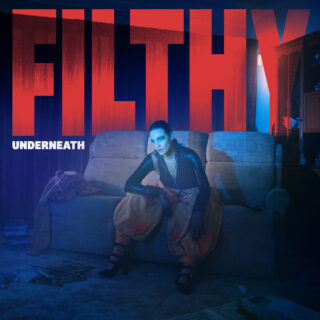

JW: A lot has happened between 2020’s Kitchen Sink and now; more than would be fair or really appropriate for me to attempt to paraphrase on your behalf. How best would you fill newer listeners in on the context of your life over the last few years?

NS: I think I’m aware that now – because of the work I was forced to have to do on myself – that I’ve probably always had underlying mental health issues, but I’ve been able to mask a lot of them enough to get by. But in 2018, my mother was diagnosed with stage four lung cancer, which was essentially a death sentence. She was my best mate, and so I dropped everything; I left London and I moved home to be with her straight away. She lived two full good years, and it was a real privilege to be able to spend that time with her. She died a month after Kitchen Sink was released, and it was lovely that she was able to see that happen. But once she passed away, I didn’t have the tools available to cope. I was heavily self-medicating with substances, and with Covid the normal avenues of grief were not available to so many thousands of us. We weren’t allowed a proper funeral, I wasn’t able to work and have the comfort of touring my album and being with my band on the road. As I was isolated more and more, I got more and more unwell.

The substance abuse got worse and worse until my mental health was at enough of a low in 2022 that I decided to take my own life. It’s tough to talk about. But I’d planned it, and I’d written a letter, then at the last minute, I also did a clumsy tweet. I make jokes about it now, that I didn’t even spell it correctly. But people who knew where I lived saw it, an ambulance and police turned up to my door, and at that moment, it was really a relief of like, “I can stop pretending [I’m okay] now.”

My manager insisted on me going to rehab. I thought I would go for a week or two at most, but I stayed two months, I worked and I realised how poorly I was and I got better. And now I’m a better daughter, a better sister, all the rest of it. It’s constant work. Pain in life, unfortunately, is inevitable. But I feel far better equipped now to cope with those things in a much healthier way than I would then.

JW: I’m incredibly glad to hear it. But as you say, it’s also important to recognise that rehabilitation and recovery isn’t a one-time fix – it takes real work and commitment to find ways to stay well.

NS: Oh yes. Sometimes that work is enjoyable, making sure you go for a walk that day, making sure that you connect with people and don’t isolate. These are beautiful things. But I’m just far more aware now of how fragile the human mind can be. There are certain things in the industry that I know I will need to keep me well, and certain things that I know I can’t have around me. But you’re right; I’m still a work in progress, 100%.

JW: Do you think your awareness of those boundaries has changed the scale of what you want to achieve, careerwise?

NS: I mean, I never, ever wanted to be very famous. I’m quite comfortable with the level I’m at, kind of, you know, mediocre C-list [laughs]. But now, anything that makes me feel uncomfortable or kind of lowers my self-esteem – if I’m offered a certain spot at a festival and I believe I should be higher billed or paid better, for instance – I would say no to. Unfortunately, [artists] don’t always have that luxury, because of finances or whatever, but I think learning the power of no is a very important thing.

JW: You’ve spoken in the past about being somebody who is constantly writing. When did you realise that you were able to put some of these experiences to page in a way that might become a record?

NS: There are songs on this album that are incredibly graphic if you know what they’re about. ‘French Exit’ – I wrote that for myself when I was in rehab as a form of therapy and never intended it to be on the album, but there it is. I do worry about being seen as a ‘role model’; I don’t want to be a spokesperson on the subject of suicide. I’m not a medically trained professional – I’m just an artist who documents things, giving my version of events.

That said, I also really want to dispel the myth of the great tortured artist. I was so high and so unwell at the time of Kitchen Sink that there’s a lot of it I cannot remember writing. And that scared me, because it was my favourite album, and I thought well, I’ll never be able to write like that again. But I want to say to anybody; if you can write a good song drunk, you can write a brilliant song sober. I think people could look at me and go, oh, she needs this pain, because I wrote an album about the refugee crisis, my first album was about two of my close friends who took their own lives, and ironically, it’s then me ten years later trying the same thing. But then I wrote my new song ‘Twenty Things’ in the best place I’ve ever been, sober, out of rehab, with real mental clarity. And you know what, I’ll say it; if I don’t get an Ivor Novello nomination for that, I’ll be deeply upset.