The story of E2-E4 – Manuel Göttsching’s accidental masterpiece

An improvised, one-track album that foresaw the coming of minimal techno as early as 1981

An improvised, one-track album that foresaw the coming of minimal techno as early as 1981

“I have a lot of tapes from these times,” says Manuel Göttsching on the other side of a crackly telephone line from Berlin. “A lot of tapes from the second half of the 1970s. I once released a series of CDs called The Private Tapes from a lot of the sessions I made around those years. But yes, something about how I recorded and produced E2-E4 in a way felt special.”

For many a proto-techno masterpiece, E2-E4’s release in 1984 felt like a left-turn even for one of Berlin’s most experimental musicians. “The newspapers said I have not understood anything in the modern developments of electronic music,” Göttsching says of the initial reactions from Germany. “They said I should better listen to Depeche Mode.” The Berlin Magazine apologised to Göttsching a decade later, saying they probably made a big mistake.

The piece itself (a single, continual track, 58:40 long) was recorded almost three years before its release at the end of a long tour, in one hour-long sitting with three humble intentions, none of them related to releasing music: practice, placating the post-tour comedown of no longer performing every night, and to give Göttsching something to listen to on an upcoming trip. As he says, he’d do this a lot, but this time was different.

The story goes that, having played a solo concert for only himself, completely on the fly, on listening back, Göttsching discovered that he had accidentally made the perfect record. The music flowed in total balance and even once he had played it over and over he couldn’t pick out any errors – even the levels were all they should be without his trying. “I listened back right after recording, and I listened to it quite often,” he says. “This was the end of 1981 when I was already working on a new solo album. This was not what I had in mind, but it was strange as there weren’t even any of the usual technical glitches such as distortions and level changes. I wanted to compose something more orchestral in this direction; this was just a session I’d recorded. I listened back and I just thought, ‘oh, not so bad.’ But that was more or less it… And then I played it to my friends who said, ‘wow this is great’.”

Inventions for electric guitar

Berlin in 1981 felt like the height of a cultural renaissance, where experimentalism in music was the new currency, and to hell with structure. Some people were writing twenty-minute compositions about knitting machines and typewriters, while others played Beethoven symphonies at various different rpms, all at the same time.

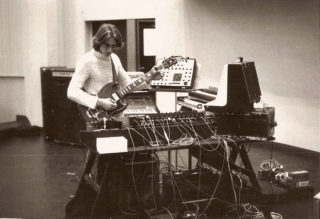

From Göttsching’s work as one of the founding members of pioneering space rock band Ash Ra Tempel in 1970, to the Rolling Stones covers band he played in at school, to his minimalist classical electronic album Inventions for Electric Guitar in 1975, to the now cult techno masterpiece E2-E4, the one constant value in his work has always been the freedom to invent. Ash Ra Tempel had been called the James Brown band on acid, flowing locks of hair obscuring expressions. They could play for hours without having written a note, and without needing to so much as look at one another. There was even a collaboration with the counter-culture LSD academic and psychologist Timothy Leary in 1972.

Göttsching speaks fondly of the sanctuaries others have found in his early compositions that have since led to many a krautrock and psychedelic exploration. Once he was part of the loudest band in Berlin – literally shaking the building of his first record label in a studio with no fades and an overly complacent engineer – but at its heart it was just the same principle as free jazz.

“I was trained in improvisation,” he says. “I started playing improvised music at the end of the 1960s with the first blues band – Steeple Chase Blues Band – later it was Ash Ra Tempel. The first Ash Ra Tempel album is completely improvised. I did a lot of mixing – sometimes improvisation and sometimes composition, but I like both elements. For E2-E4, I just took the instruments and prepared these two chords and some basic bassline, and then I started playing with it, improvising with the chords and the sequencers and the loudness of the chords so it makes a shifting event. I just played it.”

Where E2-E4 became a seismic start button for techno is in the second half of the hour-long track, where looped guitar noodling sits calmly on top of all the synthetic pulses of minimal electro. It was something that people would hear remixed in clubs in the ’80s, most famously becoming a staple of Larry Levan’s at the Paradise Garage in New York City (“I was a bit surprised people were actually dancing to it,” says Göttsching now. “I didn’t record it in the sense of a dance piece. The drums were very in the background, and it’s not really a ‘bom bom bom’ bass”), and yet it wasn’t a tone to alienate a classical audience, despite being an instrumental moment for rave, and a defining moment of analog production in electronic music.

