Lil B has become the talk of hip-hop, wrapping himself in his own web-savvy mythology

Young rap loves hip, old rap definitely doesn't. Chal Ravens investigates who's right out of the lovers and haters, and just how god-like the BasedGod is.

Young rap loves hip, old rap definitely doesn't. Chal Ravens investigates who's right out of the lovers and haters, and just how god-like the BasedGod is.

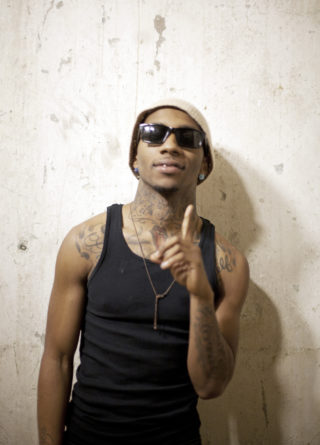

“Ellen DeGeneres! Swag! Ellen DeGeneres! Woo!” Flanked by a brick wall of security muscle, a snake-hipped Californian, little more than 5ft 7”, is whipping the crowd into a froth of flailing arms and pumping fists, blue light glinting off his gold teeth and shades as he announces himself humbly as the ‘BasedGod’. It can only be hip hop’s most divisive figure for a generation: Brandon McCartney, or as you probably know him, Lil B.

“First I park my car, then I fuck your bitch!” he chants in the nasal drawl heard on his most banal and ridiculous tracks, as his fans lurch forward as one to swamp the stage for the chorus of ‘Wonton Soup’, B’s biggest hit (where ‘hit’ means ‘most viewed on YouTube’ – eight million views and counting). Tonight’s set is weighted heavily towards his most notorious meme-spawning material, including ‘Green Card’, ‘I Own Swag’ and newer, um, songs, like ‘Ima Eat Her Ass’ and ‘Please Respect the Bitch’. The big guys on stage get tough with the invaders, tossing them back into the throng and twiddling their earpieces as if the crowd want anything more dangerous than to pogo along with their hero, screeching, “Swag! swag! swag!”

Before wrapping up at 9.30pm (the early slot is necessary for the hour-long meet-and-greet session afterwards), B tries out one of his ‘Based freestyles’, this time a pretty hopeless example of his notoriously hit-and-miss improvisations. He tests a few lines, grinning at a successful rhyme but reverting to the chant of “Young BasedGod” when he fails to tease a couplet from his brain. While half the crowd lose their minds at the front, a significant proportion of attendees are skulking further back, sizing up B as a foreign curiosity rather than a demigod. When he announces the last song, there’s a decisive dash for the exit among the lone gig-goers who’ve heard all they need to hear. The patient devotees, on the other hand, queue up for an hour to get their souvenir snap, to be tweeted immediately in the hope of a retweet from @LilBThePack1 himself (verified; 431,800 followers and rising).

In that moment, the entire Lil B narrative is neatly illustrated. A rapper with a million fans and nearly as many haters, Brandon McCartney’s journey from skate brat to underground superstar has attracted no small amount of controversy and column inches along the way. No longer considered a young buck in the game (he was named in U.S. hip hop magazine XXL’s ‘Freshman Class’ feature last year), B’s influence can now be heard in mainstream rap and chart pop, while critics from blogs and broadsheets ruminate on the meanings of ‘Based’ music.

Many listeners, though, are bewildered by the hype, arguing that he plain can’t rap and has no business calling himself a ‘god’ of hip hop, ‘based’ or otherwise. It’s time to find out more, so we wait patiently backstage while the fans get their starstruck moment. An assortment of over-dressed hangers-on pace around behind the curtains, flashing shiny varsity jackets, wrist-to-wrist tattoos and freshly purchased snapbacks. Lou Pocus, a producer from Bedford who’s made a few beats for B, has brought his crew in and waits to shake hands with his collaborator and pass on some contraband, which is gratefully received. Gatecrashers and groupies line the walls as security guards vainly attempt to weed out imposters.

