The Rates: Divide and Dissolve shout out artists beyond borders

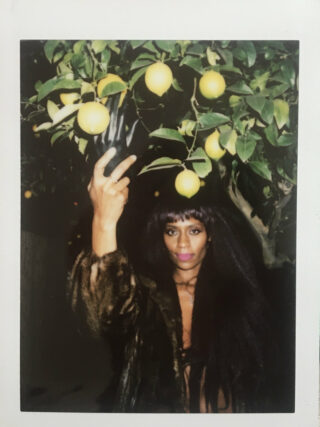

Takiaya Reed of the Melbourne doom duo talks us through the artists she believes deserve far more credit than they get

Takiaya Reed of the Melbourne doom duo talks us through the artists she believes deserve far more credit than they get

“This feels like what needs to be happening, and that’s how I’ve always approached music. It’s literally a feeling.” Takiaya Reed is talking about ‘the drone’, a style of playing music that seems almost instinctual or elemental to anyone who picks up an instrument. For her, it was a guitar, with which she has since mastered the art of the abyssal rumble. “Heavy” only begins to describe the music she makes with drummer Sylvie Nehill as Melbourne duo Divide and Dissolve, not least because of its largely unspoken subject matter. The feeling of their latest album, Gas Lit, is one of crushing protestation against systemic violence, played out in body-enveloping doom and sludge. But when guitarist Takiaya Reed was asked to put together a list of ‘underrated’ musicians for this feature, there’s a noted absence of anything by Sunn O))) or Sleep – two reference points for the atavistic type of metal Divide and Dissolve appear to make. In fact, among the folk, industrial EBM and hip-hop, there’s no metal at all.

I ask about this. “Oh my God, genre can feel so oppressive,” she says. “It’s there to separate simply because of like, literal bpms or something.” The idea of ‘false metal’ is so pervasive among the hardcore members of the subculture that even Weezer named an album after it. Correctly, Reed doesn’t give it the time of day.

“It’s funny, if I were billing myself for a show, I would play with every single one of these artists, and I think that would make a lot of sense. I personally don’t want to impose any borders. At the end of the day, music is just energy that’s out there.” Reed speaks about music with an almost oracular, mystical intonation, but her arguments are grounded in a complex problematisation of history and colonialism, the effects of which overtake how we view reality, even down to something as purportedly apolitical as genre. “Who even invented these gatekeeping colonial constructs?” she asks.

In the spirit of breaking boundaries, our conversation loops around on itself, touching on racism, fascism, ethnomusicology and, above all, the importance of celebrating music. We don’t talk for long before Reed launches straight into the first of her new artist choices.

Dafydd: How did you approach putting together this list of artists?

Takiaya: Basically, I was hanging out with my friends and we wondered, what’s up with these amazing artists in our friend group? She reminded me of this amazing artist, Jasmine Infiniti. She’s so incredible. I’ve seen her DJ before. She just nurtures and nourishes the scene that she’s a part of, and also all the people that happen to like her music. It’s transformative and incredible.

D: That’s so cool, she’s someone on the scene who’s keen on getting people hip to it. She has a record label, right?

T: Yeah, her record label is called New World Dysorder. I feel like her stance is just “no boundaries” – no overall colonial borders or anything, because music is amazing. It can travel and influence people. I feel like she helps facilitate literal life. My friend Adonis and I were talking about how nice she is. I’ve only met her a few times, but every time I’ve seen her, I’m like, you were so nice, and literally changing the world. The frequency of it is manipulated by her existence in the most beautiful way.

D: So she first came to mind when you were thinking of people who are perhaps generally underrated, or overlooked by the wider world?

T: I don’t even know if she really is underrated, but I would say that. She definitely needs more attention because she’s doing so much amazing work out there.

D: I wrote a bit of ad copy for BXTCH SLÄP [Infiniti’s debut album] for a record site. I was really bowled over by it!

T: Oh, yeah, it’s absolutely legendary, beyond 100%.

D: For this feature, I think generally people pick artists who’ve had some kind of shaping force in music and art. It occurs to me that the first of the three older artists that you’ve chosen are really people who introduced something brand new and went on to inspire so many different musicians. But then, on the other hand, a lot of their style and approach has since become commodified and whitewashed by the music industry. That’s what came to mind when I saw that you’d listed ESG.

T: Yeah, totally. When I think about ESG, I think whoa, how are they not one of the biggest bands in the world? Because they certainly are one of the most sampled bands in the world.

D: Yeah, for sure. How did you first come across ESG? Did you hear them sampled first?

T: My punk mom, Osa Atoe, told me about ESG and played their record to me ages ago. I instantly felt a connection because of having learned about their story documented in her zine Shotgun Seamstress.

I’m just reflecting on that now. I obviously feel upset by such systemic invalidation and ignorance. It was hard to only choose three older artists because there’s so many people out there who go unappreciated — and then as far as ESG are concerned, they are an institution as well.

I don’t know – it makes me want to continue talking about people’s music. It’s important for us to all support each other. I don’t want this to be a precedent where people have to get old and die before they become recognised.

There’s obviously a systemic pattern around all of this. But I’m also so grateful for these musicians. Which is why I also chose Beverly Glenn-Copeland.

T: It’s heartbreaking that he wasn’t recognised until years, if not decades later. But I’m gonna move past my heartbreak and look forward. That’s the theme of the three newer artists and three older artists. All of them are the same in that regard.

D: I’m so glad that you picked Glenn-Copeland. I love that compilation album so much. I hadn’t realised that I’d heard ‘Ever New’ somewhere before, but properly listening to it at three in the morning brought me to tears. It’s incredible how he’s become more widely known lately. Where did you first come across his work?

