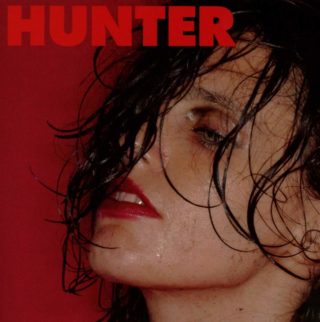

Anna Calvi

Hunter

(Domino)

7/10

(Domino)

7/10

An exercise in uncensored honesty, ‘Hunter’, the third album from art-rock musician Anna Calvi, is a galvanising record that, at its heart, embodies the freedom of true release. Written during a turning point in her life – the breakdown of an eight-year relationship and a move to Strasbourg with a new partner – it’s the tool through which the south Londoner was able to reimagine and question her own identity. “My girlfriend encouraged me to explore myself in a way I never had before – I was exploring pleasure, and my sense of gender, which is something I had been suppressing for a long time. Through the process of making this record and writing these songs I found myself questioning whether I wanted to identify as a ‘woman’, with the limitations that label brings,” explains Calvi. “As well as my very own intimate journey exploring my sense of gender, I was inspired by this electric moment of artists and the wider community talking about gender and sexuality. I wanted to write an album where the woman is seen as the hunter, rather than her usual stereotypical role in our culture as the hunted.”

With primal percussion, unleashed guitars and arresting lyricism (her recording band included members of The Bad Seeds and Portishead), Calvi pushes the boundaries of her instrumentalism and vocal skill here in a manner that perfectly mirrors her internal struggle against the confines of preconceived notions of gender.

The album’s lead single and focal point, ‘Don’t Beat the Girl out of my Boy’, is a raw and wild celebration of unbridled freedom and defiant happiness. Infectious in its empowering and climactic vocal melodies and heart-beat drum rhythms, Calvi says that the song is “about being free to identify yourself in whichever way you please, without any restraint from society.”

This theme – one that permeates the entirety of the album – is particularly notable in ghostly closing ballad ‘Eden’ and the David Hockney inspired ‘Swimming Pool’, both of which see Calvi envisioning a utopian alternative to contemporary society, constricted by the trappings of exclusive social and ideological frameworks. The former, complete with saintly vocal and a shimmering melody, narratives the purity of a tryst with a new lover, reimagining the difficulty and pain of queer adolescence as an idyll. Using glimmering, harp-like guitar lines and repeated vocal refrains, the latter perfectly captures the summer-hued and unrestrained queerness of Hockney’s 1960s artworks. This is Anna Calvi, a trio of albums in, turning unrest into contagious liberation.