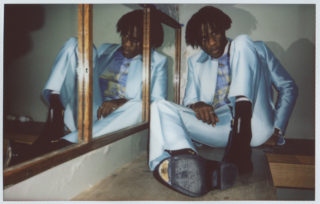

Obongjayar – race, trauma and spirituality in modern Britain

Steven Umoh – in his own words

Steven Umoh – in his own words

If Steven Umoh’s voice sounds unusually knowing, prematurely wise – Thames inflections bleeding into his native Nigerian accent, anchored between rapping and singing – then that’s because he’s lived a lot of life in his 27 years. Born in Calabar, a port city in the south of Nigeria, he moved to London aged 17, then Norwich aged 19, and it was in Norwich that he would become Obongjayar, finding his creative feet. Now, without having released a full album, Umoh’s stock amongst his peers couldn’t be higher. As well as working with people like Giggs, Sampha and Ibeyi, he collaborated with Kamasi Washington on XL boss Richard Russell’s debut solo record, on the track ‘She Said’.

Speaking about the impact of Obongjayar’s work on his own, King Krule explained, “if I wanted to encapsulate something, he has done it for me. When I see his stuff, I’m like, damn that’s fucking amazing.” Obongjayar’s music is hard to define, pitched at a kind of electronic Afrobeat minimalism. Across three EPs – Home, Basse and now Which Way is Forward – Obongjayar has taken ideas from downtempo hip-hop, new soul, electronica, even ambient. All gates open. Where last year’s Bassey was focused on the women in his life and how he related to them, Which Way is Forward deals with his most serious subject matters so far: the personal, the political, the spiritual. The EP is, he explains, “a mirror that allows you to look inward, to understand trauma, to heal.”

I was always into music but never had the opportunity to grow up around it or even actively go out and buy it. I was just listening to stuff that was around. I wasn’t actively listening to music; it was very passive for me when I was growing up. I wasn’t super into anything; it was just stuff that my uncle would play in the car or stuff that I’d hear on the radio or whatnot. It was just like American hip-hop, predominantly that and a little bit of Afrobeat. Then I bought that bootleg Fela Kuti CD from the local music shop, and that was when I thought I was actively trying to get into listening to music. But that just came and went. I was 13, 14 at the time and it was just cool. It didn’t really have any impact on me at the time – I just thought it was cool. I knew I wanted to make music but at that point I wasn’t really trying, or thinking about it in that sense, I just wanted to be exposed to something that was relatable to where I was from.

My mum moved to London, and moving to be with my mum and getting an education for myself was why we left Nigeria. I moved to Norwich just because I wanted to be independent of my mum; I wanted to go somewhere else. I felt that the lifestyle I was trying to live in London… it wasn’t who I was and I wanted to get away from it and start again. Didn’t want to go to university in London because that thing would have continued and I wanted a fresh start. I went to the art school in Norwich to study graphic design and that’s where I met my closest friends, who opened my eyes to a lot of things musically and culture-wise. I dabbled in recording when I was in Nigeria but when I moved to the UK that meant I had more access – the internet was quick, I had access to things like YouTube and SoundCloud. I was intrigued and interested by what was going on. But Norwich was where I really found what I was trying to do musically, what I was trying to get to. I’ve seen both sides of music – I’m part of the generation that bought stuff on iTunes, but then I remember a Bon Iver album coming out on Spotify a week before it was released properly and that was a massive thing. I remember the point when it became as predominant as it is now.

I thought the idea of people who wake up every morning and go for a run was interesting – I put that against the idea of waking up and just going to work, or just getting it, you know what I mean? That’s part of my ritual: I wake up every morning and write or do something that relates to what I’m doing to better myself. That was the idea behind it – not necessarily physically getting up every morning; it’s more of a metaphorical sense, like just trying to survive the day and prep yourself for the next day. That could be writing lyrics or writing a song or trying to make sense of the day before, it’s a good exercise to do and it sharpens your mind, keeps you on point, you don’t miss anything.

I believe in humans and people. When I say spirituality, I don’t mean a God, I mean I believe in people and that we’re in control of our own futures. I’m talking about human beings and being in control of your life. No one’s going to do it for you – coming out from the sky and picking you up – you’ve got to do it yourself, or the people around you. I have a perspective on life and a strong idea of what I’m doing and who I am, but there’s still room for growth, as with everyone. You never really know who you are until the day you die. ‘Still Sun’ is a track about not allowing yourself to be down, or not beating yourself up when you’re down, it’s a cycle isn’t it? You’re down, you’re up, there’s a whole cycle of emotions you go through as a human being. If you’re down, it’s not the end. That’s not the final form and you can get yourself out of that rut. Don’t go and do something that’s going to fuck your whole life up, just keep going man.

An album is a huge deal and you need to figure out what you’re doing before that happens. The next thing I’m going to do will be an album, I just felt I wasn’t ready for an album up until the most recent EP. I wanted to understand what I was doing a little bit more.

I now can’t wait to get to the studio. It’s something new every day – new ideas, new sounds, you never get bored. And it’s also repetition isn’t it – you’re in the studio with people who’ve been doing things a while, you pick things up, you do it in your own solo format and make it yours essentially. That’s pretty much what I’ve done. The reason my stuff sounds the way it does is because I’m being myself and doing things I enjoy rather than following a formula or trying to do something someone else has done – that’s why I think the music sounds the way it does. I take what I need technically, but me and the producer, Barney Lister, we just try and do our own thing rather than following anything. You just get used to that and it just gets better and continues to get better.

It doesn’t matter where I’m from, how much money I’ve got, what I do in society, doesn’t matter who you are. It doesn’t care who you are, it doesn’t know who you are, but it knows you’re Black or Asian. These are stereotypes that have been put on people of colour for the longest time and is how society is run. The EP is trying to change those stereotypes; I’m trying to get people of colour to understand that we can flip the stereotypes if we fight for it.

With those things I’m talking about my experience as a black man in Britain, a Nigerian man in Britain, the things I face when I go through security at the airport and the things I’ve gone through personally. The idea of racism is glossed over now because it’s Britain and it’s so covert, and not as overt as it is in other places – we gloss over it but these things are very prevalent in our society. People like myself have been through a lot worse and a lot of different things that go in that way, so ‘Soldier Ant’ is talking about my experience of being black and Nigerian in Britain, and understand that because of my blackness, it’s a given that I will experience these things.

Photos by: Duncan Loudon