Inside her dockside shipping container studio, Mica Levi remains avant-pop’s most lawless star

Ship Shape

Ship Shape

Over the past three or fours years, Mica Levi has been hard at work, and if you have even the slightest interest in London’s young music scene, then you’ll at least have heard of her. Whether it’s with her band Micachu and the Shapes, her involvement in the Kwesachu mixtapes (with kindred Free Pop artist Kwes), or even her efforts on works by the likes of Dels, The Invisible, Speech Debelle and so many more, you can’t exactly say she hasn’t been putting herself out there. Yet Mica Levi, born and bred on the outskirts of London, is still relatively unknown.

In 2009, her debut album, ‘Jewellery’, dropped to accolades from the press, but she’s still topping tiny venues like The Queen’s Head in Islington, London, and Hoxton Bar & Kitchen. The Southbank Centre has recruited her as artist in residence, but despite various turns in the grander Queen Elizabeth Hall, she’s not selling the place out. That’s not to say that she isn’t talented – that’s the reason why everyone wants to work with her. It’s perhaps because of the niche market that Mica targets with her erratic brand of grimey alt.pop. Unconventional ‘instruments’ – such as hoovers, broken bottles, discarded CD racks and playing cards – jar against one another in a way that should be discordant (and certainly is to some), but not to the cult following she’s built up.

A Pitchfork reviewer said of her debut LP, “on first listen, it’s a maddening noise; by the fourth, it’s as catchy as a jingle.” It was ‘Jewellery’’s most accurate critique. Micachu and the Shapes are definite growers, but once they’ve planted the seed, those avant-pop clusters become increasingly more appealing, until you realise that what you’ve been presented with is essentially the sound of household objects backed by a paired-down, guitar-drums-keys band on repeat for the last hour.

Of course, no matter the genre, pitch, speed, style and whatever else Mica can alter and bend, music is something that has always come naturally to her. Being born into a family of musicians all of 25 years ago allowed the precocious singer-songwriter to begin honing her talents long before she can even remember her interest in music blossoming. “It’s hard to talk about it because I’ve never really done anything else,” she muses. “That’s like somebody asking you, ‘so when was it that you started wearing jeans?’ Well, I feel like I’ve always worn them and lots of other people I know wear them. It’s always been there. I just liked listening to music and I’ve gone through phases of being interested in different kinds, trying different things out. Sometimes quite publicly, I guess.”

After a thorough stint at the Purcell School of Music, followed by a Guildhall scholarship – where she was commissioned to compose a piece for the London Philharmonic Orchestra – Mica cut her teeth in the UK grime/garage scene. Although it may not be obvious in her Micachu and the Shapes releases, hip hop is a major influence for her. The fact that the first Micachu release, ‘Filthy Friends’, was a mixtape is a big hint, but enlisting the help of a now thoroughly established crew of producers and MC’s such as Ghostpoet, Man Like Me, Kwes and Toddla T didn’t exactly dampen her urban credentials. This has led her to more collaborations with Kwes on further mixtapes with huge acts in the electro sphere, including Hot Chip, Metronomy and The xx. The summer of 2009 saw her slow-rhyming on Mercury Prize-winner Speech Debelle’s track ‘Better Days’ and last year she produced a couple of songs on Dels’ debut album, ‘GOB’. Not to mention writing ‘Chopped and Screwed’ while on tour – a digital meets analogue performance with the London Sinfonietta.

Mica’s not exactly a girl you can hold down. Before we meet up, she was in Brazil checking out the NEOJIBA orchestra, a government funded orchestral training programme. She’s forever thinking about music and how to incorporate a seemingly endless selection of elements. “I don’t think I’m ever happy with the sound,” she sighs before wrinkling her nose and countering her comment. “I don’t mean it like that. I’m always excited by different things and I don’t think that’s necessarily because I haven’t heard it before, it just has to come into fruition at the right time. It’s peaks and troughs – things come round and back round all the time, whether it be a speed thing or a style or an attitude thing. With music in England things get recycled a lot and I always try to keep my ears open. If I’m excited about something, then it feeds through, but it’s best not to think about it too hard.”

