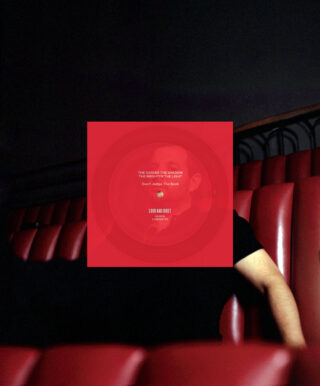

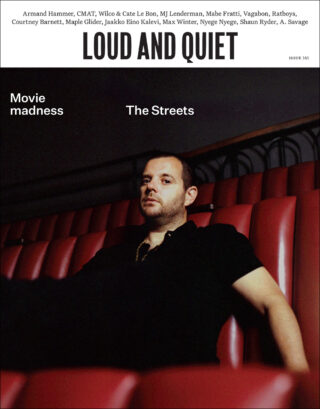

The next time I see Skinner is at our photo shoot, at the Everyman cinema in Muswell Hill. The chain will host a national screening tour of The Darker The Shadow The Brighter The Light in two weeks’ time. We’re now five days away from his deadline. “I’m quite stressed,” he says when I ask him how he’s doing, but once again it doesn’t appear to have affected his mood, as he proceeds to school our photographer in his own gear, clocking the lights he’s using and discussing the development of photographic film, keen to pick up more knowledge from someone who might be able to teach him something. When he nerds out about the fixtures on the light stands, comparing them to the cheaper ones he used on the film so he could jump on and off train with them, his wife Claire, who’s come with him, suggests that he’d be just as happy living life as a photographer’s assistant. He fully agrees.

For now, he’s been combatting stress by becoming obsessed with cruises, and in particular a cruising review YouTube channel called ‘Cruising with Ben and David’, which he instantly sells me on. He says he can’t quite imagine what he’s going to do once the film is finished, so he’d been thinking he might go on a cruise, and he’s been researching the subject exhaustively.

A couple of days later he sent me the opening 25 minutes of the movie, which has already been described as a tripped-out noir murder mystery. A big influence has been the novels of Raymond Chandler, where bourbon-drinking private eye Philip Marlowe cracks cases the cops are too clean for, by straight-talking LA lowlifes and their businessmen bosses, operating just inside the law and getting involved with women who he suspects might get him killed. You know the type of story even if you haven’t read The Big Sleep or watched D.O.A. (another influence) – they typically start with a voiceover that goes something like: “I knew she was trouble the moment she stepped in from the rain.”

The Darker The Shadow The Brighter The Light isn’t set in 1940s Los Angeles, though; it takes place in modern day Britain, in the clubbing world that Skinner has gotten to know very well since The Streets originally ended. But I can instantly see how Chandler and classic noir movies have left their mark; particularly in the dialogue, which sings like the words of Philip Marlowe; how fans of the genre (myself included) wish we all spoke now – cooler, more lyrical and with absolute purpose. “I don’t usually like compliments, but that’s clinging to the things I tell myself,” says Skinner’s lead character shortly after meeting his femme fatale. “It poured itself really, I just held on to keep up appearances,” he says when she thanks him for the whiskey he just poured, itself a trait of the boozy, smoky genre.

I can see what Skinner means about the music narrating the film, and how it comments on the action rather than describes it like A Grand Don’t Come For Free did. It makes those moments feel like abstract music videos, while the straight dialogue in between has the offbeat strangeness of an art house movie that borders on the surreal – at different points in just 25 minutes I get The Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour, Mark Jenkin’s 2019 overdubbed masterpiece Bait and, on one occasion in Skinner’s delivery, Wayne’s World. Which can only be a good thing.

“I never enjoy anything I’ve made,” Skinner told me when we were in the pub. “What I’ve learned is to trust myself. All of the time, I’m working to my tastes. I’m tailor-making stuff to my own taste, so I’ve learned over the years that it’s always to my taste, exactly, if I spend enough time on it.

“I think when I was younger I was aiming for this objective thing. And it’s really not that. It’s completely subjective. You’re just relying on there being enough people out there who have the same taste as you, who appreciate the work you put into making something to your taste. Actually, the worst thing you can do is stop doing it to your taste and stop being so selfish.”

When I asked him how he thinks it’s going to feel releasing a film that he’s spent so long working on, his response was: “I think it’s probably quite shit. But I’m just so looking forward to not having this feeling. Because this feeling has been years and years and years. And it’s a mental health thing. It’s like I’ve got this condition and it’s the film. And no amount of therapy can help me, until I finish the film. Sadly. So all I can think about is that diagnosable disorder being cured by putting it out. Thankfully people seem to like the music. Or they don’t hate the music. I mean, it would be nice if it doesn’t sink and die after two weeks, because I’ve had that happen, where you work hard on stuff and then it just sinks. But that’s the dominant feeling of a creative really.”