T: My friend Tashi Dorji played us his music for the first time while we were on tour together. It felt like a blessing. Glenn-Copeland changed everything. The world as we know it was literally a different place when he decided to share his magnificence. He is amazing and deserves to be recognised. Literally a living legend. I’m so grateful.

D: That’s an interesting choice of word, ‘grateful’. What do you mean by it?

T: I’m so grateful he is alive, and our elder. His music is incredible and weaves together stories that need to be shouted from the mountains. He has created an extremely significant body of work that must be memorialised.

D: There’s so much music there too, especially for someone who went decades without releasing music. He touched on so many things, from folk to new age and ambient. Why do you think it took so long for him to get the recognition he deserved?

T: Due to systemic inequalities and tragedy.

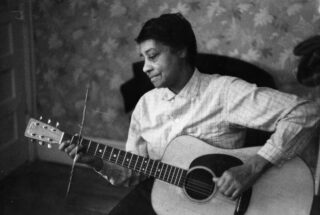

D: Tell me about Elizabeth Cotten. I’m a big fan of finger-picked, ‘American Primitivist’ music but I’d never heard of her.

T: Another person who changed everything!

D: I was looking at her Wikipedia page. She was born at the end of the 19th century, and then lived to be almost 100. Did you know that she wrote ‘Freight Train’ when she was 11 years-old?

T: I didn’t know she was 11, that’s incredible. I love that song ‘Ain’t Got No Honey Baby Now’, and ‘Going Down the Road Feeling Bad’. My Gosh, the capacity of her music to understand emotion…

D: I think it’s the straightforwardness as well, right?

T: Yeah, it holds so much space. It’s immense.

There needs to be a systemic shift around the field of ethnomusicology. Because white people discredit people like Cotten from a formal academic perspective. The contributions of these musicians! It’s an incredible violence, and it’s reinforced by academic institutions and the industry. Oh, you exist so these people can copy and take all the credit. That’s unacceptable. So we need to continue talking about it and opening up spaces for conversations.

D: And particularly in Cotten’s case. I think there is a sort of commonly held idea that her style of finger-picked guitar was the invention of white Appalachians at the turn of the century.

T: [laughs] that’s such a scam.

D: I know! Think how massive country music radio is in America, and how it’s predominantly viewed as music by white people for white people.

T: And obviously, Black people invented country and soul. And rock and roll. And house and techno and hip hop, and R&B.

D: It’s basically global. All of the stuff that people around the world enjoy. I was gonna say, you play guitar in the same way as Cotten – and Hendrix, for that matter. Left-handed, upside down?

T: Yeah, I was handed a guitar and I just flipped it upside down and turned it around. I was like, okay, that feels better. I didn’t even know there was such a thing as a left-handed guitar. I thought, oh, you can’t play it this other way? That’s very strange. So I figured it out. But this feels ergonomically correct.

D: I remember learning the guitar as a kid. I’m right handed, and somebody handed me a left handed guitar. I thought simply, I should not play this. This is playing it wrong. Looking back now, it seems kind of silly.

T: It’s not silly, I understand how that can happen. I wanted this modification on my guitar just so it’s easier for me. One day I’ll get it where… you know that switch on a guitar?

D: The tone switch thing?

T: Yeah, I’m always hitting that thing because of where it is. It’s not that big of a deal. But I’d flip it upside down. That’s the only thing I think is different in playing a guitar the way I do. I am glad that nobody ever told me not to play this way though. I just have to do it the way in which it feels good, and makes sense. And then someone saw me playing guitar and said, hey you play like Elizabeth Cotten, who I weirdly knew about already.

T: I’ve had the pleasure of getting to know McKinley Dixon. Being around him as a friend, I am constantly taken over by how brilliant he is. His music is profound. The flow, the energy, the gracefulness around it. He moves like the ocean. It’s incredible.

D: He’s also done a lot of stuff. I feel kind of ashamed that I haven’t heard of him, really.

T: I’m glad you have now.

D: Did you guys play any music together? Did you come up in the same scene? I wouldn’t have thought a rap artist and a metal band would work [see: Limp Bizkit].

T: We played a show before. That was really cool. I would say that McKinley and Divided and Dissolve work within the same theme, if you can call it that. It seems perfectly reasonable, and hopefully something happens in the future where we go on tour together. I just love being around McKinley. He has influenced us quite a bit — and he will continue to make a tremendous impact on the world.

D: I saw that he has an album coming out soon, For My Mama And Anyone Who Look Like Her.

T: I know! I can’t wait for him to blow up.

T: Zero Charisma is also one of my friends. Her music is profound too, and really had an impact on me. She’s also Black and Cherokee so I feel this kinship towards her. I’m just so grateful.

D: I was curious about who Zero Charisma was because I couldn’t really find all that much information about them. There are two tracks on Bandcamp.

T: The ways in which she utilises her voice as an instrument, and many other instruments, is incredible. I would say she is another person who has a really positive and important impact on the scene. She’s an extremely community-minded person. And she does so many amazing things for so many people all the time. I’m filled with a deep appreciation and joy.

D: I must say, it’s nice to be writing one of these things about people that the artist knows personally. It’s a useful way of going about the brief.

T: There’s just so many people out there doing so many incredible things for their community. How sick would it be to give this person a gigantic platform? You continue to spread their compassion and love towards more people. So yeah, she’s amazing. I can’t wait for her to blow up as well.

D: I think also these pieces can provide some small counter-‘canon’ against the established greats of music.

T: Violences have been enacted with the study of music, but people have created healing with the study of music as well. So it just depends. It goes back to what I was saying about music being something that’s ‘out there’. Music has always led movements, be they hateful or loving. People feel a connection to music; that’s what people go to war with.