After the freeze: what’s next for Britain’s DIY music scene after the pandemic?

A host of independent voices from across the UK share their thoughts on what now

Matt Baty lets out a long sigh when I ask him about his 2020. “I’m not going to lie; it’s been stressful at points. We’ve pretty much had to freeze everything.”

Until the pandemic hit, Baty’s band Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs Pigs was all set for a breakthrough year. Their third album, Viscerals, was getting significant airplay, and they were all set to head to the States for shows at SXSW and a short tour. Instead, they found themselves forced to kick their heels. “Our guitarist has cystic fibrosis, so he’s had to shield the entire time, he’s literally been unable to leave his house in 12 months, and as you’d imagine, it’s been pretty difficult to do anything without him. Our band only really works when we can all get together, and you can count the number of times we’ve managed that on one hand. Suffice to say, we didn’t get a lot done.”

By no means typical, Baty and Pigs’ experience is a pretty good illustration of the corrosive effect COVID-19 has had on Britain’s grassroots music scene. It’s stating the obvious that music is a collaborative effort, and the virus has attacked the connections between communities just as relentlessly as it’s attacked airways. Across the country, musicians have had to overcome significant barriers, from finding new ways to work together to reaching out to fans and making money. However, while the disease has affected everyone, it certainly hasn’t affected everyone equally.

“It’s definitely been a journey,” Sinead Mills of Hoof Management tells me as she runs through her experiences of the pandemic. Looking after artists like Squid, William Doyle and Lazarus Kane, Mills and her fellow managers Tash Cutts and Ina Tatarko have had an equally fraught year, but somehow managed to keep productive.

“The uncertainty has been tough, especially seeing tours and recording sessions wiped from the calendar over and over again; however, everyone has adapted incredibly well. There’s been a lot of music and ideas shared digitally and a hell of a lot of Zooms.” In the main, Hoof’s story of the pandemic has been a model of DIY resilience. Squid, for example, wouldn’t have been able to release their debut album Bright Green Field without the generosity of the local community – local Chippenham pub The Old Road Tavern allowed the band to create a bubble and use the bar to write and rehearse new material.

“Other artists like William Doyle released an album that he salvaged from a hard-drive crash,” Mills adds, highlighting how Hoof’s other artists had kept active during the pandemic. “He probably would’ve just ignored it if he’d been on tour or in the studio working on a different LP.”

The pandemic might’ve hampered the ability to make music, but the DIY ethos has allowed many acts to power through. Artists have leapt logistical problems with not much more than a can-do attitude. Practices have been replaced by Zoom sessions, songwriting has been conducted over WhatsApp, live gigs streamed over Instagram and records sold through Bandcamp. Emotionally though, it’s been a different story. A year of forced isolation and endless uncertainty has taken a toll on many of the artists I spoke to. A lot reported that they felt split off from the support network and feedback loops that often sustains music scenes. According to a study from the charity Help Musicians, nine in ten artists have struggled with mental health issues over the past 12 months.

