The young trans and non-binary musicians building communities without help from the conventional music industry

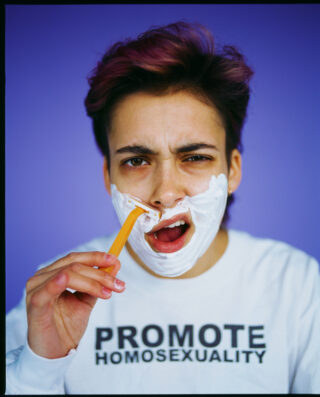

Lo-fi bedroom pop artists like Claud, Carpetgarden, Evann McIntosh and Smoothboi Ezra

Lo-fi bedroom pop artists like Claud, Carpetgarden, Evann McIntosh and Smoothboi Ezra

Remember the “transgender tipping point”? Way back in 2014, when the Brexit referendum was not even a glint in David Cameron’s beady little eye and the word ‘pinged’ was more likely to conjure up the image of an E’d-up lad in a bucket hat than a week of miserable isolation, TIME magazine declared that we were entering a new era of gender-diverse representation in popular culture.

Sure, okay. And then what happened?

While there has been an increase in transgender and nonbinary actors, musicians and writers in the public eye, it’s hardly what you’d call a flood. In many cases, the artists with the biggest mainstream platforms were already established before they publicly shared that they are trans or nonbinary – think global pop powerhouses such as Sam Smith and Demi Lovato, but also indie, rap, and punk musicians like Ezra Furman, Mykki Blanco, and Laura Jane Grace.

To come out as trans or nonbinary when you are already a known quantity can mean putting it all on the line, and is certainly no mean feat. But although there are a few musicians who have been open about their identity for more or less their whole careers – such as prolific popstar Shamir, who has publicly identified as nonbinary since at least 2015, the year his first album was released – if we are truly in a new era of visibility, then we should be seeing new trans and nonbinary artists coming up through the ranks.

Famously, though, progress in the music mainstream is slow going. Anyone who has seen the same kind of people dominating festival bills year in, year out can vouch for the industry’s problem elevating female or Black voices, for a start. Those campaigns have been going for years. Change creeps along.

So, in the absence of widespread structural change, marginalised artists get creative. They build their platforms in areas with DIY traditions and fewer gatekeepers, they utilise technology and social media to deliver direct to the people. If they are young and trans or nonbinary, it seems, they flock to the amorphous, ambiguous arena of bedroom pop.

Bedroom pop as a genre is hard to define. It’s Billie Eilish, yeah, but also girl in red, beabadoobee, mxmtoon and Rex Orange County. Like Eilish, plenty of the artists who started out making music at home or in DIY spaces cross over into mainstream success, but many others build dedicated fanbases online, avoiding industry input as much as possible. For gender diverse artists who want to speak candidly about their identities and experience, this can sometimes be the preferred route.

“For me, it’s the easiest way to approach music as someone who’s very anxious about these things,” says Evann McIntosh, whose 2019 single ‘What Dreams Are Made Of’ went viral on TikTok and netted them a strong following across social media. “It’s not [a community] where there’s a distinct idea of what you’re supposed to make, or what you’re supposed to look like, or anything like that. It’s coming only from you, and it’s got a very distinct audience because of how it’s only you.”

They’re not the only one who feels empowered by that independence. Carpetgarden, a bedroom pop artist whose tracks sweep up over half a million monthly listens on Spotify alone, presents the area they are working in as one with transformative potential, thanks to a lack of interference.

“Most people that do bedroom pop are just making shit in their bedrooms,” they say, “so they’re free to talk about whatever they want and put it out with independent distributors – there’s no say-so of what you have to write about. It’s made it a lot easier for artists to talk about real shit and real problems.”

This sense of openness, of intimacy, is characteristic of the genre. Part of this comes from the fact that many artists here are making music in their literal bedrooms – “It’s a safe space without judgement, and it’s just my process until I get to a point where I want to share it with someone else,” says Evann – but across the board it seems like bedroom pop artists are more willing to share themselves with others, not just in terms of gender identity or sexuality, but also when it comes to relationships, heartbreak and humour.

“I don’t really put a barrier up of what I talk about in my music,” says Smoothboi Ezra, the Irish artist whose lo-fi 2018 single ‘A Shitty Gay Song About You’ has racked up nearly seven million streams on Spotify. “I find it easier to be vulnerable than not.”

This openness extends to the artists’ relationships with their fans, too. Many bedroom pop artists are prolific posters on Instagram or TikTok especially, and many have strong Twitter presences where they interact with fans. Both Evann and Claud, whose indie-pop album Super Monster was released on Phoebe Bridgers’ Saddest Factory Records label this year, have public numbers for fans to text them questions, comments and anything else that crosses their minds, like a 21st century version of The Simpsons’ Corey Hotline.

