Sun Forest’ of “a man mad with grief”, of “everybody hanging from a tree” – it’s an astonishingly vivid portrait of the fever that grief can be. I don’t often cry at music – just one of those things, doesn’t seem to happen – but on two separate occasions, at two different points on the record, I found myself in tears. Filling the void of loss and of grief is, though, nothing new in Cave’s work. Cave’s father, who introduced him to literature, died when Cave was just nineteen. “I see that my artistic life” he explained in 2001 “has centered around an attempt to articulate an almost palpable sense of loss which laid claim to my life.” I’ve long agreed with the writer John Doran’s point that a helpful way to understand Cave’s writing is to “picture a youngish Nick Cave unable to subdue the voice of his beloved father…asking ‘is this really good enough Nick?’”

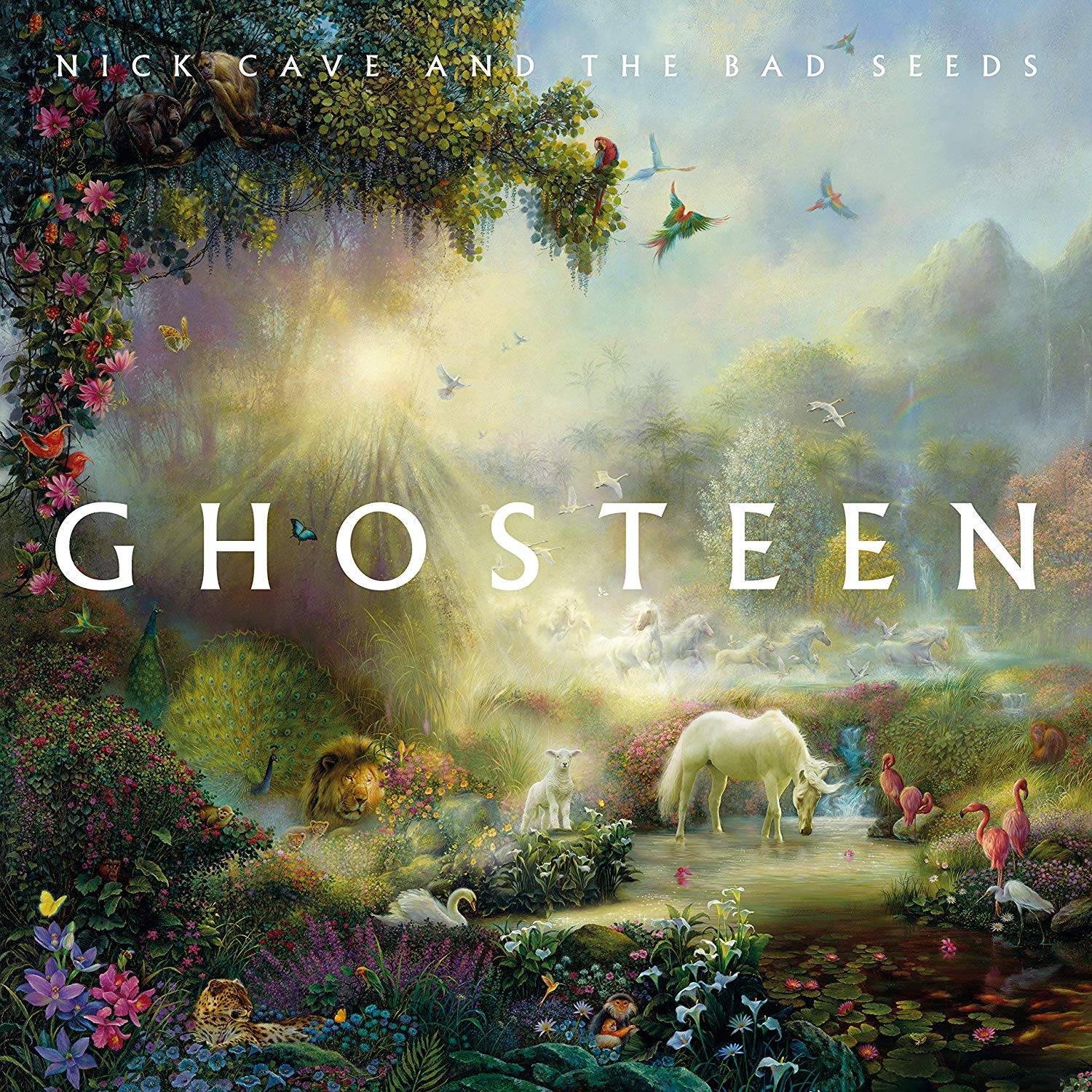

Writing in the Red Hand Files, Cave explained that following Arthur’s passing, “we all needed to draw ourselves back to a state of wonder. My way was to write myself there.” Ghosteen begins to make much more sense in this context – the lyrics are dense with imagination. Cave as fantasy writer, striving for the victory of wonder and the imagination over the horror of things as they are. This fits, too, with the album’s artwork resembling something from blockbuster fantasy cinema – mythology and kitsch in blinding technicolor. The most striking expression of Cave’s push towards wonder is the recurrent motif of horses (also present on the artwork). Horses are mentioned repeatedly across the album, and appear as a lens through which Cave jousts with his views on wonder and creativity. “We are all so sick and tired of seeing things as they are / horses are just horses and their manes aren’t full of fire / and the fields are just fields and there ain’t no Lord.” Better, this seems to ask, to find the wonder in the horses than to give in and be resigned to the purely literal. “We all rose up from our wonder” he croons on ‘Night Raid’, “we will never admit defeat.”

God on this record, as is always the case in Cave’s work, is very much in the house. Jesus lies in his mother’s arms, priests run through chapels, Jesus freaks are out on the street. It’s no surprise though that Christian imagery pulsates harder than it has done in Cave’s writing for decades here at the point when he is most concerned with wonder – Cave has long linked the religious impulse with the creative one. In his 1996 lecture ‘the Flesh Made Word’, Cave explained that “Christ shows us that the creative imagination has the power to combat all enemies, that we are protected by the flow of our own inspiration.” That other messiah, Elvis, also makes a cameo on ‘Spinning Song’ – where 1985’s ‘Tupelo’ saw Cave depicting the creation myth of Elvis’ birth, here it’s the bloated anti-hero who ‘crashes onto a stage in Vegas’, Elvis of the later years, the fall from grace(land). Falling and rising happens a lot on this record, “a spiral of children climbs up to the sun” on ‘Sun Forest’, whilst on ‘Waiting For You’ bodies become “anchors”, bodies falling “that never asked to be free“. I don’t want to dwell on quite what it is that Cave evokes here.