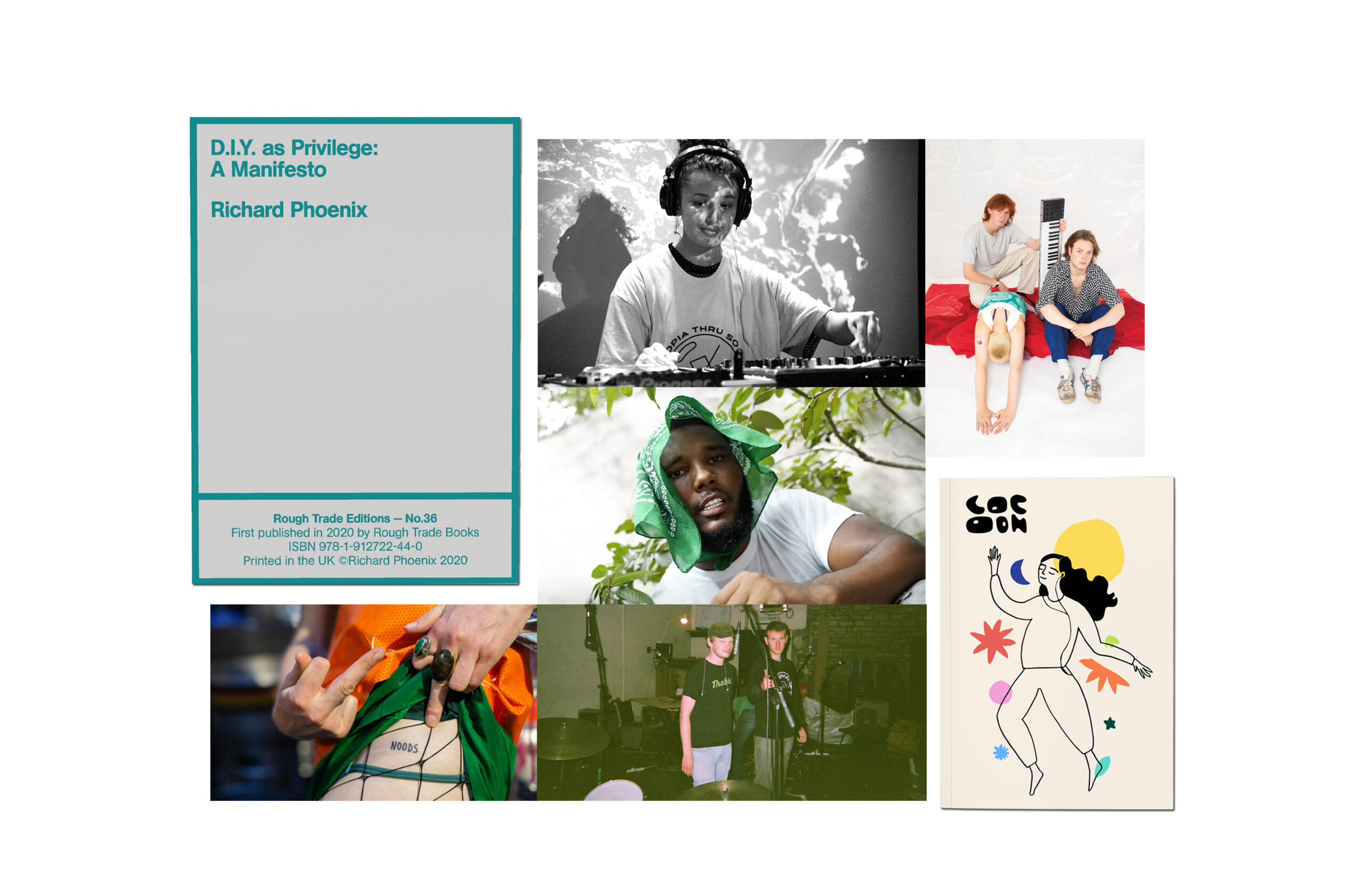

“I’ve found it really hard to be creative,” Trish Khallagi tells me over a Zoom call. DJing under the moniker of K Means, a name taken from her day job as a software developer, before the virus hit she was building a steady reputation in the darker and weirder regions of electronica through shows across Southern England and a regular show on Bristol’s Noods Radio. “I’ve always felt like I was halfway between an extrovert and an introvert, but the last year has shown me how much my creativity stems from other people. As a result, my motivation has really suffered. I’ve tried to do as much as I can, but I’ve also ended up postponing a lot of things. I’ve struggled to do things at the frequency that I’d normally do things.”

Music without fans

Even before the COVID hit, eulogies have been whispered over the coffin of DIY. As far back as I can remember, op-ed after op-ed has been lamenting the slow collapse of the ecosystem that makes underground music possible. First, gentrification made it harder for budding musicians to find affordable practice spaces or places to perform. Next came a remodelling of what had been a supportive music press – the demise of traditional advertising and the rise of pay-per-click resulting in more coverage of established artists and less support for new music. The final blow had been streaming. What was promised to be a democratisation of music has become a double-edged sword. On the one hand, streaming makes it easier for fans to discover new artists. On the other hand, the unfair payment structures and closed-shop business practices have led to many small artists and labels receiving only a pittance for their work.

The thing is, though, while all of the above is true, it’s only ever been part of the story. Time after time, the DIY music industry has found a way to survive and thrive even as the rug felt like it was being constantly pulled from under it. Take South London, for example. In an area that’s often been held up as a case study for rampant gentrification and diminishing numbers of art spaces, a scene of bands has coalesced around the Windmill pub and venue in Brixton, producing the likes of Black Midi, Squid, Black Country New Road and Goat Girl in a few short years. Just behind them, PVA were poised to follow. I interviewed them at a stylish Deptford art cafe back in the late summer of 2019 and was immediately taken aback by their willingness to re-engineer the established dogmas of DIY music. At the time, the band managed to pack out venues on the back of only half a song’s worth of recorded music. Instead, the band was using a combination of social media, word of mouth and a well-honed live show to grow a large following of devoted fans who were creating a real feeling of buzz around the band.