In the midst of chaos, B’s manager floats calmly, packing up the limited equipment they’ve brought with them. A true San Franciscan, long-haired and impossibly relaxed, he also sorts out the backing tracks during the set – no hype man or DJ on this tour – and shepherds B towards the various interviews, taxis and flights using a paper plate, on the back of which are the phone numbers for XOYO [the venue we’re in] and Addison Lee scrawled in green. By the time we pin the rapper down for our post-show interview, it becomes obvious we’ll be lucky to steal 20 minutes of his time. They’ve got an early morning flight to catch and, by the looks of it, the night is young for B.

In scruffy basketball shorts, yellow knee socks and a pair of tatty Vans, B cuts a modest figure, with the exception of his full grill and chestful of tattoos (the centrepiece reads: Lord, protect me from myself). He greets everyone enthusiastically and seems pleased with the show: “One of my favourites, definitely.” A film crew ask how he prepares before going onstage. Perhaps we were expecting vocal exercises, or liquor and blunts, but this is San Francisco’s Lil B we’re talking about. “Just meditate,” he says, “and get my high right.”

It’s not the orgiastic nihilism you might expect from the guy with “four diamond rings, two big-ass chains”. For every ‘swag’ there’s a ‘based’ – once a term of abuse directed at ‘basehead’ crack addicts, now reclaimed as the linchpin of an entire philosophy of sorts, a brand of positive thinking that betrays his upbringing in the hippy homeland and college town of Berkeley.

Lil B’s first taste of fame came when he was just 16 with The Pack, a teenage crew who scored a hit in 2006 with the skate anthem ‘Vans’, an ode to lace-up shoes over a sparse ‘Drop It Like It’s Hot’-style groove. The Pack dissolved after a disappointing experience with their major label, but B set to work on his own material, assisted by producer Young L and a huge supporting cast of beatmakers. He’s clocked up 30 official releases since 2009, all free to download, with a zero-budget video accompanying virtually every track. “I’m at, like, 1,500 to 2,000 tracks,” he says. He must have to revise sometimes. “I got a lot of stuff to remember, so yeah, I definitely go back and listen to it all.” So nothing gets lost and forgotten in the back catalogue? “Everything’s special, everything’s equally valued. I take pride in quality over quantity, and just kind of doing what’s true, true to myself.”

Quality over quantity, it must be said, is not the apparent modus operandi of the BasedGod, whose promotional strategy has essentially been a war of attrition using YouTube, Twitter and sheer prolificacy as his weapons. Quality control is not so much ignored as gleefully stamped out, with B often recording his bars in a single take for optimum “honesty”, as he describes it, even when that means leaving in the false starts, missed beats and countless ‘Based freestyles’ that taper off into nonsense. Some tracks contain barely any lyrics in the traditional sense – check ‘Bitch I’m Bill Clinton’, where he intones “White House, White House” in lieu of a chorus and chants, “Flag Bill Clinton, car Bill Clinton, house Bill Clinton, girls love Clinton”. Fans of Q-Tip, Chuck D, Eminem or the rest of rap’s big-hitters might find it infuriating, but it’s not hard to imagine a Mark E. Smith fan digging the abstract repetition.

B raps over whatever beats he can find – luckily he now has so many producers sending him material that he’s spoilt for choice for the next few years. Among them is Clams Casino, New Jersey’s Mike Volpe, who got his break providing the music to ‘I’m God’, ‘Motivation’ and ‘Cold War’, and has since broken through with his brilliant ‘Instrumentals Mixtape’ and productions for Harlem’s A$AP crew and Main Attrakionz.

Along with Keyboard Kid 206’s beats, these ‘cloud rap’ instrumentals are some of the tightest productions for his raps so far, standing in contrast to the overblown ‘swag rap’ tracks which take their cue from the Dirty South’s blaring horns, ratatat snares and sagging bass distorted by volume. The tackiness is matched by the sleazy artwork, depicting B nestled among rows of diamonds and rising flames, and videos like the recent one for ‘Bitch Doing 30’, in which a stripper wobbles and gyrates in plastic heels and yellow bikini for the entire length of the song, any hint of sexiness displaced by awkwardness and, eventually, absurd humour.

