Maxine Peake – A long talk with the British actor about becoming Nico

"Men are seen as exotic and intellectual and exciting if they’re unlikeable, there’s something mysterious about them. But with a woman it’s quite different"

"Men are seen as exotic and intellectual and exciting if they’re unlikeable, there’s something mysterious about them. But with a woman it’s quite different"

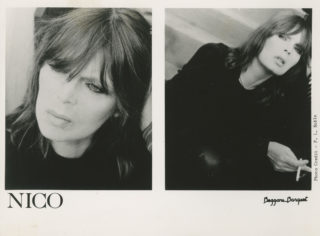

The seventh edition of the biennial Manchester International Festival begins on 4 July and runs for eighteen days, taking in newly commissioned work from artists ranging from Yoko Ono to David Lynch, Philip Glass to Skepta. One of the most eye-catching new pieces is ‘The Nico Project’; a theatrical re-telling of Nico’s 1968 masterpiece The Marble Index, written by playwright EV Crowe, directed by former Royal Exchange artistic director Sarah Frankcom and starring Maxine Peake; just three members of an all-female creative team. It marks the latest in a series of collaborations between Peake and the MIF and I took the opportunity to speak to her about the project’s inception and how Nico’s story tells us something about what it means to be a female artist.

The early information I’ve seen about The Nico Project keeps things fairly enigmatic. What can you say about the form that it’s going to take?

Well, one thing it’s not, it’s not a bio at all. This isn’t going to chart the rise and fall of Nico through her career. It’s a group of female collaborators that got together to talk about what it means to be a woman and a female artist. And Nico actually struggled sometimes with her femininity: she felt that like many women it held her back. In one interview she was asked if she had any regrets and she said, “That I wasn’t a man”. She was someone who was idolised for her beauty for the majority of her modelling and acting career and I think it was something that she resented. So we just started to talk about what it means to be a woman and be an artist and the transference between an actor on stage and the character you’re creating. It’s a performance piece, it’s not a play. We’ve got an orchestra, we’ve got Anna Clyne – the composer – she’s British-born but based in New York. She has re-imagined The Marble Index and we have an orchestra of I think between eight and twelve young women from the Royal Northern College of Music who will be playing alongside me. I will have a harmonium – I’m having harmonium lessons and there will be some singing involved. But if people think they’re coming to see a Nico bio, they’ll be disappointed because that’s not it. We’re using Nico as our basis for the creation, but we don’t go too much into her personal life story.

It’s interesting that it’s based around The Marble Index in particular. That was her second album, but it was the first one that she wrote herself, and it was a massive shift for her.

Yeah, and it’s the album she seemed proudest of – it’s what she wanted. I think with Chelsea Girl and others she felt she’d been slightly pushed in one direction and the production wasn’t what she was wanting. This felt closer, from what I can gather, to her expression.

And it was less of the beauty cliché that the first album was, with less of the softly softly vocals.

Well, that’s it. I’ve just been watching Nico Icon again, the documentary, and somebody was saying when she dyed her hair from blonde to dark, someone asked her, “Why have you done that, you look ugly,” and she said, “Good!” I think everyone thinks it must be some blessing to have that kind of beauty but at the same time it can be a double-edged sword, to be so objectified. And you can only imagine what she might have gone through in the modelling and film industry at that time, you know what I mean, with everything that’s come to light today, the more you think about it, the more you think gosh, she must have had some battles on her hands. You wonder whether that had a big influence on her turning her back on all that. And obviously, the bohemian life seemed to have a big pull for her.

It’s telling that that album was pretty much ignored when it came out as well. The world just wasn’t interested in hearing such an expression from somebody like her.

Well, from a woman as well. I know Scott Walker’s stuff became progressively more avant-garde as time went on, but I think I would put those two – they’re different – but there’s something very similar between them. But Scott was lauded and as you say, she was sort of ignored.

How much of you playing Nico is you having to figure out how she speaks, how she moves – are you trying to capture her, or is it more abstract than that?

I think there is an element of catching her and then there’s an element of transition from actor to character and how that works. But yeah, I’ve been studying her and obviously I’ve been a fan for a long time, but even if you’re a fan of somebody, you don’t necessarily look at them as a character study. So there will be some Nico-isms, and I will be trying to portray her on stage or conjure up some of her personality.

You say you’ve been a fan of hers for a long time. Do you remember your first experience of her?

It was through The Velvet Underground, to be honest, through being a fan of theirs. And then hearing Nico and somebody telling me that she did some solo stuff, then I got into her through that. It’s just interesting her relationship with Lou Reed and that band. Again, she was given to them by Warhol wasn’t she – he was like the avant-garde Stock Aitken Waterman! It was that sort of, “We think this is what you need for your image, this is what you will do”.

Pete Waterman will be delighted with that, I’m sure.

Yeah, I’m sure he would. Thank god Andy Warhol is no longer with us! I could be in trouble.

So when did you become aware of this fabled period when Nico was living in Manchester?

