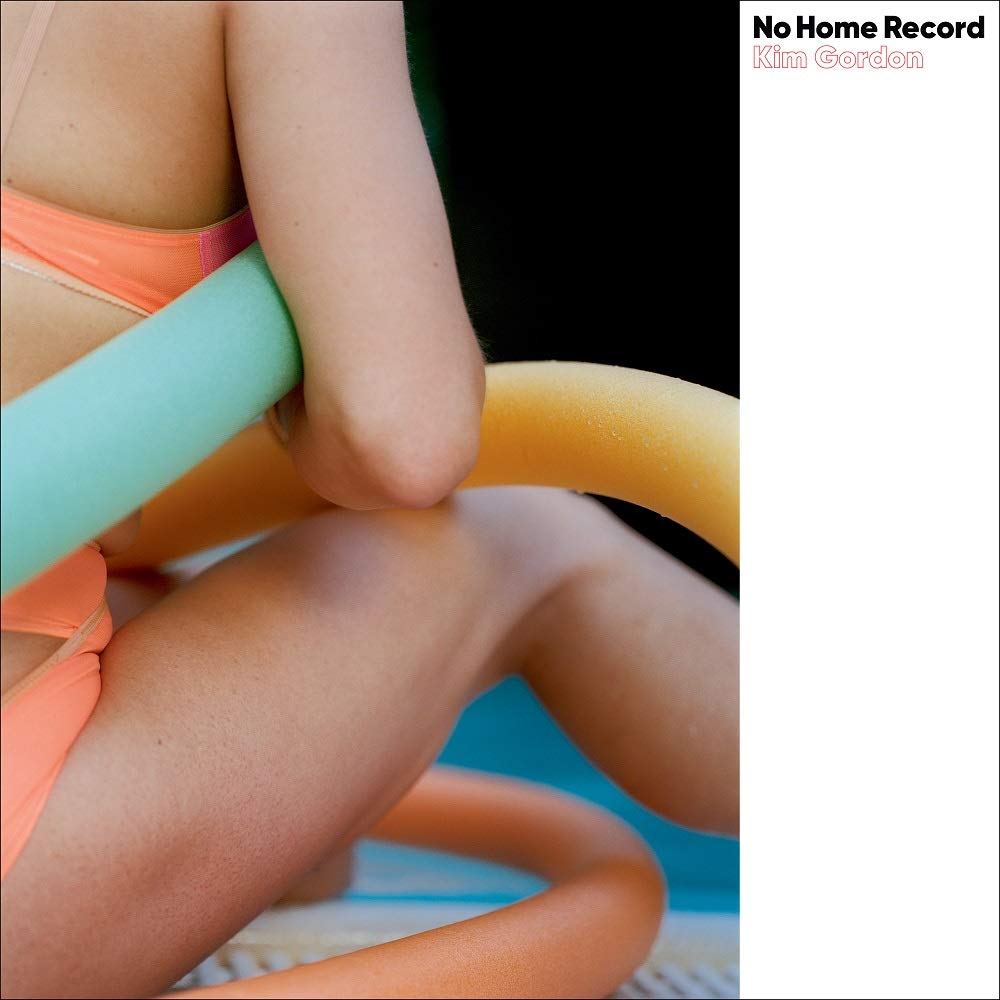

Kim Gordon No Home Record

In a particularly boring conversation between Kim Gordon and Sleater-Kinney’s Carrie Brownstein four years ago, Gordon breaks into laughter at what she calls “the gift of Airbnb”. It was the enabler that gave her enough headspace to write the book that she was promoting at the time, Girl in a Band, but it quickly turned into its own advert for the couch-surfer and hotelier’s dream alike. For an artist, Airbnb was simply a cheaper way to go on a writer’s retreat: you’re in a clean space stripped of sentimentality, nostalgia and history. It’s harder to become distracted without a feeling of attachment to your surroundings; it’s not your stuff. And with that, you’re free to fake a new beginning, based on whatever uncannily intimate experience has been marketed at you with algorithmic precision.

Finding the artist’s utopia within an Airbnb stay has become a gradually less funny concept for Gordon in the passing years – it’s just what she does now. At the time of writing her book, she was working on a transitionary piece of visual art linking New York’s condominiums with noise bands and taglines: Thor, Fortress of Glassitude, Bauhaus inspired living. Absent landlords were devoid of time to oversee the beautification of a city they weren’t living in, and as their cash rebutted a will to integrate within the city’s culture, Gordon at least tried to incriminate the commerce within the dissident sounds of the city. New York was crudely left – in her words – as one large and expensive garden.

Earlier this year, too, as part of her first time exhibiting at the Andy Warhol Museum, she included a series of nude drawings on tracing paper called ‘the Airbnb Series’. They rendered the hotel room as a modern landscape that blended intimacy with publicity. Your most precious travel memories made and consumed within a thumbnail picture of the perfectly displayed towel rack. If John Constable were still alive and painting, you could forget the well-oiled canvases of Hampstead Heath. Here’s a triptych of rooftop terraces close to the city center, suitable for 4-6 guests, on wood and acrylic.