“You don’t really think it’s shit though, do you?” I asked.

“No, the film is exactly – and I’m not joking – it’s exactly the way I want it. Exactly. And I think what I’m probably trying to say is that I really know that. Most albums, I think they’re going to take a year and they take two, and this has been ten years, and it’s a completely different thing.

“I think one of the gifts of this is that it’s been so hard that I’m genuinely going to be over the moon when it’s done. And I don’t think anyone will be able to take that away from me. But you can’t not want people to like stuff – that’s ridiculous. But it is what it is. And also, there isn’t any pressure really. If we’d taken 3 million quid, I think we would have been in a different position and doing a lot of interviews with film people.”

From what I know of Mike Skinner, I can’t imagine him ever working like that, with a committee looking over his shoulder and asking where their money’s been spent. He admits he can’t imagine that either.

I’ve also always had a vision of him as a romantic optimist beneath the branded lighters and Stella-lobbing crowds. It’s the way his albums end, in particular: ‘Stay Positive’, the happy version of ‘Empty Cans’ coming after the unhappy, the gospel spirituality of ‘The Escapist’. Even his new album closes with a track called ‘Good Old Daze’. Skinner’s not so sure on this one. “I don’t know the answer to that,” he says, “but I remember when we did The Hardest Way To Make An Easy Living everyone was saying that it was heavy and that it needed to be nicer. I think it would have been even more depressing had I done that alone.

“But I’ve never really thought about it. Am I an optimist? I just take things incredibly slowly. I’m really impatient but I take ages to do something. Maybe what you’re getting though – it’s not me, it’s the fact that I do endings. Because I think stories have endings, but albums don’t.”

I ask if that’s also why he ended The Streets in 2011 – because he wanted it to have a constructed ending?

“No,” he says. “It was because I’d been doing the same thing and I ran out of ideas. It was obvious really. I wanted to make a film, and I didn’t write any lyrics for six or seven years. And it was mad, I had no desire to write lyrics – I was DJing and producing stuff and directing. I had absolutely no desire, and then it was really organic. Something in my mind made me really miss it. I hadn’t stopped for ten years, and I think my brain was just exhausted. But it was quite weird. Because I write songs, I perform them, I DJ, I direct. Every different one scratches a different itch, and there’s a certain thing with words that nothing else really does. Words are really cool, and you can’t scratch that itch by DJing.”

Get an exclusive Streets track on flexi disc when you subscribe to Loud And Quiet this month

Get an exclusive Streets track on flexi disc when you subscribe to Loud And Quiet this month

Mike Skinner: “The actual album that’s coming out – I’ve had that for a while, years really, and the film and music kind of wrap around each other. I also knew I needed other music to score it out and to fill in some of the gaps once the filming started, so I made some more music and we put it out there to plant some seeds, really. I called that ‘extra’ album “The Streets” by “The Darker The Shadow The Brighter The Light” [released digitally in 2021] – the polar opposite of the album that’s coming out with the film, but it’s all part of the same thing, really.

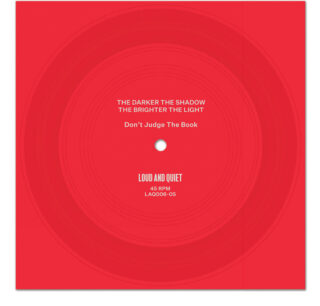

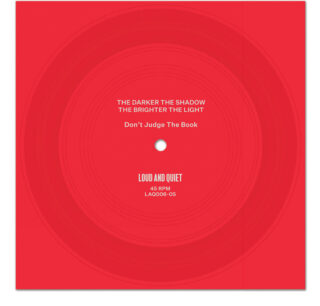

“The song ‘Don’t Judge The Book’ – it’s quite literal, honestly: sometimes a film can let down the original text, sometimes it’s the other way round. My film – the music, the film, it’s all so interwoven, but I would hope either can be enjoyed separately. It’s been a lifelong ambition and project, and it’s been over a decade-long obsession. Everything has geared towards this so everything I made – even the mixtape we did – was testing some film ideas and buying time when the pandemic came; everything has led up to this moment. A lot of the songs from that album (The Streets by TDTSTBTL) have made it into the film – and I hope that makes it all make more sense now.”

Subscribe to receive an exclusive flexi disc from us with each issue of L&Q. Sign up at loudandquiet.com/subscribe

Get an exclusive Streets track on flexi disc when you subscribe to Loud And Quiet this month

Get an exclusive Streets track on flexi disc when you subscribe to Loud And Quiet this month