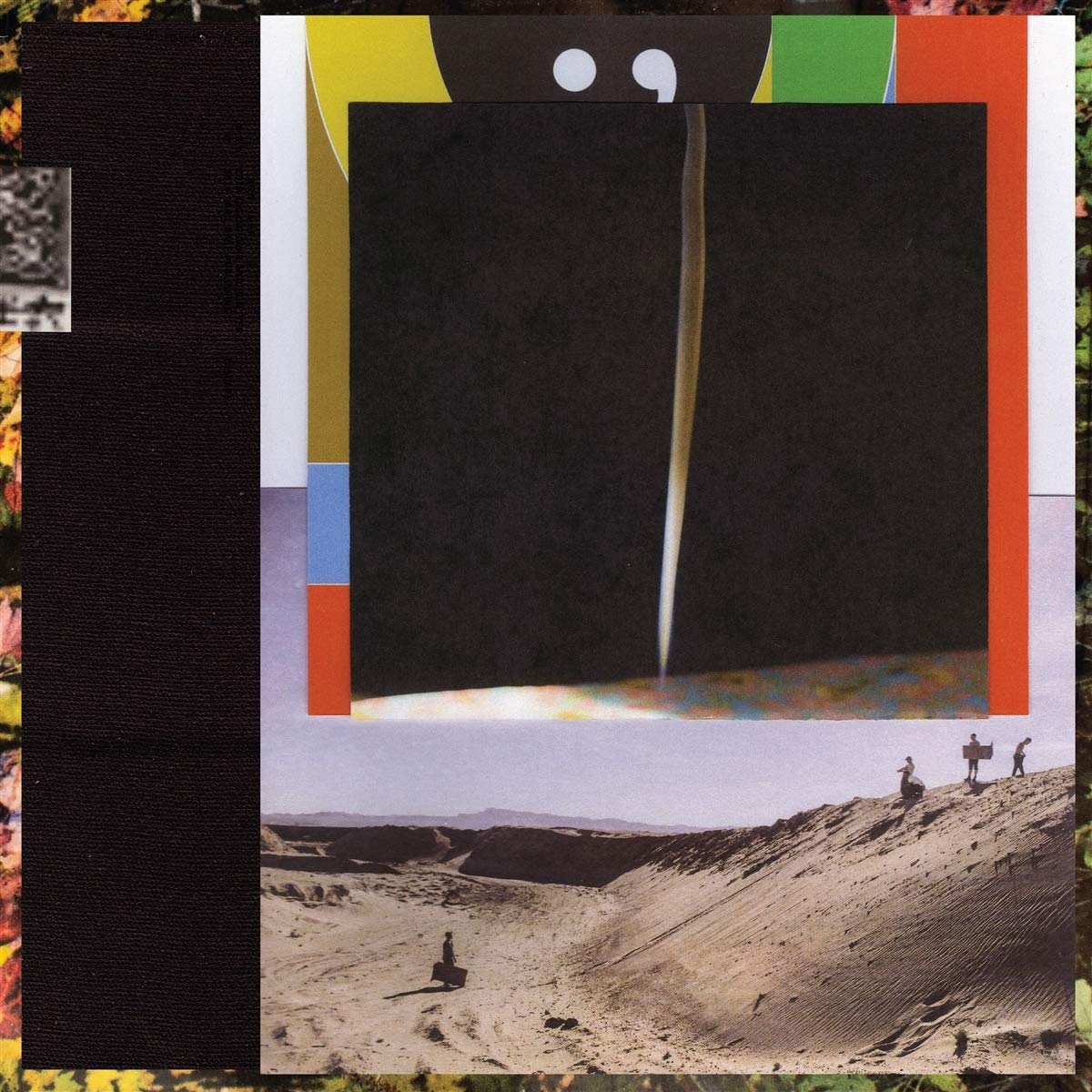

Bon Iver i,i

There’s something in the kitsch quote, familiar only to meandering relationships and over-dramatised television, that strikes a little pertinence in the last decade’s worth of Justin Vernon’s music, at least – “it’s not what you said, it’s the way you said it!” It’s the lucidity that’s given him a free run-and-jump at inventing his own language; how he justified being both “fuckified” and the “Astuary King” in 2016, with a mumbling auto-tune and more punctuation in his variegated cut-n-paste song titles than recognizable words.

