The limitless persona of Rejjie Snow – the Irish rapper writing his life story at 23

Alex Anyaegbunam comes from a place where kids don't end up on a record label with Young Thug

Alex Anyaegbunam comes from a place where kids don't end up on a record label with Young Thug

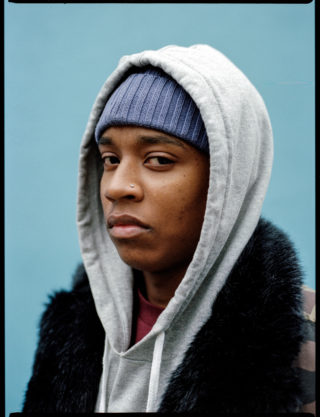

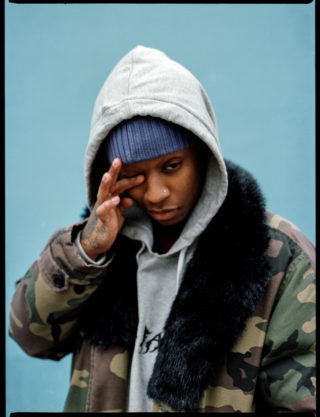

Rejjie Snow is talking about his allergies. He’s sat on a bench by a bike shop in front of a wall plastered with posters, slogans and community notices, a short walk from his home in Elephant & Castle, south London. A white cat with pink eyes and a charming arrogance strolls into the shot as Rejjie’s having his photograph taken. “I love dogs, but I’m allergic to cats,” he says, in a thick Irish-American accent, “they give me the sniffles.” There’s something both amusing and unexpected about hearing this deep-voiced, athletic, tattooed rapper use the word “sniffles”. But in a way it sums up the 23-year-old from Dublin. Having spent a couple of hours in his company on two occasions he comes across as a sensitive, mild-mannered, honest guy, both proud and unashamed of his roots. In other words: if you’ve heard tracks like ‘D.R.U.G.S.’, in person he’s maybe not what you might think.

It’s a bracing cold January afternoon. Outside on the street, the rain turns to sleet turns to sludge. Rejjie walks into a modern cafe serving strong tea and playing reggae on the soundsystem. He keeps his coat on, the spiderweb inked on his neck visible from underneath his beanie. We’d met a fortnight before, in the even chillier surroundings of Groningen, a university town in the north east of the Netherlands. He was performing at Eurosonic festival, an event programmed early in the year, where festival agents from across the continent travel to watch new artists play and book them for their summer line-ups. The morning after his show, I took him record shopping for Loud And Quiet’s web-series Bands Buy Records. He bought some jazz, hunted unsuccessfully for some rap, and came away with a Billy Ocean record as a present for his mother. As I left he was searching for a local place to buy some dutch hash brownies. “I ate them before I got on the plane home,” he says today, recalling it with a wise smile, “they were pretty good.”

Alex Anyaegbunam is a child of the early ’90s’. Born in Dublin he grew up in Drumcondra, on the north-side of city. With an Irish mother and a Nigerian father he has a brother and a sister (who he doesn’t get on with as they’re “total opposites”). As a youngster he’d spend lots of his time at his grandparents’ house. Along with his dad’s music collection, that’s where he first came into contact with the sounds of jazz and ska. The classics: Bill Evans and Miles Davis. But back then he wasn’t going there for that, even if they were subconsciously filed for later years. His other male cousins would be there and they could play football. At school and around home his friends were just mates because they were local. He was outgoing, sporty and “a bit of a terror,” but there was always a nagging sense of his difference.

“I always knew I was different to everybody,” he tells me. “I was always reminded of that, too, everywhere I went. I’d put on a brave face everywhere I went. I’d always try to be sociable, but as soon as I went back home I’d be asking my parents all these questions.

“The area I lived, for whatever reason I was the only coloured kid. I just had a hard time at school. Not a hard time… just in the sense that I’d have to explain a lot of things and people would say things to me and I wouldn’t know why. I’d always see myself as the same as everyone else – I didn’t see colour.

“Because of that I feel like I’ve got too much patience these days. It’s not such a bad thing though, is it? I’m very open to people. That wasn’t always the case, I used to be a bit of a hot head.”

All the while music was in the background, but that changed with a couple of key moments. First was his football coach who’d drive the team to games pumping out the motivational sounds of Queen on the bus stereo. “I just love that shit, so raw and aggressive. I wish I could make music like that,” he says. The second was his choice of company. In his early teens he noticed the tags and designs of schoolmates doing graffiti on desks and walls and he liked it.

“Meeting that graffiti lot… I wouldn’t say it saved me, but it kinda guided me into an area,” he notes. “The culture itself was a big catalyst. I never looked back.”

Beyond the art, his new passion would become the introduction to the music he’d eventually make. Nas, Wu-Tang, MF Doom. As this education from his peers in hip-hop continued to deepen, a broader fascination with American culture took hold. At 17 it was realised. He left school in Dublin and enrolled in a scholarship playing football (soccer) at a college in Florida. It was, he says, a bit of a free pass. He’d already decided by the time he was 15 or so that despite being a promising player he wasn’t aiming to become a professional. Still, the bursary meant he could go to the US, train in the day and fill his free time with other stuff.