As she says this, she’s slouched on the sofa in what the estate agents would call an ‘intimate’ old shipping container that doubles up as her recording studio in Trinity Buoy Wharf. Out here in the docks of east London is a hotbed of emerging talent in both music and art. It’s also home to a stellar view of the huge, industrial Millennium Dome and London’s only lighthouse.

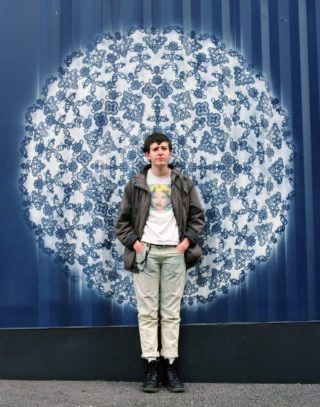

Spinning on the decks is a Prefuse 73 record, while on the wall behind Mica is the psychedelic backdrop to an image of her and Kwes that has become synonymous with their second Kwesachu mixtape. Next to her is Kwes’s ‘No Need to Run’ EP, along with a promo of her new album, ‘Never’. That is, of course, what we’re really here to discuss, but it’s so much easier to understand Mica’s use of grating synth lines and warped fairground vibes that blanket her new album if you follow her process from the start, and apparently it was a completely different ballpark for her back then when it came to approaching music.

“I can’t even remember, ‘Jewellery’ was so long ago,” she says. “I’d done half on my laptop in my bedroom and then I went to Matthew’s [Herbert] studio and we thickened it up. Mate, it was so lo-fi. Then the band started halfway through. It’s quite a weird record in that way. It’s half a live band that had been together for a month and half a laptop bedroom thing. This one [‘Never’] is different, though, it was collaborative. We wrote and recorded as a band, as opposed to last time when I recorded with the band, but then went away to work on it with Matthew.”

This time around Mica didn’t work with the experimental electronic pioneer Herbert, or any producer for that matter. The band did everything themselves, which Mica professes was hard work. “I’d like to just not have to think too hard,” she admits. “I sound lazy, but I don’t mean I don’t want to do anything. What I mean is that I want to concentrate on my bit, which is singing and playing guitar. You’ve got to know what your strengths are and when to use someone else’s strengths for the right thing.”

By creating ‘Never’ on their own, it only took the trio – completed by Raisa Khan and Marc Pell – a month, whereas ‘Jewellery’ was done in two halves over the course of a year. But there’s still been a considerable three years between the two. “I’ve been really busy, though, that’s why,” assures Mica, “with different kinds of projects and making beats and other bands. We toured ‘Jewellery’ for ages and I didn’t feel like there was a mad rush to do it. There’s so much music happening all the time, you’ve just gotta do it at your own pace.”

In the break that the group had, Raisa was performing in Dels’ band, as well as doing her solo project, Raisa K; Marc was playing with We Have Band; Mica was undertaking every project under the sun, including boxing, and in that time there hasn’t been a huge leap between the sound of both records, but you can tell that, despite apparently listening to more “straight up rock ’n’ roll”, there is an ounce more experimentation. For instance, could you have guessed that a telephone and a transsexual walking in heels played parts in the making of ‘Never’? Or that Mica has been channelling The Only Way is Essex?

“In my mind it’s quite traditional,” mutters Mica, nonplussed. “I needed the sound of somebody walking up the stairs and that was the best I could do,” she explains about the sampling of her transsexual friend. “‘Top Floor’ starts with footsteps – hopefully it sounds like somebody walking up to the top floor – but it’s actually somebody walking back and forth in heels. I wasn’t here in the studio, I was in my room and I didn’t have half a coconut or concrete stairs, so that’s what I used.”