The closest sisters to Ghosteen are Cohen’s You Want it Darker and Scott Walker’s Tilt – like both of those artists, Cave is in the small pantheon of songwriters who can claim genuinely revelatory late periods. Warren Ellis’ electronics – picking up not just from Skeleton Tree but from the film soundtrack work on which he and Cave have been moonlighting – here are at their most dominant and at their most astonishingly beautiful. The arrangements are often sparse and percussion is barely existent, occasionally pattering in and out of view absent-mindedly (one wonders if Jim Scalvanos got proficient at chess during the recording). Where once the Bad Seeds were marked by their bombast, now their sound is as elusive as Cave’s writing can become – Ellis’ synthesizers glow and swell, and occasionally like on ‘Galleon Ship’ they wail like the top notes of anxiety. It underlines the extent to which this is music made by someone in the aftermath of the unspeakable. On Skeleton Tree Cave’s voice was a often a rasp, pushed to breaking point and for very obvious reasons sounding under strain – these cracks were, of course, how the light got in, but it’s a delight to listen to Cave on this record delivering a career-best vocal performance. The weathered baritone is more powerful than ever, and the most affecting moments on the album see Cave creasing – making itself small – into a tortured falsetto.

Of the three ‘parent’ songs, the strongest is ‘Hollywood’. Ellis’ electronics here are at their most malevolent, and Cave alternates between vocal registers to suggest two different stories being told – one of Kisa, forced to bury her child, and one of another person (Cave?) fleeing to Hollywood after a tragedy (Cave has spoken in interviews of considering relocating to Los Angeles, Brighton carrying too many memories). There’s absolutely nothing redemptive about this album – why would there be? – but one moment offers hints about what comes in place of redemption, which is a roadmap through the worst of it. “I think my friends have gathered here for me” sings Cave on the gorgeous ‘Ghosteen Speaks’, as his friends the Bad Seeds chime a celestial choir around him, “I think they’re here for me.” It’s all we can ever ask from anyone.

On One More Time With Feeling Cave railed against the empty platitudes that surround the language of grief – on the album’s title track, he’s found something succinct and beautiful to say about grief, and I’ll leave the last word to Cave, back in the office, working through pain. “There’s nothing wrong / with loving something you can’t hold in your hand.”