“I woke up at 5am everyday for training. It taught me discipline,” says Rejjie. “Even now I treat my music – the hip-hop, the rap, whatever – kind of like a job. I’m quite punctual, I try not to be late or miss shows. I’m grateful for the opportunity to get paid to speak, essentially. I try to just treat it the same as college or something.”

After 18 months at high school, he transferred to a university in Savannah, Georgia. His mind by this point was almost entirely off football, instead feasting on the free courses on the timetable – sculpture, graphic design, painting – as he made music on his laptop at night. Still though, he felt like a bit of an outsider. “My music, I think it was online then, some people knew about it, so I felt kind of like this weird kinda guy on campus.”

Home was like a magnet though, and he decided to return. He’d had some success with posting his music on the Internet, to the extent that when he’d visit Dublin those people who weren’t begrudging his achievements would want selfies and conversations. It left him feeling a bit “weird and embarrassed” and, for a while, doubting whether music was the right plan at all, until he started afresh, chose London as his permanent base and came up with the name Rejjie Snow. “I was like” ‘I could do so much better than that.’ I had to reinvent myself.”

He made friends quickly. In particular Archy Marshall aka King Krule, and each weekend they’d mess about, freestyling tracks at Archy’s place. “He’s definitely someone who I pay a lot of respect to in terms of how I approach my music,” Rejjie tells me. “He knew all this hip-hop shit too, even more than me. I learned a lot from him.”

There’s been a steady flow of new music from Rejjie the past few years. First, his ‘Rejovich’ mixtape in 2013, which featured the Loyle Carner collaboration ‘1992’ and warped jam ‘Lost In Empathy’. Later came the lazy flow of ‘D.R.U.G.S.’, the creeping, smooth ‘Pink Beetle’ and, most recently on Donald Trump’s inauguration, the smouldering comment on police brutality ‘Crooked Cops’ (sample lyric: “Black and white unite my right / these crooked cops they hate my sight”).

Even before the big labels all raced for his signature, Rejjie was doing just fine, bagging a couple of shows supporting Madonna and having tens of thousands of loyal fans following him on social media. “When people care about somebody they’ll fuck with you, they’ll come to your shows no matter what,” he reasons. “That’s down to, just me being identifiable.”

He’s gone with 300 Entertainment, run by music industry big-wig Lyor Cohen and home to Young Thug, Migos and Fetty Wap. Rejjie’s frank about the reasons.

“Money,” he says matter of factly, “and being able to do want I want to do.“Even having a label from America I thought was cool. I could have signed with a UK label – that would have been expected so I wanted to do some iconic shit. A rapper from where I’m from signing to America? It hasn’t been done. I’m trying to open these doors, set an example to other people.”

That’s a theme that keeps coming up. While in the early days back home in Dublin Rejjie may have been ridiculed for having the aspirations and the nerve to follow-through on them, instead of cutting his detractors off, he’s determined to turn it into something positive.

“I’ve got so many friends that just fucked up,” he says, “that didn’t stick to what they were good at, didn’t find a path or never went down that shit so I’m trying as much as I can to do that.

“Yeah, people laugh at you for a month or two, or a year, but at the end of the day they’ll still show respect to you; that’s what I’m finding out now. I’m showing love to everyone who didn’t show love to me.”

All of which brings us to now. In production for a couple of years, his debut album is complete. It’s called ‘Dear Annie’. “I like old sounding names,” he explains, before adding that Annie is an imaginary friend he speaks to throughout the narrative of the album. It’s produced by US producer Rahki (Kendrick Lamar, Eminem, ScHoolboy Q). His attitude towards it, having spent a long time making it, and the recent intervention of his new US colleagues, means he’s both proud of the LP, but also done with it.

“I think it’s going to be the best thing out of the UK this year… it has to be. If not, I’ll quit,” he tells me, not long after clarifying that he doesn’t necessarily think this album is his “moment”.

“As an artist you have a defining moment – I think that’s going to be my next one. I was still learning so much about the industry and myself. Everyone’s got their ‘College Dropout’ you know, this isn’t going to be my ‘College Dropout’. I think it’s fucking sick, though.”

While Rejjie speaks with focus he’s also thinking about the next step, the new project. Right now, in between playing shows, he’s taking singing lessons and wants to put together a live band in the future. This year, as well as the album, he’s bringing out a clothing line and making a short film based on his life with a Detroit-based friend and filmmaker.

“It’s going to show me aged five, get like actors of me, then I’m going to act in it myself. Telling the story,” he says. “There are no limits as a creative person, no barriers. I’m still learning. My next record I don’t even want to make a hip hop record I just want to make music… The evolution of me as the Rejjie persona is just going to go crazy.”

Already, at 23, plotting his own biographical movie, it’s a long way from sitting in the back of the mini-bus belting out ‘Bohemian Rhapsody’ on the motorway to an away game.