The hip hop purists hate it, of course. Usually, the most gifted lyricists are venerated by their peers and cultural gatekeepers like label bosses and journalists – look at lauded rappers like DOOM, GZA and Mos Def. The connection between rap and poetry has been made explicit, and rappers who want to be taken seriously need to get their words in order. In contrast, the street element of hip hop – ‘trap rap’, in its latest formulation – is seen as simple-minded and disposable, the unconscious counterpart to the dreaded ‘conscious hip hop’ (a separation that only serves to conceal unspoken judgments on race and class, you could argue).

But listen again to B’s rapping in The Pack. He can flow if he wants to – he just isn’t doing it anymore. He may not be a wordsmith in the dictionary-swallowing style of the Anticon label, but he has a knack for phrases so off the wall that they lodge in your brain, cryptic and unfathomable. In that sense, it’s hard to think of precursors to his style other than, at a stretch, the surreal craziness of Kool Keith or the true original that was Ol’ Dirty Bastard. When B does turn his hand to a more conventional hip hop sound, as on last year’s reflective ‘Illusions of Grandeur’ mixtape, his technical weaknesses are revealed and the mixtape is forgettable in comparison to the records he intends to reference (‘Based For Your Face’ is centred on a Public Enemy sample – a high bar for anyone). Andrew Nosnitsky, who writes the Cocaine Blunts blog, is a long-time supporter of B and argues that appeasing hip hop purists is basically a futile endeavour, because persuading listeners that B can rap ‘properly’ does nothing to aid their understanding of the rest of his catalogue.

In short, Lil B is to hip hop what no wave is to rock: an expression of the breakdown of language and a deconstruction of the genre in a lo-fi, DIY format that rejects the role of major labels. He has described himself as “a rocker in the rap world”, saying indie rock-oriented sites like Pitchfork cover him because they “see the raw emotion”. “You know, everything comes full circle for me,” he tells me. “I don’t consider myself a rapper, you know, it’s just like an emotion, or just a colour or something. It’s something way bigger than hip-hop. So right now it’s just like, I’m just setting my stones right now, and doing what I gotta do.”

Lil B has produced just one mixtape himself, although it’s credited to ‘The BasedGod’. ‘Rain In England’ is a bizarre artefact: 16 tracks, many more than six minutes long, on which B simply talks and talks over a beatless haze of plasticky new-age synth washes, covering every aspect of the ‘based’ life and philosophy (“My brain is a giant forest / Trees growing in it in little circuits,” he ponders).

Did we hear an instrumental from ‘Rain In England’ playing after the show? “Yeah, definitely, thank you so much, man,” he says, pleased to discuss some of the most reflective music in his catalogue. “‘Rain In England’ was the first ambient hip hop album ever. The BasedGod produced it and I was a part of it. It’s definitely just historical, you know, it went over a lot of people’s heads. I mean, no song on there is under five minutes, and I’m rapping just straight, you know, some songs are eight minutes – it’s real deep man, real deep.”

What was the inspiration for the title?

“I was just feeling like that. It was just the whole vibe that I got from the music that I was making, you know? Being outta England, that’s the whole vibe.”

On it, B gives an insight into the subconscious flows and introspection that produced the ‘based’ philosophy, but the specifics are hazy. He’s described being based as simply “being positive, being yourself,” nothing more dogmatic than that, but in the fronting environment of hip hop, with bragging and swagging a chief preoccupation, a few hippy platitudes along the lines of “just be you” and “do what you feel” are noticeably out of sync with the culture. Even if it doesn’t go much deeper than that, it’s an intriguing flipside to the guy who first parks his car, then fucks your bitch.

