Squid: The joy and unity of making a strange, bleak debut album

The Bristol post-punks on Bright Green Field and how it feels for your generation to be absolutely fucked

The Bristol post-punks on Bright Green Field and how it feels for your generation to be absolutely fucked

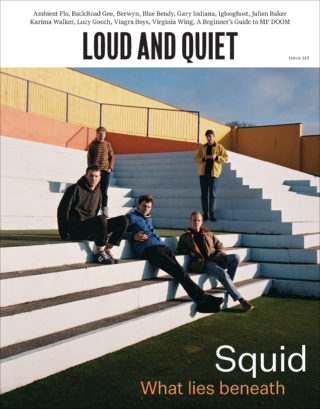

Squid are on the cover of Loud And Quiet Issue 145. Grab your copy, or become a member to support independent music and journalism, here.

Squid’s singing drummer Ollie Judge was seven years old when 9/11 happened. Like many generations of British people before him, war and catastrophe was something that became a background part of day-to-day life. Although his parents’ generation may have been terrorised by the threat of nuclear annihilation – practising safety drills of hiding under tables in classrooms, receiving pamphlets through the door about radiation fallout, and seeing it unfold in harrowing dramatisations on television via films like Threads – the relentless televised coverage of 9/11 and the ensuing War On Terror was new terrain.

“After 9/11 I was terrified of being bombed,” Judge tells me. “It made me an insomniac for at least two years. I’d lie in bed and read and if I heard a plane go overhead I’d go under my covers and just be like, ‘Alright this is it. We’re getting bombed now.’ I’d have to try and imagine all the people on the plane going on holiday.” Believing this to simply being part of normal life because he knew nothing else at such an age, it wasn’t until years later that Judge began to unpack this experience and how it had burrowed into his psyche. “Having what I now realise was really bad anxiety at such a young age particularly struck a chord with me in 2020,” he says. “I can’t imagine what the pandemic is doing for the mental health of young children and that thought is what brought me back to write about those intense feelings of anxiety.”

This experience was the foundation of one of the songs on Squid’s debut album; a track called ‘Global Groove’. The lingering anxiety from childhood mushroomed when Judge was watching a documentary. “After watching Adam Curtis’ Hypernormalisation I started thinking how we’ve become numb to violence and death through televised wars,” he says. “The ending to ‘Global Groove’ features a story that I told into a dictaphone. This story is broken up by segments of television presenters laughing maniacally as if someone is flicking between TV channels.” It was something Judge felt a glimmer of himself after he finished Curtis’ documentary. “I watched that and it was incredibly harrowing and it was just before bed and I was like, ‘Oh god, I can’t get to sleep now,’” he recalls. “So I just watched an episode of The Simpsons and everything was fine. It was like: ‘This is fucking awful. I’ve just watched people dying and now I’m watching The Simpsons and everything’s okay.’”

This is a perfect distillation that embodies the experience of young people who have grown up in an almost exclusively digital world, where the endless scroll of online life blurs the boundaries of sincerity and irony, death and comedy, tragedy and farce – and in the process, as Judge points out via Curtis, it can lead to a numbing sensation of life’s most extreme events whilst still being hyper-aware and emotionally strangled by them. Given the generation that Judge belongs to are often mocked and denigrated by an older generation (one often obsessed with a war they played no part in) it’s interesting to reflect on how little is spoken or thought about the impact on children being brought up in the era of the 24-hour news cycle during endless wars and conflicts. Easier for them to thoughtlessly bang on about young people being spoilt because they have smartphones and fancy coffee, I suppose.

While this subject matter might feel like an unexpected shift or drastic escalation in tone from previous work, there has always been a tension and sense of unease creeping into Squid’s music and lyrics – it’s just largely been buried under how infectious and fun a lot of it is. It’s easy to forget just how intense, twitchy and wonky their knockout single ‘Houseplants’ is, such is its endlessly propulsive groove and catchy skip. Yet Squid have always been very good at submerging the weird within the accessible, working in experimental and unpredictable characteristics to music that 6 Music Steve Lamacq dads can happily nod along to on the radio after Blur has been played.

Often unfairly lumped in with the crop of modern post-punk resurgence bands, many of whom seem interested in little else other than mimicking Mark E. Smith, Squid have always been a much broader outfit. Their output of post-punk-funk-rock-kraut-jazz feels more in sync with the wild energy of Ohio outfits like Devo and Pere Ubu than any of the 1970s UK moody raincoat crew.