These fractured kid’s-sat-on-your-keyboard formalities wilted some piebald logic in and of themselves, distancing Vernon from a crowd that had, at times, outgrown his band. They were a small reflection of the anxiety and panic attacks that had grappled at the woodland cabin man turned pop-star: he bypassed traditional intimacy in a way that wasn’t meaningful by language’s own standards, but that was always received with a genuine understanding from his audience. Just watch the crowds sing ‘re:Stacks’ back to him, and name another performer that could draw tears from the line “this my excavation and today is kumran” (a deliberately misspelt reference to an Israeli national park).

Three years doesn’t feel like such a long time to have waited for new music since 2016’s near-perfect 22, A Million. It helps that he filled the aperture between then and now with a proverbial shit tonne of new music: Big Red Machine with The National’s Aaron Dessner, a three-song investigation into movement with TU Dance called ‘Come Through’, two iterations of PEOPLE Festival and the coinciding 37d30d platform, with enough hidden demos to fuel your buy-in to the whole join-us-as-we’re-making-it mission. In Vernon’s quest to curate a new way of interacting with music and community– beyond music for music’s sake and in awe of the mistakes that come with awkward collaboration– his manifesto for patience has been off-set with enough generosity for it not to really be tested.

But with that non-stop slight of anti-commerce, i,i is the perfect follow-up to his previous work. A lot of it plays as an amalgam of Bon Iver through the ages; it’s the chronological “Best Of” for the times you might have missed. There’s a little more humouring the games of “who’s here for ‘Skinny Love’?” – the delicacy of For Emma has its bare bones structure in more of this music than any of his albums to date. ‘iMi’ might be flecked with the momentary alien dives of auto-tune and sampled voice rhythms from long-term co-producer BJ Burton, but the wordless vocalisations in ‘Holyfields,’ are more Peter Gabriel than the big experiment.

Within the meta-retrospective, i,i is still brimming with the youthful curiosity that could slot into any moment of Bon Iver’s three-album past. Vernon is burning the candles of nostalgia and urgency in equal measure. ‘Hey, Ma’ in the album’s context is a slow-burning classic, reflecting the impressionistic and despondent workings of adulthood: subdued in responsibility while yearning to be looked after. Even ‘Naeem’ – a blazing standout with the spirit of the West Coast Get Down and the revolutionary keys of ‘Sinnerman’ – has a paternal energy in its studio re-working that was missing from Primaveras past: it’s an inductionary descent into madness and faltering paternity. In Vernon’s mix of heady vocal gravel and insanity, lines about dope – “I’m having a bad, bad toke” – come with the desperation of The National’s “became a father when I was still a son”, where social responsibility comes with the longing to experience childhood again.

Elsewhere, Mike Lewis’s heavy gravity saxophone wafts vivid reminiscences of 2011’s self-titled album on ‘Sh’Diah’ (an abbreviation of the Shittiest Day in American History), a sad-lad party whose harmonies rarely resolve. Collaborations with Moses Sumney and Velvet Negroni add a slap-happy falsetto to the melancholy. On ‘Jelmore’, the same multi-tracked wheeziness sounds like life support, with Francis Starlite’s occasional dance tinges playing like a bad break-up amidst a shopping mall flash mob.

Bon Iver is still a young band, despite the status that strings of stadium tours and festival headline slots have afforded them. It was only a decade or so ago that For Emma, Forever Ago became the veneration of the American MySpace dream. The dual strands of community and intimacy that cling to the walls of i,i like residue contain its real strengths. From the rust descending on the opening glitches of ‘Yi’, to the skit of Vernon’s excited mid-rehearsal calls– “are you recording this, Trevor!?” The punctuation that served prismatic purpose on 22, A Million is looking backwards on i,i, filling in the gaps of a catalogue that has quietly engrained itself in the canon of independent music, but still plays with the inquisitiveness and freedom of cats in the nighttime.