Devotees who have taken the ‘based’ lifestyle to heart can even satisfy their curiosity with Takin’ Over, the book he’s written to explore “the positive, the love and all possibilities”. Much like St. Paul’s epistles, it’s a collection of text messages and emails to fans offering them guidance and calling for an end to violence and anger in rap music. (You can make your cheque out for $26.99.)

For now though, B’s fans revel in his most playful output, taking up catchphrases like the recurring nonsense boast, “Hos on my dick ‘cos I look like Jesus” (other lookalike options include JK Rowling, Elvis and Miley Cyrus), which rapper Kreayshawn lifted for her own track, the incomparable “Hoes On My Dick”. For every nugget of ‘based’ positivity you’ll find another ridiculous boast, but B’s formal variations, from ‘Rain In England’s’ ambience to the trap rap madness of ‘Realist Bitch Alive’ or the surrealism of ‘Bitch I’m Bill Clinton’, see him emerge as an artist flirting with genre and skirting the boundaries of acceptability.

The music can be read as both lowest common denominator silliness and all-encompassing parody (or at least pastiche), approaching a level of implicit politicisation that’s the exact opposite of up-front politicians like Dead Prez or Immortal Technique. Take the quintessential swag rap of ‘I’m Heem’ – the title refers to Hennessy cognac, yet the lyrics turn ‘heem’ into cryptic babble: “Sex heem, yes heem / I’m heem, naw’mean?” and later, “What I rap for? Everything / Want bling bling and world peace.” You could even muster a comparison with James Ferraro, the underground artist whose 2011 mixtape ‘Bebetune$’ was a hyperreal collage of overblown swag rap, halfway between a love letter and a mockery.

This level of creative freedom points to why mixtapes are more important than ever in hip hop, allowing an artist like Lil B to thrive. Despite releasing an album last year (called ‘I’m Gay’, to the gasps of a genre rife with homophobia), he immediately gave it away on his blog, thus relegating it to a mixtape, and he seems to think his first album is still ahead of him. “I’ve been working on my first album that I’m ever gonna release for about five or six years now, and it’s gonna be worldwide in stores,” he says, but details are vague.

I ask if the transition from mixtape to album will affect the sound or lyrical material?

“Mmm,” he ponders. “I can’t really tell about that… but you know it’s gonna be fantastic, it’s going to be worldwide.” You get the sense that we’ll be waiting for a little while.

Playing by the rules makes for a slow game, and B is more interested in scaling up his operations than dropping an official album and garnering mainstream acceptance. As an artist set on worldwide fame, perhaps he’s considered the staple cash-generators of the hip hop A-list – acting and clothing lines? “I mean, I already been acting,” he says. “I been doing like, some low, low, low key stuff, not putting it out there.”

Ah, of course. But would you want to avoid following in other rappers’ footsteps?

“I haven’t done it now – in everything, I haven’t been doing what other rappers do.”

So there won’t be a Lil B line of Vans?

“Yeah, you know…” He pauses. “I gotta get paid, you know. That’s what it is.”

The mention of Vans alludes to the ratty lace-ups he’s currently wearing – is it true he won’t take them off until he makes a million dollars? “Yes ma’am.” An interesting business plan for a ‘based’ hippy. So how important is money to him? “I mean, from not having it and then getting it, you know, it’s not everything. I see how people treat it and what it is. It’s cool, it’s cool to have it, but it’s not necessary, you know.” So wearing the Vans reminds him to keep working? “To keep it street, keep it street.”

It’s difficult to see how he could work any harder, having made his name basically through relentless prolificacy and self-promotion. You couldn’t ignore that amount of material even if it wasn’t bizarre and subversive too. He knows his history and constantly references artists new and old who inspire him, but he’s taken what he’s learned and binned it. Like the muso who goes punk, believing he’ll find a greater truth in just three chords, B leans on non-verbal or barely-verbal communication to upturn hip hop’s reverence for the spoken word. As the Guardian’s Alex Macpherson points out, “truly brave trailblazing entails trolling your own core demographic.” In that sense, the mere existence of Lil B is to be celebrated, whether or not you want to pump ‘Wonton Soup’ at your house party.