Their debut album is called Bright Green Field (coming May 7 via Warp Records) and very much feels like a continuation of their trajectory to date, albeit with even greater emphasis on the experimental side. Perhaps not as many easily digestible bangers to gulp down for the 6 Music dad squad. “We’ve ended up making a really fucking weird record,” Judge told DIY magazine, and despite having an amazing run of singles in recent years (‘The Dial’, ‘The Cleaner’, ‘Sludge’ and ‘Houseplants’) they’ve opted for all fresh material on their debut. “The album had to speak for itself as a whole,” Arthur Leadbetter tells me, who makes up the band along with Judge, Louis Borlase, Laurie Nankivell and Anton Pearson. “To do that we couldn’t include songs from the past. They’ve had their life and we’ve moved on.”

Their debut album is called Bright Green Field (coming May 7 via Warp Records) and very much feels like a continuation of their trajectory to date, albeit with even greater emphasis on the experimental side. Perhaps not as many easily digestible bangers to gulp down for the 6 Music dad squad. “We’ve ended up making a really fucking weird record,” Judge told DIY magazine, and despite having an amazing run of singles in recent years (‘The Dial’, ‘The Cleaner’, ‘Sludge’ and ‘Houseplants’) they’ve opted for all fresh material on their debut. “The album had to speak for itself as a whole,” Arthur Leadbetter tells me, who makes up the band along with Judge, Louis Borlase, Laurie Nankivell and Anton Pearson. “To do that we couldn’t include songs from the past. They’ve had their life and we’ve moved on.”

The album came to life with the song ‘G.S.K.’ and began to take shape and form from there. Referring to the pharmaceutical company GlaxoSmithKline, Judge found himself staring at the HQ building one day and got sucked in, vortex-like, to an imaginary world that unfolded around it. “I was on a MegaBus from Bristol to London,” he recalls. “It was the day we were supposed to withdraw from the EU and I was reading Concrete Island by JG Ballard. The news was coming in and I was going over the flyover and everything was just so horrible. The idea that we are living in a complete dystopia at the moment settled in.”

This was something that chimed with him even more due to recently reading the work of Mark Fisher on hauntology and lost futures. “I started writing down what was going past me,” he says. “I imagined being the protagonist in a modern day Concrete Island, looking up from underneath the flyover and seeing businessmen, new developments covered in netting, discarded rental bikes, a proper real-life dystopia. It really clicked and set the tone for the rest of the album. Then it kind of spiralled out of control and just made me think about things that had already happened but were incredibly dystopian.”

However, despite being Ballardian in tone, both musically and lyrically, Bright Green Field isn’t a concept album, nor is it a warped reflection of the strange and unravelling times we find ourselves in during the pandemic. “It’s not usually a conscious decision to write a song about what the world is doing,” says Nankivell. “The way we compose is much more about listening to each other musically. Whether that’s been influenced by the world is usually a subconscious thing rather than being: ‘We’re gonna write a song about climate change, Brexit or Donald Trump.’

“There is a sense of real uncertainty and bleakness but it’s certainly not being reactionary to a microcosm of bad stuff going on. I think it’s kind of unspoken that the music we’ve been making has ended up having an atmosphere of a certain sense of dystopia. The new music just happened to pre-empt a certain feeling.”

Nor would the band go as far to call this a political record, despite it touching upon socio-political terrain. “I’m always kind of reluctant to describe our music as political,” says Judge, who writes the majority of the lyrics. “I’m not educated enough to be this kind of mouthpiece. I feel I’d be doing people a disservice. I’m definitely not the bastion of the disenfranchised youth. There are always going to be political references but it’s not the main talking point.”

What Squid would call the album is something of a coming of age record, with that period of quite profound and intense change that can come as you hit your mid-twenties and begin to reflect on things and see things changing all around you. “A big thing was definitely seeing friends really quickly achieving a lot of what they wanted to achieve in a short space of time,” Borlase says. “And then seeing the changes of lifestyle. It’s kind of a coming of age record but it’s also a kind of coming to terms album – more around the awareness of the reality that we’re living in.”

As a group of young musicians living in Britain right now, the band are undeniably part of a generation that has inherited a pile of shit plopped squarely onto their plate to stare down at. Despite Judge’s claims that he’s no political mouthpiece, he becomes quite animated on this. “There’s no question that we’ve been completely fucked over at every opportunity,” he says, “but I feel like we’ve been living with getting fucked over for ages. I always track it back to the university tuition fees issue. In my eyes that’s when it all started. I hate to say it but we’re almost desensitised to just how much our generation gets fucked over on a daily basis.”

