There’s a great video series on YouTube called What’s in My Bag, produced by legendary Los Angeles record store Amoeba. The premise is pretty straight-forward: each episode, a musician rifles through the racks and chooses some stuff, heads to the till then sits down to explain what they’ve bought – and why.

One recent edition saw an appearance by Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, along with writer Amy-Jo Albany. Halfway through, the famous bassist pulls out a clutch of J Dilla records. “I just love J Dilla. I think he’s an absolutely transcendent, phenomenal musician,” he says, shuffling through some vinyl.

Eventually Flea picks out one record in particular. “I listened to this record – this ‘Ruff Draft’ record – when I was in Big Sur by myself. I had headphones on and I was walking around on this trip through the hills and the mountains. It just like…” Tears start welling up in Flea’s eyes as he continues, voice trembling. “It touched me so deeply, and I remember I couldn’t stop crying, it was so powerful and like…” He scrunches his eyes tight shut, bows his head and pats the record, hard. “I really love this a lot,” he eventually says, triumphantly, smiling through the tears.

Finding any art that touches the soul so deeply is rare enough, but finding hip-hop music that does the same is rarer still. Today, ten years after dying of a blood disease, the emotional reverberations from the productions of James Dewitt Yancey are still being felt. Musicians often share a similarly powerful reaction with Flea: Jack Barnett of These New Puritans sometimes wears a “J Dilla Changed My Life” t-shirt on stage, which is also the name of an annual club night in London. Tributes over the past decade have come from hip-hop artists like Kendrick Lamar and De La Soul through to jazz pianist Robert Glasper and many, many more besides.

Yet for all the adoration and respect from fellow artists, J Dilla has remained something of a cultish proposition, his influence primarily refracted through the music of others instead of directly felt. During his lifetime, Dilla – also known as Jay Dee – worked behind the scenes producing big hitters of the day: people like Janet Jackson, A Tribe Called Quest and Pete Rock. His own music, though, made as part of super group Slum Village and later by himself, never made a serious commercial impact, although 2006 record ‘Donuts’ remains a cult classic for real hip-hop heads.

Eothen Alapatt was the general manager of J Dilla’s record label, Stones Throw, from 2000 and 2011 – also home to people like MF DOOM. Now he’s the Creative Director of Dilla’s estate and determined to carve out a fresh audience for his deceased client and erstwhile friend. “There are some people who channel a deeper, spiritual element through pop music,” Alapatt says on the phone, his enthusiasm palpable from the other side of the Atlantic. He reels off a list ranging from Dylan to Coltrane. “We come across them once in a while and it just becomes this profound, moving experience once you’re indoctrinated into the way they channelled that energy. People like Dilla speak, not just to the educated but to the everyman.”

To that end, Alapatt has revived Dilla’s own record label, Pay Jay Productions, and is gearing up for the long-delayed release of ‘The Diary’, the final LP recorded during Dilla’s lifetime. Originally supposed to drop in 2002 but shelved and embargoed under controversial circumstances, the LP is finally getting released on April 15 this year, painstakingly assembled from two-track mix-downs and multi-track masters found in Dilla’s archives after his death in 2006.

Getting the record released represents a triumph of dogged loyalty to Dilla’s legacy in the face of all-but-insurmountable challenges. Towards the end of his life and facing death, Dilla entrusted Alapatt with archival duties across his vast corpus of work. Over the years that followed the producer’s passing, he found himself smothered in red tape, paying tens of thousands of dollars to navigate law suits and sacrificing working relationships as he set about figuring out a way to get ‘The Diary’ into the hands of the public.

Now finally facing release, with guest vocal appearances from the likes of Snoop Dogg and additional producer credits going to Madlib, Pete Rock, Hi-Tek and House Shoes, Alapatt hopes ‘The Diary’ is as close an approximation as possible to what Dilla himself would have put out 14 years ago. “When Dilla stopped working on the record he had done multiple revisions of the tracks,” Alapatt says. “I was able to go through and piece together what were the latest versions that he recorded. To me, that’s an obvious and telling answer to the question of what Dilla wanted to do. He was a meticulous revisionist.”

Slotting into Dilla’s discography right between his earlier, smoother-sounding productions and his harder latter-day material, ‘The Diary’ is the sound of an artist at a crossroads. Nowhere is this more apparent than the two consecutive versions of ‘The Shining’ early in the record; the former a club-ready, bright-lit banger, the latter a murky sampling showcase and the proverbial other side of the coin. Whatever phase of Dilla’s career resonates most with fans, there is much to be mined here.

For Alapatt, it’s also as good an entry point as any for the uninitiated. “I really feel like this album is a chance for us to point a focused beam of light on this man, his life’s work, his catalogue and his story,” he says. “Hopefully it’ll take off from there.”

By all accounts, James Dewitt Yancey was already a musical prodigy when he was born on the east side of Detroit in 1974. The eldest of four children with a sister (Martha) and two brothers (Earl and John), Yancey built a deep knowledge of music through his parents (his father a jazz bassist, his mother a former opera singer), absorbing everything from Slave to Jack McDuff. Able to match pitch-perfect harmony at two months old according to his mother, by the age of two years old he was already collecting and listening to vinyl at a voracious rate.