With COVID splitting musicians from their fans, I caught up with PVA to see how they’d adapted. “We’ve always been a band that relies on live events to reach our audience, so the transition from a stage to our bedrooms has been an interesting one,” says frontperson Ella Harris. “Playing live has always been such a crucial part of the process; we’ve always found it hard to realise a song until we’ve played it at a party or a gig. Then again, being apart during the first lockdown allowed us to explore our own approaches to music.”

Going even further, a few artists have navigated the difficulties of last year seemingly without breaking a sweat. “My career’s taken off during the pandemic,” Birmingham-based rapper M1llionz tells me from the studio he’s using to make the finishing touches to his record. “I’m really not all that accustomed to live performance. Don’t get me wrong, the lack of face to face interaction with my fans has been tough; I’m definitely looking forward to performing, especially as my fellow artists have told me it’s one of the most enjoyable parts of the job.”

Part of the Midlands’ fast-rising drill scene, the pandemic has only really been a speed bump for M1llionz. The ongoing criminalisation of drill had effectively taken live performances off the table for many up-and-coming rappers, meaning that many had turned to technology to reach their fans even before lockdowns and venue closures. “Live streaming has been a saving grace through all this,” he continues when I ask him about his experience building a rep over YouTube and Instagram. “Social media has been really important because it builds up attraction around a release. It’s great for promotion – my fans get to know me better, and they can see what I get up to.”

Similarly, down on the south coast of England, I found another group using technology to redevelop the link between artist and fan. Richard Phoenix has been involved with DIY music since becoming a member of Sauna Youth; he now works with musicians with learning difficulties and autism.

“I have to say, my experiences of the last year have been remarkably positive for the most part,” he recalls from his home in Hastings. “It’s opened up a whole new way of thinking about music, from finding ways to collaborate to bringing artists and audiences together through virtual gigs and live streams.”

“In a lot of ways, I feel like the pandemic has opened music up to a lot of people. Using tools like Chrome Music Lab, we’ve been able to organise things that would’ve been an absolute nightmare in real life. If you wanted to find 20 people to jam on one track, in the past you’d need to find a space, loads of equipment and solve the access problems that come with that. With the internet, though, it’s all relatively straightforward. It’s allowed people to be involved with music in ways that they’ve never been able to do before, from interactive shows to collaborative sessions. It’s really breaking down the performer/crowd dynamic and is actually helping to open up the experience to everyone.”

Dormant or dead?

Social media, live streams and WhatsApp jam sessions might have kept the lights on for many acts and fans, but now that infection rates are falling and venues are opening up, Britain is poised to get back out there. Industry body LIVE recently surveyed 25,000 music fans and have found that demand for live shows has never been higher. Over 75% of fans are either ready to hit a club right now or are happy with only the smallest amount of mitigation measures in place. There’s also a yearning for everything to go back to how it was, with 53% saying that they’d attend gigs with no extra hygiene consideration. In fact, the study found that masks and social distancing were the most likely factors in deterring fans from attending, especially among the youngest age group.

“Honestly, come July, it’s on,” beams Anthony Chalmers, who’s feeling bullish about the months ahead. As well as being one half of the well-respected Independent Music Podcast, he’s the driving force behind Baba Yaga’s Hut, known for experimental nights at Corsica Studios in London and the annual Raw Power Festival. Needless to say, he’s been unusually quiet last year, although the few gigs he did manage to put on hints at the demand bubbling beneath the surface. “I did four shows last year, and while they definitely weren’t the best ones that I’ve ever done, I have to say that everyone went pretty wild. I remember chatting with the booker at the Strongroom after one of them and figuring out that the bar take must’ve been like £30 to £35 per head. I mean, if that doesn’t say that people are excited to be back out there, I don’t know what does.”