At the thought of ‘TOWIE’, Mica blushes slightly. On ‘Glamour’, there’s a snippet of an obnoxious conversation that was originally a sample from the reality TV show. “We weren’t allowed to use it, so I got my friend, who went to school in Essex, to say it. I don’t know why it’s in there, it made sense at the time. It’s me having a conversation with a glamour model. Well, not necessarily me, but somebody, and being quite creepy about it because they’ve seen them in a magazine. I thought it’d be quite fun to have a conversation in there because it’s all meant to be quite filmic.”

When Mica says filmic, she doesn’t necessarily mean in a conceptual way. She’s referring to the aesthetic and feel of the LP, so she grabs the promo to explain the cover, which looks like a purposefully poor quality image of old school embossed wallpaper with simple graphics overlaid. “It’s supposed to be like a ’70s film poster,” she points at it, “that nostalgic thing. That’s why there’re a few sound effects in there, because it’s supposed to be like a soundtrack.”

So, although the album does follow a loose narrative, in the way a film score would, it doesn’t tell a story on its own. However, some tracks do fit together. “It’s just that camp idea of adding extra drama and effects in there. It’s meant to be fun,” Mica adds. “I guess it is a bit conceptual in terms of the ordering. So, ‘Top Floor’ is about jumping off a building. That might not be obvious, but it’s about going up to the top floor and thinking about jumping off – then the next track is ‘Fall’.”

It’s with ‘Fall’ that the album takes a dip into eerie ballad territory. Thrumming, jazzy bass lines back Mica’s quite even, straight-ahead drawl, both of which are broken up by wayward drum rolls and offkilter beats. After a short silence, the track starts up again with what sounds like a movie reel snapping back into action after a rest, with a crackling, string assisted soundtrack to take the listener into the haunting ‘Nothing’. On this, both Mica and Marc sing about some psychotic character who “cracked a grin” as the “painfully thin” protagonist retched to a demented organ that stumbles all over the place. If this was soundtracking a film, we’re quite sure it’d be a psychotic thriller.

Inexplicably following after ‘Nothing’ and to close the album is ‘Nowhere’, which is an explosion of brash, energetic drums, chants and frantic riffery. Mica thinks on this for a while, furrowing her brow. “I don’t know,” she finally pipes up. “We spent a while ordering the album… no we didn’t actually spend a while on it, we just did it. But yeah, it does slow down towards the end and then is mad again for one song. I hadn’t really thought about it. The reason is, there’s no rhyme or reason to it.” And with that she reveals a gappy grin. “I guess I’d like to have an answer but I don’t.”

With a lot of things Mica does, there’s no real method or planning to it. Even when she takes on more work than she can manage, she still starts on something else or at least is aching to. “I’m always thinking about music, so I’m always doing things I shouldn’t be doing. If I’ve got a deadline for something, I won’t really want to do it, I’ll start a new project.” She sighs at her inability to devote her focus to one thing at a time. “Sometimes it works out well,” she defends, “sometimes I get in trouble. But it’s freeing – it’s difficult when you’re being told to do something. I’m trying to come up with a bit of a system, but you don’t want to lock yourself down.”

When it comes to actually writing the backbone of a song, there is one routine she favours. “I like singing first,” she says. “Singing some words I’ve written, making up a melody and then harmonising that. It depends, because I’ve been writing a lot more on guitar recently, but if I’m doing electronic music it’s best to start with singing.

“If you think about the words in your mind, then you might use intonation – the way that you say it might be more natural. If you’re trying to fit words into something you’ve sung, it can work, but I think it’s better if you say a sentence the way you’d say it in real life. Then if you put an accent on or lengthen a certain word, it might become funny or more interesting because you wouldn’t normally do it that way. To be honest, I’m still getting to grips with it. I wish I had a way. That’s what I’m aiming to get in the near future – a pattern and a way.”

