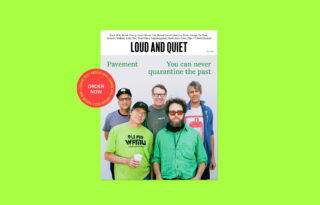

Roughly a week later, I drop in again to find that Pavement appear to be humming like a well-oiled machine. “I hope I’m not jumping the gun here, but think we’re sounding better than we ever have,” Mark Ibold says when I ask how the preparations have been going.

“It’s helped that we’ve had this really great room with very good sound quality,” adds Scott Kannberg, before injecting a note of caution. “I mean, I still wonder if we’re just going to fall apart when we get on a big stage, but I’ll guess to see what happens.”

In many ways, the motive force that propels Pavement comes from the relationship between Malkmus and Kannberg. Childhood friends, the pair of them started what would then go on to become Pavement when they both lived in Stockton, California. In the years that followed, Kannberg’s more grounded everyman persona and straight-up pop sensibilities anchored the more conceptual, high-minded effects of his bandmates. In the band’s later, messier days, Kannberg still had the most skin in the game, was the last to let go and the emotional wreckage still lingers.

“Whenever I heard Pavement songs, I just didn’t enjoy them. It all just seemed so far away to me,” he confesses when we talk about his experiences reconnecting with the material. “It wasn’t until about six months ago that I realised that I would have to actually sit down and relearn all the chords and stuff. I went on YouTube and started watching someone play a Pavement song and just started playing along with them, slowly getting back into the chord structures, and even singing along like Steve used to. Then, suddenly, I was like, ‘Man, these songs are great.’ It’s kind of embarrassing to think it took some guy on YouTube to make me realise how great our songs are.”

In the decade since the 2009 reunion, the whole world seems to have rediscovered and reclassified Pavement. But while the renewed interest definitely has its rewards, with the band finally getting some of the love and attention they deserve, it’s also creating a distorted image of their back catalogue. The weird second life of ‘Harness Your Hopes’ is a case in point. A B-side recorded during the sessions for 1997’s Brighten The Corners that wasn’t released until 1999 when it snuck onto the CD-only Spit On A Stranger EP, it was a track known only to the geekiest, most dedicated collectors. But by some quirk of the algorithm, it’s become the band’s most popular song on Spotify and has gone on to spawn something of a dance craze on TikTok. It’s leaving the band more than a little bemused, with Malkmus writing the whole thing off to Stereogum, saying that the sudden rise in likes was because the track was “on a playlist or something… you know, one of those ‘Monday Moods’ or whatever the fuck they do.”

Kannberg ushers a groan at the mere mention of the song or Spotify. For him, music streaming and social media appear to be necessary evils at best, and should be better kept at arm’s length. “I know that their reach is vast, and things like this have helped get Pavement out there to a bunch of new fans, but I still can’t help but think, ‘Man, we’re just giving this stuff away for free.’ It feels like it cheapens it a bit, you know?”

Still, that hasn’t stopped the band from jumping on the craze. As part of the recent reissue of Terror Twilight, Pavement revisited ‘Harness Your Hopes’ by releasing a new video on YouTube, and the song, along with the Spit on a Stranger EP was finally issued on vinyl back in April. It’s a turn of events that still leaves Mark Ibold more than a bit confused.

“I’m still a bit surprised by our whole response to this,” he says with a roll of his eyes. “First, we go and make a video because some fucking algorithm tells us to, and now we’re practising playing it live. That just doesn’t sound like Pavement to me.”

“I know, man,” sighs Kannberg, understanding his bandmate’s frustration. “But what can you do?”

I guess that’s one of the problems of having a legacy: the bigger it gets, the less control you have over it. As the years go by and the band’s cult status grows ever bigger, their place in popular culture belongs less and less with the creators and more and more with the fans. To me, Pavement felt kind of like a group of kids in the year above, and their music was a roadmap that would help you to figure out the world and your place within it. But as that recedes into the mists of the past, the band’s output also begins to lose the specificity of its meaning, becoming just another star in a galaxy of alternative rock.

“I find it really weird that people equate our band with the ’90s,” says Ibold as we discuss how the perceptions of Pavement have evolved over time. “I was there, and there was a lot of stuff that came out that made me think, ‘Fuck that shit, we shouldn’t have anything to do with that stuff,’ but lo-and-behold, as the years go by, people have attached our band with things that we actively tried to get away from. I guess time and distance skews everything eventually, and things make sense when it was so long ago.”

“I don’t think we come up that much at all,” Kannberg says with a smile. “I mean, people show me new bands and go, ‘Don’t you think this band or that band sound like Pavement?’ but I can never hear us in anything. Yeah, maybe we sound new to these kids, but the only kid I know is mine, and she only really listens to k-pop.”