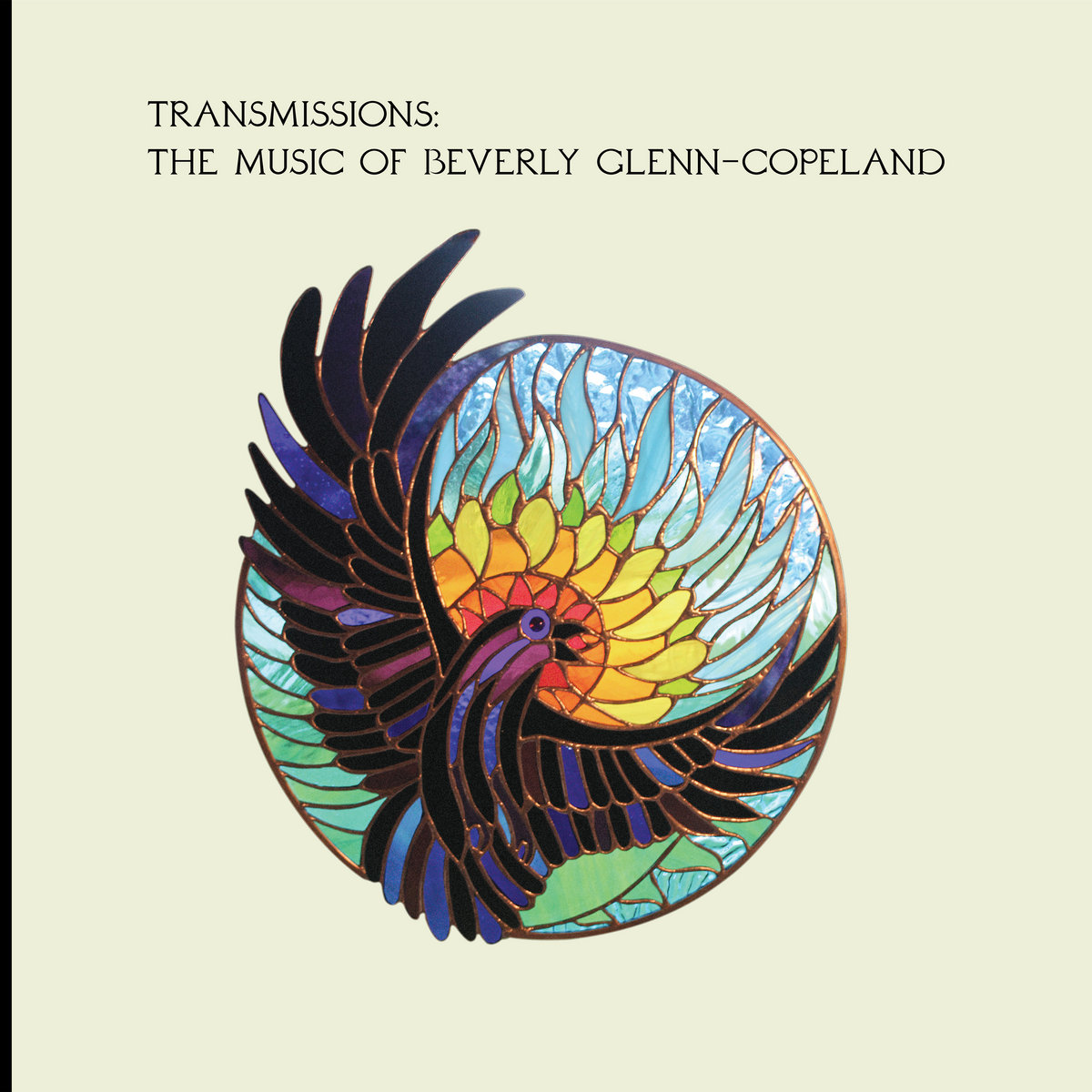

Beverly Glenn-Copeland Transmissions: The Music of Beverly Glenn-Copeland

A greatest hits album is usually fail-safe. It’s a shield to protect against particular commercial or critical flops; a fan’s reminder of an artist’s past golden age in spite of perceived diminishing returns. In the case of Transmissions: The Music of Beverly Glenn-Copeland, it feels rather more like a long overdue introduction. Beverly Glenn-Copeland, now a septuagenarian, never met with the same widespread acclaim of his peers in new age music. His releases were too sporadic and, as is the case with the majority of early electronic music, the world never quite seemed ready for what he had to say. However, this isn’t to say that Glenn-Copeland won’t have drifted within earshot for you before.

I first heard the looped opening bars of ‘Ever New’, which first appeared on Glenn-Copeland’s cult 1986 LP Keyboard Fantasies, as a regular feature of a pub quiz night, fed gently through the speakers during the drawing round. Its swirling, pitched percussive notes brought to mind using Microsoft Encarta ’98, or some similar virtual encyclopaedia; contemplative but playful, as charmingly antiquated as library music. If Transmissions has one strength above the rest, it’s that it transforms background music into music for tearfully slumping at four in the morning, alongside Glenn-Copeland’s cradling lullaby; “welcome the child, whose hand I hold / welcome to you, both young and old / we are ever new, we are ever new”. It’s achingly beautiful, like a hymn from childhood creeping back into memory. It’s some small blessing to have the ability to scrub back through its gently popping rhythms, back to its beginning, over and over again.

Much of Transmissions deals with re-stagings and re-contextualisations, and nowhere is Glenn-Copeland’s own changing attitudes towards his music felt better than in its wealth of live renditions. Recorded around 50 years after its initial release on Glenn-Copeland’s 1970 self-titled soul-jazz LP, ‘Colour of Anywhere’ is here slowed down to a glacial glide, allowing Glenn-Copeland’s tremolo vocal the space to yearn harder than he did at 26: “I won’t ask how long you’ll love me babe, though it’s on my mind”. The object of his desire is always deliciously slippery, a lover he can’t quite reach or a grander interconnectivity with higher powers. Lifted from a performance at Utrecht’s Le Guess Who? festival, ‘Deep River’ in particular serves to demonstrate Glenn-Copeland’s ability to connect as a frontman, inviting crowd participation with the warmth of a beloved children’s TV presenter.

As remarkable as Glenn-Copeland’s recent, groove-oriented work is — and ‘In The Image’ in particular — they’re even more so for the achievement of neatly framing themselves next to his folk-styled ’70s output — songs like ‘Don’t Despair’, ‘Durocher’ and the lithe acoustic prog psalm ‘Erzili’. It’s a clear indication of Glenn-Copeland’s consistent voice across the decades. It makes being enamoured with chameleonic artists, bending to the whims and demands of musical eras as they face fading from the cultural landscape, seem much too easy. It takes a monkish kind of visionary to chase the vision presented by their earliest epiphany. Mark E. Smith did it, as does Ryuichi Sakamoto. Transmissions is testimony to the fact that Beverly Glenn-Copeland should be counted among them.