Not having to stick to too many personal deadlines and an overflowing mount of ideas, means that Micachu and the Shapes end up writing stacks of new material constantly. In recent live shows they’ve already started playing new songs and the second album isn’t even out yet. “I just want to put out another album quite soon,” she says with a knowing smile. “Because we took a break, when we got back together and started playing again it was fun to keep writing stuff. Also, with going on tour, it keeps things moving, keeps the freshness. You have to keep trying things out, otherwise you get stuck if you’re just playing the same stuff over and over again. I hate doing that.

“I guess when we go on tour we’ll probably put some older songs in the set, but at the moment, I don’t think a lot of people know who we are, so we can play whatever we want.”

It’s at this point that her friend Taza rocks up to record and Mica tells me that it’s been “like Piccadilly Circus” all day. Her mum and sister have already stopped by for doughnuts and tea, her neighbour Pete has been round with her repaired hard drive and shortly before we sat down with her, she was doing a photo shoot. Obviously her mum and sister have to love her unconditionally, but it says a lot about Mica as a person that so many people – both big and small name artists – want to help her out and collaborate with her. But when I ask how she manages to build up such a great rapport with so many people, we’re met with a silent stare of genuine puzzlement.

“Er…I don’t know,” she blinks. “The London music scene is quite small and when I did the first mixtape in 2008 or 2009 everyone was starting out and it was just a way to mix everything together. I think it’s because I do producing as well. If I was just in a band I probably wouldn’t meet so many people, but producers work with so many different acts. It doesn’t always work out, but I guess doing mixtapes is a good way of showing little sketches or ideas without committing to an album or an EP project. And it shows relationships that maybe loads of other people have but aren’t in the open, because the project never pans out to be a proper thing. I don’t know, I think lots of people know each other but sometimes they don’t write together. But I guess communicating with people and having remixes – that builds relationships between people. Like Taz. This is Taz – Taza, she’s a singer.” She gestures towards the girl who’s just walked in and positioned herself towards the ‘back’ of the room.

So out of all these joint ventures, there must be one person who Mica really favours working with – that one collaboration that when they’re together, everything just falls into place. “Oh man,” she pauses, eyes wide, before spluttering “Taza” and erupting with laughter. “It’s not really that simple,” she answers once she regains her composure and Taza buries her grin in an art book. “I couldn’t say. There are different things about each one of the main collaborations I’ve had – the one with Kwes and my band and Matthew – I don’t know, there’s always something to gain from those. That sounds fucking cheesy, doesn’t it? I don’t know, it depends really. It’s a relationship, so sometimes it’s really working, sometimes it’s not as exciting as it was and sometimes it gets more exciting than it ever has been.”

Obviously working with alt-disco juggernauts Hot Chip and Metronomy – not forgetting the likes of Jack Penate and Golden Silvers on top of that – is a pretty big deal in the industry and has probably opened all kinds of doors for future work. “I don’t know, we’ll have to see.” Mica brushes off the enquiry in what we want to believe is a secretive tone but feel is actually just bear honesty. “I could continue working with a lot of people who I already do, no doubt, and hopefully I’ll go and work with some musicians in Brazil. But I guess I should keep it as a surprise. It’s gotta be on the fly, otherwise if I make a plan to work with Nicki Minaj and it doesn’t happen, I’ll feel really disappointed.”

For now, the experimental pop maverick and her ‘Shapes’ are incredibly busy, so they wouldn’t exactly have time for Ms Minaj, even if the iconic, RnB star requested them personally. Firstly, they’ve got to conquer the States: “We’re going to put out this album and go to New York to tell people about it. Then make loads of videos because that’s a good way to change things up a bit. So yeah, just busy, it’s good to be busy, although I’d like to not be busy, actually.”

After New York, the trio are aiming to head out on a tour of the UK and Europe and who knows – maybe 2012 will be the year that the group finally go stratospheric, should mainstream pop start yearning for an avant garde twist on the genre. But when it comes to Mica’s own future, there’s a clear classical path. “My ambition was always to be a composer of classical music,” she states adamantly. “I was still in college when I started doing this side thing, but then that took over. I’m hoping to write a piece this year actually. That’s my long term plan – what I wanna do when I’m older. When I grow up.”