One could quite easily argue there’s grounds for complaint here, despite the band being keen to point out how lucky they are in the grand scheme of things. As a heavily active touring band prior to lockdown (Squid are almost defined by how much they play), and with the entire industry clinging on by a thread via the government’s callous indifference, further news about lies and catastrophes over European touring visa issues post-Brexit are clearly going to impact on the band in the long run. “There’s a lot of anger at the minute around the news about the UK touring industry,” Pearson says. “They’re fucking snakes, man. The situation isn’t great and it’s all just an ongoing tarnishing of the way you feel about where you live. There’s a dark cloud over the British Isles that is hard to see going away anytime soon.”

However, despite some of the conversation around modern life in Britain understandably veering towards the sour, the album they’ve created during this period was one that a great deal of energy, intensity and joy went into. When lockdown measures eased over summer, the band got together and holed up for five weeks to write the album. They then connected with their long time producer Dan Carey to record it in his modest studio in London. “It added this intensity to the process that you would never normally get because they’d had all this time living together just playing over the set,” Carey tells me on the phone. “We spent a couple of days setting up so that we had this perfect sound in the room and then they just played the whole album. I couldn’t believe it – it was just amazing to hear all these songs properly for the first time. They had done lots of work on the dynamic flow of the record. Sometimes when you’re recording new material there’s a slight uncertainty over what’s happening but there was none of that. Everyone knew exactly what they were doing.”

So, how do the band all land on the same page given that there are five of them, they instrument swap, share lyric duties, and seemingly operate as a cohesive unit? “It’s like any decision, we have to just trust each other,” says Leadbetter. Pearson adds: “Artistic and creative ownership is split equally. Nobody has had to compromise; it’s been an amazing, shared project.” For Borlase, letting go is as important as what comes out of the end result. “It’s been really important for us not to be too attached to a certain idea,” he says. “It doesn’t need to be an assumption that lyrical content or a certain specific musical approach is unanimous. I like the idea that there’s still a large amount of interpretation that takes place between us. This music means something slightly different to each of us.”

From an outsider’s perspective, Carey backs this up. “What’s really lovely about them is that they give consideration to every single idea that anyone presents,” he says. “So there’s no sense of hierarchy or ownership. Everything gets examined. Often with bands that are super democratic it leads to indecisiveness. Usually I think it’s better when there’s someone who kind of just pushes it along and it’s like their band, but somehow with Squid they have completely nailed the way of just being able to kind of co-own everything.”

Carey has a reputation for creating a unique atmosphere in the studio. For his Speedy Wunderground singles club recordings he insists the song is completed in a day, there’s no lunch break, the lights are turned off and lasers and smoke machines are turned on. For this recording Squid were working in the middle of a heatwave. “I don’t think I’ve ever been to a gig that hot let alone a recording session,” says Pearson. “The air con was turned off because it would make noise. You’ve got all the amps, the mixing desk, the bodies, literally everything in the room was a heater. We were just dripping with sweat and playing furiously. At some point we became slightly delirious.” Guest saxophonist Lewis Evans, of Black Country, New Road, would step up to record his parts and every time his sax would be out of tune due to the melting heat. “It makes me wonder if Dan was just thinking, let’s make them sweat,” reflects Nankivell. When I put this to Carey he just laughs and offers up a “maybe”.

The result is an album that is very much a complete piece. The band didn’t just focus on individual songs and would often rehearse playing the entire album, and the decision to avoid earlier singles was the right one. Ironically, for a band with such a set of distinct and singular previous tracks to their name, their inclusion would have been a jarring distraction. Instead songs like recent single ‘Narrator’ – featuring Martha Skye Murphy – unravel over nearly nine minutes of agitated rhythms, overlapping vocal melodies, immersive sound design and utterly unpredictable tonal shifts before bleeding into the slick melodies and spiralling guitar groove of ‘Boy Racers’ to create a world that feels both disparate and interconnected. Which makes sense given the album is rooted in the idea of imaginary dystopian cityscapes, as what could be a more accurate depiction of a fractured yet inherently connected place than modern city life?