I think it was when I read James Young’s book [Songs They Never Play on the Radio]. I’m friends with Carol Morley, the filmmaker, I’ve worked with Carol a few times and we’re good pals. Carol used to clean for her and Anton Corbijn at one point. I mean, I think that’s quite interesting! It was just one of those, I’d sort of always heard that she’d ended up in Manchester and there were always those stories – you’d see Mick Hucknall on his bike and you’d see Nico on her bike. Again, I’m not comparing those two people!

I’m hearing names that I wasn’t expecting to hear in this interview.

Haha, I know. I’ve given you Pete Waterman and Mick Hucknall! I just remember being a teenager and people would say they’d seen her going up and down on her bike. It was probably my late teens and early twenties. You can’t quite compute it; it’s such an extraordinary story. When you look at the early images of her in the late ’50s, early ’60s, modelling pillbox hats and full dresses, to then this complete transformation. I don’t know anybody really who’s been on that complete journey from one end of the spectrum to the other. And then I read James Young’s book and that’s one of my favourite books – especially one of my favourite rock bios – it’s a fantastic piece of writing. And in some ways it’s not really about Nico, it’s about James’ experiences at that time and it’s about Manchester and that romantic view we still have of the late ’70s, but very dank and grey, that sort of bohemian Manchester and lots of drugs.

It probably did remind her a bit of Berlin when she was a kid.

Exactly. Well I think that’s it. And there’s always been that link between Manchester and Berlin and the industrial Germany, when you look at Joy Division and all those kind of bands. In a funny way, the Second World War is the link. I suppose the generation of parents of the people in those bands would have experienced the war and it’s something that just hung over Manchester, and all over the country, nationwide. It was still very much in the atmosphere. And there are a lot of similarities between the Northern industrial towns and those towns in Germany too.

Does the Manchester part of her life play into The Nico Project?

I mean, because it’s not such straightforward storytelling, it’s not like we say, “And then she lived in Manchester.” I think that’s what we wanted to get away from at [Manchester International Festival]. There are a lot – and it’s great – of men of a certain age who have a monopoly on Manchester’s musical history, and they keep the myth alive, so we didn’t want to go down the obvious track with it. And obviously she’s not from Manchester, but she played an important role in Manchester’s musical history, and it played an important part in her development. So we’ve tried to keep it slightly more abstract.

Has it helped being able to speak to people who would have spent time with her?

Yeah, I collaborated with Johnny Marr and he was telling me about going to the Hacienda and she’d just sort of be sat there and he’d sit there and she was pleasant enough but there was something very closed off about her, very intriguing. But obviously they were big Velvets fans thinking. “Wow, that’s Nico!” So yeah, Johnny, Carol as I said, and Adrian Flanagan (The Moonlandingz, International Teachers of Pop), who I’m going off with to record our next album as The Eccentronic Research Council, he used to see her down the pubs in Prestwich. Everyone’s been very forthcoming. I met up with James Young too – he came to speak with us about his experiences with her. It’s that Mark E. Smith thing – a lot of people didn’t seem to particularly like her, but she had this huge influence and impact on them and obviously left a mark. That’s what we’re intrigued with, when women are deemed not to be accessible – what does that mean anyway, I hate that. Men are seen as exotic and intellectual and exciting if they’re unlikeable, there’s something mysterious about them. But with a woman it’s quite different.

As is often the case with artists as complex as Nico, do you worry about the things that perhaps aren’t to be celebrated about her?

Oh yeah, we’re not going, “Well, she was a great person.” If you scratch the surface with most artists, you will find something that’s not likeable. Again, it’s been slightly more highlighted because she’s a woman. Yes, she said some really contentious things and some very hateful things that we’re not making excuses for. But it’s that age-old question isn’t it, what do you do if you look at an artist, do we confine them to history because of that? She’s a complex woman.

I know you’ve worked a lot with the director of The Nico Project, Sarah Frankcom, who just recently stepped down as the Artistic Director at the Royal Exchange, and this is an all-female creative team.

Female director, female artist and writer, female choreographer, composer, sound, lighting design, all female.

And is that by design?

Well it’s sort of just how it happened. We just decided we wanted to work with people that we wanted to work with, and it just turned out in a funny way that it became all female. It wasn’t conscious but it did just feel right at this point. When we started to look at people that we thought might be interested in the project and who would bring what we thought would be needed, we felt that this was the way to go.

The show is running for twelve nights, and then will that be it or will there be life for it beyond MIF?

Well, we’re in discussions. We were talking about bringing it to London at one stage, but it’s always hard trying to find people to invest in projects. Yeah, we’ve got a few people we’re talking to. I suppose it depends how well it goes down. We did want to do it specifically for the festival. It’s like when Sarah and I make pieces for the [Royal Exchange] – we’re making it for Manchester, we haven’t got our eye on London or somewhere else. I mean, it would be lovely if somewhere else went, “We really like it, we’d like to produce it as well,” but it’s never in your game plan. But we’ll see, it’ll be great to go somewhere with it.

It’s not like you’re busy or anything.

Ha, yeah, I would be struggling to fit it in.

Photo: Jon Shard