What the television did to us

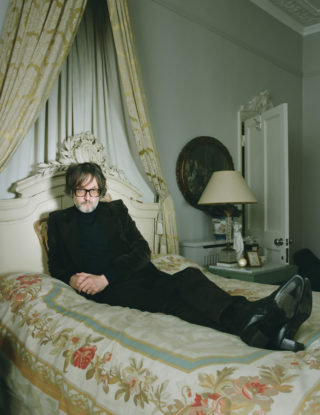

“I have a thing in any hotel I stay in now where I try to unplug the TV and put it in a closet,” says Jarvis. “Or I just put a coat over it. I don’t like it. I feel like I watched so much TV as a kid that I’ve done my time; I don’t need to watch it anymore.”

‘Interlude 2 – 5 Hours A Day’ is another David Thomson track, featuring just two sentences from the historian: “The fact of the matter is, if you’re average, you probably grew up watching 5 hours a day. Now, I bet you didn’t spend 5 hours a day talking to your parents.” That was Jarvis Cocker, who, along with the other children of the late ’60s and early ’70s, gorged on the new medium of television.

When Jarvis’ father disappeared when he was seven, he says he started to look for clues on how to be a man from his beloved TV that puzzled and thrilled him.

“Which is a terrible place to look,” he notes. “I mean, I was never going to be a cowboy or a rugby player, was I?”

‘Interlude 2’ is then followed by a song called ‘Daddy, You’re Not Watching Me’, and early on in our conversation Jarvis pointed out that although Chateau Marmont is a place full of fanciful legends and fruitful inspiration, ‘Room 29’ needed to be personal to him, not just a bunch of stories about other people going wild on Sunset Strip. “There would’ve been no point making it a docu-drama,” he said.

He nods at the flat screen that’s out of place in this French period room. “Some people have trained themselves to ignore the TV in the room, but I can’t. Even the fact that that telly is there now is a little bit disturbing, but if it was on, our conversation would quickly grind to halt. Not because I’m not interested in you, but because, it’s like I’ve got a respect for moving images in some way, and it hypnotizes me. I hate when you go into a bar and there’s a telly because I’m sat there thinking, why am I looking at that – I’m not interested in… hockey. And that’s part of what I was talking to David Thomson about.

“What got me into him was he’d written this book called The Big Screen: The Movies and What They Did To Us. So he’s a good writer on the subject of how movies have affected human beings – it’s got into our DNA, in a way.”

He reflects on how moving image must have seemed like magic at the advent of the cine camera, and how we’ve become immune to pictures with movement in the modern age, as we trundle past them on tube elevators as easily as we look at them on our phones for fear of being under stimulated while the bus takes another 60 seconds to arrive. “It’s a shame, because it should still be exciting that you can capture reality. It’s almost as if moving image has replaced reality.”

Jarvis’ relatable fascination with film and television is only half of ‘Room 29’’s dreamland, though. Chateau Marmont is in the middle of Hollywood, and intrinsically linked to the magic of movies, but in its simple form it’s a hotel, and hotels come with their own fantasies, regardless of where they are.

Jarvis tells me: “When I was a kid, and maybe this is one of the roots of this record, I remember at the age of 8 or so, my ambition was to live in a hotel and be rich and have enough money to pay a servant to project my favourite television programs whenever I wanted, which at that point were The Monkees TV show and Batman. That was my ambition – you’re in a hotel so someone else will make the bed, I’ll just ring down for food and the tray will disappear afterwards. All that stuff. Embarrassingly enough, I think that ambition stayed with me for a long time.”

Until when, I ask.

“Probably until about a week ago.” He smiles and then laughs. “Of course, now I could do that. I can afford to check into hotels, and I wouldn’t need the servant, because in the interim Blu-Rays and DVDs and streaming were invented.

“I don’t know if I’m totally alone in that ambition. It’s that thing of not wanting to commit to anything, and just wanting to slide through life, without having to pick up your own mess or really get involved too much.

“You could say that part of this record is exploring that. Where did wanting to live like that come from when I was a kid?”

The thing about a hotel room is that it’s a blank page, he says. “I think that’s why people can lose it or break down in a hotel room. Because at some point you’re just faced with yourself.”

Jarvis pulls out his phone to read me a quote from British writer Geoff Dyer, which he wanted to use in ‘Room 29’ but didn’t manage to get clearance on in time. He swipes back and shows me some other research photos he’s taken – a Photoplay fan magazine from 1917, outlining a manifesto for Hollywood on how all films should have happy endings, and the stylish Do No Disturb door hang from the Marmont.

“Right. Here’s the quote,” he says.

“Hotels are synonymous with sex. Sex in a hotel is romantic, daring, unbridled, wild. Sex in a hotel is sexy. Even if you’ve been having a sexy time at home, you’ll have an even sexier time in a hotel. And it’s even more fun if there are two of you.”

Naturally, his reading of this is knockout, while ‘Room 29’’s opening title track has Jarvis loudly whispering the rather more blunt, “Is there anything sadder than a hotel room that hasn’t been fucked in?” It’s almost enough to distract you from the line in the chorus that starkly sets out the record’s true reflection: “Room 29 is where I’ll face myself alone.”

“I think as soon as you walk into a hotel, you’re already starting to come up with some fantasy of what you should be doing in the hotel. Especially if you’re living in a hotel like the Chateau Marmont, with all this back history. I think that can cause people to have episodes and issues, because it reflects back on you what you are.

“I am fine with hotels now,” he says when I ask. “I no longer have any episodes. I enjoy them for what they are. But especially with rock’n’roll things, there’s an idea that – not trashing the room, because I always thought that was stupid – but that you should be doing something newsworthy. You might just want to be tired and have a lie down.”

He tells me that the live show tackles the myth of rock’n’roll excess in hotel rooms, although he doesn’t tell me how for fear of ruining what he describes as “quite a big moment” in the performance. Perhaps it will be illustrated with the ridiculous story of John Bonham riding his Harley Davidson into the lobby of the Chateau Marmont – the biggest cock-swinging moment in ’70s rock history, which Led Zeppelin would repeat at the neighbouring Continental Hyatt Hotel (‘The Riot House’). And yet a story like that feels a little too low-rent from ‘Room 29’.