“Originally I was a guitar player,” Göttsching remembers. “When I was a child I trained in classical guitar for many years, but I became interested, of course, in other instruments – in keyboards and synthesizers. I started not only to build my studio but also to collect more and more instruments. I started to compose for keyboards for my second album, New Age of Earth [originally released as Ashra in 1976], and then I started with different analogue synthesizers and sequencers. I built equipment that I used as one instrument. I just played every day and every night in my studio, recording sessions, and that was in 1981. E2-E4 was never intended to be a production or a new record, I just recorded a session like I’d recorded all the years before, and somehow this session was really great.”

A new game

It took almost three years for E2-E4 to be released. Virgin Records, which had been a very experimental label for young and untested music over the years was becoming more and more commercial. Göttsching’s contract with them was coming to an end, but there was an option to extend it. “I did not expect that this would be the right thing to release it on,” he says. “It was 60 minutes but at that time the CD was not a format, it was still only vinyl. How to make 60 minutes on a vinyl where each side only fits 20 minutes?” He laughs. “Just one piece and two chords for them? I thought maybe not. They would have bought it, sure, for tradition or old friendship, but I think it would have never seen the day.”

Nonetheless, the friendship still led Göttsching to Richard Branson’s houseboat, where he played him the piece. After all, Manuel was stuck with an odd problem: he had already begun work on his second album, setting aside a year for it to be made, grand themes and concepts and all. And now, by accident, he’d written, recorded and produced a faultless album in the space of an evening. Where did that leave him? Should this record be he second album? “Richard was not really anymore with the record side of the business,” he tells me. “This was now Simon Draper who ran the music part of Virgin Records. But I went to see Richard on his houseboat and played him a short track. He had a new baby and the baby fell asleep very soon. He said, ‘this music is perfect, you’ll make a fortune!’. Well, I’m not a businessman, but that was the language of Richard! Of course it was a compliment. It was a statement which said I should continue to work with this piece and get it released somehow and spread it all over the world.”

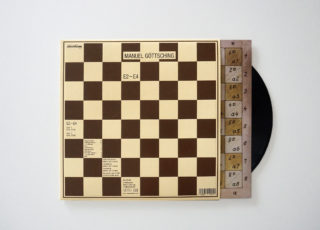

Still, Göttsching dwelled on the recording for the next two years until a friend of his told him he was starting an independent label and would love to release something with him. Manuel titled the piece E2-E4, after one of the most common moves to start a game of chess, and it was out.

“The funny thing is, it’s one of the very few cases where I had a title but no music in the beginning. The title came up when I was working with the first home computer – I had an old Apple 2 and I was starting to write programmes with it. You get used to the simple programming languages and commands like hex numbers and html systems. The other part was, ‘ok this looks very much like a chess game, when you have numbers and letters to dictate your next moves’. E2 to E4 is a very simple opening for any chess game. But it could also be written as a kind of programme for a computer.

“Oh, and the other influence on the title was the first Star Wars movie that had just come out. This little robot was called R2-D2, and R2-D2 could also be a programme. It’s just a good title for a music track that I wanted to use one day. For me this recording was opening a new game. It was also the first record I put my own personal private name on; it was not released as Ash Ra Tempel or Ashra. Ashra always had this connection before, because I wanted to keep a little remembering it of it all. I’d used it as a pseudonym for my solo records, but this time I didn’t use it at all.”

The album artwork also replicated a chess board. “I insisted that nothing was written on the back of the original cover,” he laughs. “You can actually use it as a chess board if you liked.” I ask him if he’s ever played a game on the album sleeve (of course he has), and if it has the same effect as playing a game of football at your home stadium. The advantage of familiarity. He’s modest in his reply, but I’m sure he always wins. “I’m a good chess player,” he tells me. “I’m not as good as my father was, though. He trained me when I was young. We played a lot, especially end games and specials – when you don’t have so many figures and it’s a game of tactics. My father could actually play with just the numbers and the codes in his head; he could do a whole game without having a chess board in front of him.”

As for now, Manuel Göttsching and his wife – a well known film director – have set their minds on a re-working of E2-E4 for the ballet. Collaborating with the director of the Berlin State Ballet, Gregor Seyffert, they have found some games of chess that have been archived from the 1890s and 1900s that lasted roughly an hour. The aim is to recreate a match on stage with a special LED-lit chess-board floor, while Göttsching plays the music behind the dancers. His eight-year-old Leonard is a good dancer, too, he tells me. “And I’m teaching him classical guitar. Of course he wants to maybe play some rock’n’roll or some rap, but we’ll have to see about that.”

As legacy goes, maybe this album is enough, though. Its revival in recent years is testament to that. “E2-E4… It was just another thing,” he says. “I feel like an inventor. I like to see myself as someone who invents music, and this was perfect.”