It’s certainly entertaining to see him raise the hackles of old boys like former G-Unit affiliate The Game, who named B “the wackest rapper of all time” after hearing his spot on Lil Wayne’s comeback mixtape ‘Sorry For The Wait’. It’s a shoddy few bars which ever way you cut it, but B’s reaction to the diss was priceless nonetheless: “Game already know he a lesson in my book,” he told a reporter, before blurting, “But he’s irrelevant! BasedGod!” and hopping into a blacked-out Mercedes.

The current wave of young rappers can’t disguise the debt they owe to the Lil B phenomenon, from the cartoonish Kreayshawn to A$AP Rocky, the self-styled “pretty motherfucker” to B’s “pretty bitch”. He doesn’t seem bitter, though. “I’m good, I’m in a great position. None of these artists are really like, jacking me, they’re all fans. It’s all good man, everybody really wants me to win, they rooting for me. I just been doing what I wanna do right now, feeling good being the boss, doing what I want, having not to answer to nobody.”

And that’s the freedom that the lack of a major label can offer?

“You know, we poppin’ like we on a major label right now anyway,” he says. “I mean, the rap game is so good for me right now, so good.”

Lil B madness reached a tipping point when Justin Bieber was seen doing B’s trademark cooking dance last year (instructions: pretending you’re cooking). He was returning the favour after B named a song after him and declared them to be cousins, but now Bieber’s taken it a step further – check out his latest issuance of product, ‘Boyfriend’, with its intro chant of “swag” in his Timberlite tones. Is it time to come up with a new buzzword?

“I mean, I always stay making the trends,” says B, “but you know right now, that’s my bruh, Justin is good, man. I heard myself in his new song and it’s like, that’s love man! So it’s great, it’s all family.” And now a whole new demographic is in reach. “Yeah, I got a lot of young fans already.”

Other seemingly inappropriate creative plans include his “garage punk” album, ‘California Boy’. All that’s known about this one is that it’s “not some joke rock album” and is inspired by Lenny Kravitz and Axl Rose. Even his hip-hop collaborations seem wildly unlikely, with recent tweets suggesting a hook-up with enigmatic rap genius Jay Electronica. “Yeah, me and Jay gonna hook up, I’ma be definitely rockin’ with Jay Electronica soon. We were supposed to meet up while I was out here but our timing’s been messed up.” Jay’s notoriously low output rate seems an unlikely fit with B’s work ethic, not to mention his complex wordplay and Nation of Islam references. “I think we’re really the same,” counters B. “It’s just, you know, Jay Electronica is not really wanting to work with anybody, he’s not just reaching out to people saying, ‘I wanna do a mixtape with you’ or something. But you know, we all from the same pot.”

For all the world domination plans, it’s still hard to see how Lil B can ever truly commercialise his underground success. He didn’t manage to sell out XOYO, for one thing – an 800-capacity venue – and of course his record sales are irrelevant. As we wrap up, having nabbed little more than 15 minutes with him, B poses for photos and switches it on perfectly, lowering his shades here, flashing his grill there. His manager dials the numbers on his paper plate and politely hurries us along.

A pretty lo-fi operation on the material level, but in the virtual realm the BasedGod is someone else completely – Twitter mogul, YouTube star, self-help guru and record label boss (since he signed his own cat, Keke, to BasedWorld Records). He’s pissed off the old guard and led in the new. He’s even lectured at New York University (“my first sold-out lecture and my first lecture ever,” he notes), and all without a major record deal or heavyweight management. You can see why he’s convinced of his own genius, even if half of XOYO weren’t so sure. B reaches out to hip hoppers, baby-faced tweens, Pitchfork geeks, broadsheets, arch intellectualists and even the university establishment.

His hopes for his eventual legacy to hip-hop are no less universal. “Just become the BasedGod and do what I need to finish,” he says. “I need to just do a lot of work and there are a lot of goals that I need to complete so that I can feel happy and my supporters can be happy.” All that’s left to say is thank you, BasedGod.