“I think I am really, really honest and open about who I am online,” says Claud. “It was really, really great that I was able to reach people who are also genderqueer, or who understand what it’s like to be different in any sort of way. Then on the other hand, it’s like, oh my god I’m just a person figuring it out. Sometimes I feel like I’m twelve years old when it comes to my gender. I feel like a different person every day sometimes.”

It’s worth noting that trans and nonbinary people are a young demographic in general. While there are plenty of LGBTQ+ millennials, Gen X-ers and Boomers out there, the frequency of people identifying as not exclusively straight or cisgender has increased with each new generation. According to a 2021 Gallup poll, an unprecedented 15% of 18 to 23-year-olds in the US identify as LGBTQ+ in some form, with 1.8% of those surveyed indicating that they are transgender. This means that you are more likely to find gender-diverse artists in genres that skew Gen Z, just because of the balance of probability.

“A lot of bedroom pop artists are Gen Z so [from growing up with the internet] there’s a lot more social awareness, and a lot of progressive thinking,” says Carpetgarden. “A lot of people who make bedroom pop are putting progressive things into their music, and the Gen Z audience can take it in and it buries the stigma of a lot of things.”

The generational aspect can play into not just which themes bedroom pop artists are exploring, but also the way in which they are exploring them. Many of these artists began writing and releasing work in their high school years, and that combined with the hallmark openness of their work means that questions of gender and sexuality are often filtered through the lens of a coming-of-age. Speaking about their upcoming project Character Development, Evann, who is seventeen, says the release deals with “being a queer person in Derby, Kansas, in the middle of nowhere, and realising that I’m very fluid in a solid environment, and realising I don’t have to make myself digestible in that environment.”

Smoothboi Ezra reflects a similar sentiment in their 2020 single ‘My Own Person’, an introspective track that touches on the confusion and difficulty of being an LGBTQ person who doesn’t quite understand their own identity, and hasn’t yet made peace with that ambiguity.

“I wrote the song when I was sixteen, and I was very depressed. About everything,” they say. “I feel like within non-binary, I definitely fall under gender fluidity. I feel more masculine one day and more feminine one day, and I’ve kind of made a conscious effort not to understand it now. I think most of the upset and the confusion came from me trying to have a reason, and trying to understand it, so that’s where that song came from, it was me being upset that I didn’t understand myself. Now I’m kind of at a place where I don’t care that I don’t.”

Like Claud, Ezra has noticed their willingness to share has resonated with fans, many of whom may be grappling with their gender themselves. “I’ve had a few people send me messages saying my music helps them hear themselves in music where they hadn’t before,” they say.

For some artists, it’s important to represent an authentic experience for other young LGBTQ people. When releasing their recent EP The Way He Looks, Carpetgarden was hoping it could serve as a kind of beacon for other young queer people, and as a challenge to the heteronormativity of the mainstream music industry.

“Growing up, I did not have many queer people to look up to,” they say. “Being queer was kind of the unknown, and especially with how stigmatised it was for me growing up, it was this secret. [Now] there’s a lot more representation, and I think it’s good to have that representation be authentic, and from an actual queer person who has been through it, who has been called slurs and whose life is at risk all the time. I’ve noticed a lot with pop music lately, it’s kind of queer-baity. I think it’s good to have that authentic representation from someone who actually knows what it’s like.”

But it’s not all seriousness and deep exploration. Like its dialled-up cousin hyperpop, where performers can use vocal modulation as a tool to relieve dysphoria or invert notions of gender – a technique used by artists like SOPHIE, 100 gecs and others – bedroom pop as a genre makes space for artists to both give gender identity serious consideration, and also to play around with gendered expectations, to make jokes and exaggerate.

“There are some songs where I’m a little more playful, or a little more joking with gender or sexuality,” Claud says. “On my song ‘Guard Down’, it’s a little kitschy the way I pitched down my vocals. It’s clearly an octave down, or many octaves down. Obviously it doesn’t sound like a male rapper, but I thought it’d be funny to cosplay as one basically. And in my song ‘Ana’, with the lyrics ‘it’s been a pleasure to be your man’, that’s me playing with gender roles and so on. I like to have fun with it.”

This can be part of the appeal. There’s less pressure in working this way, making music in bedrooms and sharing directly with the fans, or working with small labels and independent distributors. The DIY approach and fluidity of genre, the lack of corporate interference and sense of community through social media all add up to a casualness that contributes to bedroom pop’s appeal among people who may feel locked out of more homogenous or prescriptive environments.

“I never started on any label. I really was just posting things on Soundcloud, and then Spotify, and going on Instagram the way I would usually do it,” says Carpetgarden. “I never had to put on any type of face or anything. Having that connection with the people who support me is cool, because it feels like I’m just posting on social media for my friends. I feel like a lot of bedroom pop artists are more friendly faces than celebrity artists. All these people are just normal people, writing about their lives.”