On Kim Gordon’s first solo album within a 40-year career you only have to make it past the opening track to hear the agitated rock intro of a new song, also called ‘Airbnb’. It suits the artistic trajectory of No Home Record to a T; freedom, fresh in a city to-be-discovered. But pre-curiosity comes the quest of how you should enjoy it. Gordon sings through advertising pages of slated walls, 47-inch flat screen TVs and a lounging daybed, or the alternatives of cozy and warm apartments with blue tiled floors and a free water bottle from your super-host or super-hostess. A relief, at least, that her legacy can afford her a greater decision than picking between cardboard rooms in Bournemouth, advertised only by there being both a hot and a cold tap. A thrashing chorus begs for a cleansing space to start the record – “Airbnb/ Gotta set me free” – and it seems to have worked. Like every resistance to the formula from Kim Gordon before, this isn’t how you thought she’d sound.

Each song at its core orbits around this dichotomy of returning home – to a place that knows her as well as she knows it – and yet still yearning for that scantily-phrased new beginning. Thematically, it’s the same hymn sheet as the one she’s been all but singing from in the fissures between her musical output. But there’s only a certain amount of history you can get rid of when you’re Kim Gordon, regardless of any well-spent artistic allegiance to a lack of familiarity (and, for that matter, no matter how empty the Airbnb). Her breathy voice is as iconic now as it was as one of the first women of rock’n’roll, co-anchoring Sonic Youth at the forefront of an alternative noise rock scene for three decades.

No track panders to the confusion as much as the re-contextualised ‘Murdered Out’ – the first song she released in isolation under her own name three years ago. A corrosive loop breaks over the carefully sculptured feedback to sexualize a bleak and tensile soundscape of a time in Southern California’s automotive past, where vehicle owners would obscure their windows with black matte spray-paint. Car brand badges and number plates are murdered out in an act of soul-purging, thick with a Downward Spiral-era Nine Inch Nails bassline and the frenetic electro gravel of Pigface’s Fook. Gordon’s seditious vocals are barely breathed over the top of a percussive beat from Warpaint’s Stella Mozgawa, funkier and more intricate than anything normally brought forward from Sonic Youth.

It’s the opening track ‘Sketch Artist’ that is still No Home Record’s unwavering, restless masterpiece – a piercing sonic exploration of a death stare through mechanised acerbic glitches, daring you to question its lyrical tics: “You’re a mystery, like a horse.” A less cryptic horse is ‘Paprika Pony’, at the other end of the sensuous spectrum: an industrial bump’n’grind cross-examination of female identity in the midst of a dancehall beat. Gordon’s rasping cadences barely break into song, discussing the loaded phrases that signify femininity: “What am I? Just not a girl. A woman.” The enveloping motoric deadpan instills a similar instinctive urgency to ‘Don’t Play It Back’, itself an off-kilter club track with a similar wasteland urgency to the avant-diatribe euphoria of Robyn’s work with La Bagatelle Magique. Both hurtle back to Gordon, laced with anodyne licks and an unsettlingly expressionless, subtle politics: a sturdy experimental peer to the electrifying riot grrrl feminism of Bikini Kill and Brat Mobile.

Even without the politics, anti-musicality and anti-precision are countered by a heavy and deft improvisational tone, never quite mastered in her work with Body/Head. No Home Record is spattered with tongue-in-cheek wordplay and a humour that has in part come from thirty self-confessed years of not knowing how to play an instrument. The battleground between ‘Cookie Butter’ and closing track ‘Get Yr Life Back Yoga’ puts condiments against each other. The former finds its amidst an abstract spiraling love story (“You fucked/ You think/ I want/ You fell”) and its only resolve is “cookie butter”. The final track instead annuls its sensual narrative with a kind of culinary petrichor, where “everyday things smell like dark chocolate cocoa butter”. But as you pick your favourite lard-based spread, the expansive Moroder-esque helicopter drones engulf you, and without Bill Nace’s softly sprawling guitar, Gordon sounds both like a sermonizing Patti Smith at the peak of her Beatific rock summit, or like Cosey Fanni Tutti sewing together the hiccupping synths of her post-Gristle comeback.

The only song free from Gordon’s political hand on No Home Record is ‘Earthquake’, a tender and – in the record’s context – almost obtrusively quiet love song: “This song is for you/ if I could cry and shake for you/ I’d lay awake for you.” Gordon’s wavering vocals are the centerpiece of the music for the first time, and it’s the first time too that you can hear a maturing fragility in her voice. Does “sonic youth” change its meaning when you’re in an age bracket that gives you free bus travel?

No Home Record may be heavy with corporeal, corrosive loops and enough experimental flicks and discordant dynamism from Yves Tumor producer Justin Raisen to wilfully turn off the MTV faithful, but it still ends up with a definable melody at its close – not unlike the depths of alternative music culture that Gordon made strangely and critically accessible. Scraping away the advertised and commercial clunk from her reading of L.A., each track unspools as part of the mythical resistance to what you want Kim Gordon’s first solo record to sound like. It’s almost like she doesn’t see this as quite the occasion that her fanbase does. The question of Nutella versus Biscoff doesn’t have an answer, and neither does anything else. It’s enough of a sonic clear-out for Gordon to become rock’n’roll’s Marie Kondo, but as she’s previously confessed, doing anything radical is far more interesting when it looks benign and ordinary from the outside.