Cocoon is Smail’s DIY response to COVID. Born out of the frustration brought on by the never-changing days of lockdown, this zine project is a tribute to the escapist power of music; a collection of essays exploring the connections between music and memory, from retreats into hidden gems, rediscovered desire and memories of old vacations. As well as bringing a community of music fans together, the sales have helped organisations working with marginalised groups, such We Belong, a charity created for and by young UK immigrants, Scottish Women’s Aid and The Black Curriculum.

Smail, readily admitting that he hasn’t listened to much new music over the past year, sounds a note of caution. “While I’m excited to get back out there, I can’t help but think that the virus has made it more difficult for new bands to get a foothold. You’ve basically had a whole year where the only way to discover music has been through social media, and while that’s helped artists survive, I think it’s made grassroots music a lot more cliquey. Even things like Patreon and Bandcamp tend to end up becoming a bit exclusionary. You’re kind of forced to pay for access, and while that’s good as it allows these acts to continue, it does make it harder to just stumble onto a band like it once was. If anything, it makes the role of the press and radio even more important.”

Looking at the numbers, it’s hard to disagree. The pandemic has undoubtedly been tough for the UK’s grassroots music scene, but as each week passes, it’s starting to feel like the problems that are coming with Brexit might be a whole other shit sandwich. A new survey by the Incorporated Society of Musicians and the Musicians’ Union has revealed that exiting the European Union is shaping up to be a hammer blow. Customs changes are due to slap at least £15,000 of additional expenses to acts wanting to tour or sell their music on the continent while significantly reducing musicians’ ability to earn. The survey found that 77% of musicians surveyed expect their margins to decrease, with 21% considering quitting altogether.

Unsurprisingly, it’s leaving people with mixed prospects at best. “It’s more difficult than ever to find the resources to survive as a purely DIY artist,” explains Tash from Hoof Management when I ask her about the viability of the DIY model in the new normal. “Without live music, there have been fewer opportunities for bands to make the industry connections that are often required to help a project reach the next level, and labels may now be less inclined to take risks on new artists. So, even though the DIY model has itself been impacted by the pandemic, it will have to become the predominant method for artists whilst the industry recovers.”

Building up and building out

All in all, it’s been a year of self-reflection, experimentation and innovation, and for the music industry the only thing coming down the pipe is more uncertainty. The pace of evolution has always been fastest down at the DIY level of making music. With big challenges on the horizon, it’s more than likely that the definition of independent music will be changing again. The question now is what should it look like?

“Now’s the right time to pause and think about how we can do things better,” nods Khallagi when I ask her about the direction electronic music needs to take now that the worst seems to be over. “I’d like to see this as a point where we can start doing things differently, such as booking acts that are more local and ensuring that line ups are more diverse, but I do worry that we’ll end up slipping back pretty quickly. DIY spaces are the places that have suffered the most, and unfortunately I can see them falling back on what worked before.”

Unfortunately, the data suggests she might be right. Back in March, the Guardian looked at 31 events planned for the summer of 2021 and found that the issue of gender equality has already fallen by the wayside, with festivals such as Isle of Wight, Latitude, Field Day and Neighborhood all promoting lineups that are 60% male. A Musicians’ Union study back in September, meanwhile, showed that women, gender minorities and people of colour disproportionately affected by the pandemic are calling on industry leaders to commit to better representation.

“There does tend to be a bit of an outdated view on what is and isn’t ‘DIY’,” says Smail when I ask him about the future. “We really do need to change the way we talk about it – it tends to be depicted as this gritty, edgy, punky scene full of white guys with guitars, but DIY isn’t ever just one thing. It really should be a space where people can be anything that they want it to be.”

Phoenix has recently published a DIY as Privilege on Rough Trade, a 13-point manifesto detailing how underground music can be more accessible to people who have usually been shut out. He defines DIY as an ‘idea that anyone is capable of becoming a musician and sharing their music. It empowers individuals and communities, encouraging alternative approaches when faced with obstacles.’ It recognises that underground music is a place where resources are scarce and asks that artists, fans, creators and supporters work to recognise their advantages and ensure a scene that is fair for everyone.

“The big thing gatekeepers need to consider is this idea of permission,” he explains. “As a teenager, I thought it was perfectly reasonable for me to play in a band as all I saw was people who looked like me playing in bands. But obviously, that’s not what everyone sees on stage, or even in their lives, so anything that can give people permission and let them feel like they’re allowed to take ownership, make music and put their ideas out there is really important. We should always be asking who gives us permission to be on that stage and how we extend that permission to other people.”