Bright Green Field operates on both a micro and macro level, sometimes zooming in on details and real-life people and at other times pulling back to examine wider issues and themes. The closing ‘Pamphlets’ – which unfurls like something from In Rainbows-era Radiohead, albeit with a more angry and aggressive charge – imagines a person getting their only source of news from right-wing propaganda pamphlets. ‘2010’ simultaneously addresses London’s housing crisis and the mental health of an individual slaughterhouse worker.

‘Documentary Filmmaker’ is an example of this dual microscope and telescope approach. “It was written about a loved one who was admitted to the Phoenix Ward of St Anne’s hospital with anorexia,” Judge says. “It’s the same ward that Louis Theroux visited in his documentary about anorexia. I used to visit the ward most days and walked past a photo of Louis with the hospital staff. They’re all looking really happy in the photo and then you look around and everyone is just really sad. It’s a weird contrast of that picture and what actually goes on on the ward. I imagined that Louis was there every waking moment, for months and months, with the patients experiencing their time on the ward in extreme realism.”

It’s not an explicitly personal song and the lyrics remain cryptic, nuanced and coded, but it comes from a place of emotional turmoil in Judge’s life. “It was nice to see that person getting better on the ward but it was also quite a horrible way to spend most evenings,” he says. “Just seeing a lot of people on the wards that are kind of beyond help. Seeing people that have given up hope and have come to terms with the fact that this illness will kill them. Anorexia has the highest mortality rate of any psychiatric disorder in adolescence.”

The band’s ability to digest and distil such a broad range of ideas, themes and topics makes Bright Green Field a bold and ambitious debut. One that is unafraid to take risks and keen to avoid coasting on previous successes, even if it’s resulted in some slight anxiety about putting it out into the world. “I’m a complete worrier,” says Judge, before Borlase adds: “And I’m a complete panicker. I’ve had bad dreams about negative reviews. I listen to the album occasionally and just think there’s so much in here to either love or hate.” While they have tried to ignore the fact they are something of a buzz band, from BBC Sound of 2020 Poll to a record deal with Warp within a year, it is something that trickles into their thought process. “People tend to be a bit more critical with hype bands,” ponders Judge.

On paper Squid and Warp records may initially seem an unlikely pairing, given the label’s history of being synonymous with a lot of electronic music, but the band’s post-genre and experimental approach is a snug fit. “When we got the Warp offer it was a bit like, ‘Oh that’s weird,’” says Judge. “But it kind of makes sense. It wasn’t the most obvious choice but it kind of is at the same time. I’ve also been a fan of Warp since I was really young. We used to have a lodger at my parents’ house and he was super into Aphex Twin. I remember him giving me Come to Daddy and being absolutely petrified.”

The process of making this album has helped solidify a sense of identity in the band, too. “When you first start a band you just want to be a band and then as you progress you start to ask yourself what kind of band do you want to be,” says Leadbetter. “I think we started to realise what we want to do is to be in a position where we’re comfortable enough that we can just have as much fun and make whatever music we want. That means that we’re able to do things like this album where things are kind of drastically different.”

Despite some members worrying about how it may be received, there’s a natural confidence in the band in what they’ve created their debut. Leadbetter, who is endlessly positive in conversation, is also thrilled he managed to get his dad on the album. “He’s a professional musician and researcher,” he says. “He specialises in medieval rock and renaissance instruments, so he played the rackett on the album. Which is a bit like a squashed bassoon. We had this idea to layer him alongside the synths to create this mega drone.” There’s also a number of guest vocalists featured, although true to Squid’s form they appear in such a mangled, treated and distorted way that they aren’t recognisable.

With the UK currently in a state where normal service is far from resuming any time soon, it leaves the band in a position where a typical album launch and supporting tour aren’t really possible. Bizarrely, the subject that kicked off the tone and feel for this whole album – the GSK building and pharmaceuticals – is one that Judge is sort of thinking about again, albeit in a different context. “I always like looking at weird merch that bands do,” he says. “I want to do a limited run of vitamins to keep people’s immune systems up.” The band have found a website where you can design and construct your own vitamins. Squid’s very own medicine. “We’re going big pharma,” Borlase declares with a laugh.

Despite the bleakness that currently surrounds so many of us, and with much of it permeating through the mood of this album, Squid are feeling hopeful and optimistic. “If this climate keeps taking a downward trend our music isn’t going to keep descending into the pits,” Leadbetter says, but then stops himself for a moment and asks with a laugh, “or maybe it will?”