During his teenage years he formed a rap group with friends – Slum Village – after they bonded over a mutual love of rap battles. At night, Yancey would sequester himself in the basement alone, endlessly perfecting beats with a basic cassette deck. In 1992, he managed to acquire an Akai MPC sampler through Detroit musical connection Amp Fiddler, a session keyboardist who had worked with Prince, Parliament, and Enchantment. Fiddler taught Dilla how to use the MPC and soon Yancey was off and running as Jay Dee, his first moniker.

Word of his talents travelled fast and by the mid-nineties Dilla was fielding calls at home from household names like A Tribe Called Quest and Busta Rhymes. In 1996 the former were nominated for a Grammy with ‘Beats, Rhymes and Life’, which Dilla had gone on to produce. The emerging beat-maker distrusted the media circus surrounding the whole thing; Tribe rapper Q-Tip would later recall the difficulty of persuading him to attend the ceremony.

In 1997, Slum Village released their debut EP, ‘Fan-Tas-Tic (Vol. 1)’. Its mix of smoothed-edge keys and scratchy soul samples wasn’t without its familiar charm but the real attraction was the beats: an unhurried, shuffling mix of inventive sampling and Dilla’s skilful programming. The record resonated well with fans of Detroit hip-hop and also gained the attention of Q-Tip, who championed them as successors of the socially conscious A Tribe Called Quest.

Unfortunately, it was a label that the producer himself absolutely detested – a total misrepresentation, he said, of what he and his group had intended. “I guess that’s how the beats came off on some smooth type of shit,” he later admitted. “And at that time, that’s when Ruff Ryders [were out] and there was a lot of hard shit on the radio so our thing was, we’re gonna do exactly what’s not on the radio.”

Dilla later enjoyed commercial success with ‘Amplified’, the debut solo record from Q-Tip, but it wasn’t until his own album, ‘Welcome 2 Detroit’, in 2001 – the first to be credited to J Dilla – that he finally delivered a record entirely on his own terms. Booming funk is melded with bossa nova, krautrock and whatever else the producer was into at the time, making for a collection of songs whose unifying characteristic is their individualism. It’s a record nobody else could have made, and also one of the core entry points to his catalogue.

Unsurprisingly, Dilla’s invaluable combination of mainstream production prowess and legitimate underground credibility led to calls from major labels. After a second record with Slum Village, Dilla left the group to sign with MCA Records that same year. “When he got signed to MCA, he was a hit-maker,” Alapatt tells me. “When he signed a deal with Universal Music Publishing too, his catalogue was worth millions of dollars – because the records he produced were all platinum records.”

Yet rather inauspiciously, the producer came into conflict with his new label almost immediately. After producing an entire record for Detroit hip-hop duo Frank-N-Dank, Dilla was asked to re-record the whole album with fewer samples, to make it more commercial-sounding. Dilla obliged but neither version of the record was released.

Undeterred, Dilla set to work on his next, as-yet-untitled solo LP the following year, again keeping the sampling to a minimum in what was possibly a nod to commercialism. Dilla decided to perform MC duties on the record, doling out production to Madlib, Kanye West and others. “He was way ahead of the likes of Timbaland and Pharrell in terms of bringing a real funk sound, synthesisers and programmed drums to his music,” Alapatt argues. “But this is a guy who straddled a fine line between the underground and the commercial. Dilla’s given a deal to do whatever he wants for MCA, so you can imagine that there’s going to be a meeting [of those different sides of himself]. That’s what happened with this record.”

Once again, MCA weren’t impressed and shelved it, this time for a host of reasons ranging from personnel changes through to alleged scheduling conflicts. Dilla spent the next year or so, on-and-off, tweaking the record and oscillating between a rougher, more underground edge and a more commercially-led sound. It didn’t matter – the record was held in seemingly perpetual abeyance and Dilla was eventually dropped by MCA.

Alapatt started working with Dilla during the album’s ill-fated production and for the remainder of the producer’s career while at the helm of Stones Throw Records. “I couldn’t believe he was working with us,” he remembers. “From my perspective we were small potatoes and this guy was the real deal. I only imagine this now because I’ve had a long time to think about it, but it must have been a traumatic experience getting dropped from MCA after so much had been given to him and so much expectation had been levied on him.”

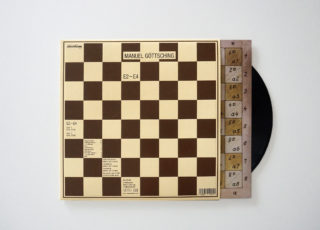

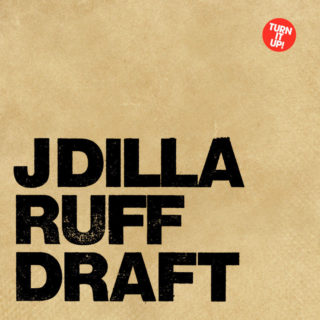

Dilla poured his frustrations with the MCA experience into ‘Ruff Draft’, an EP put out quietly and exclusive to vinyl by German independent outfit Groove Attack in 2003. The release marked a major shift in focus and for some – like Flea – it’s the best thing he ever recorded. “It’s the biggest fuck-you he could have possibly given to the commercial music industry,” Alapatt laughs, approvingly.

Eschewing commercial considerations entirely, ‘Ruff Draft’ is totally uncompromising. “This one is for the real niggas out on the roll,” he raps on ‘Reckless Driving’, its walloping beats-and-bass combination almost leaving you out of breath by the track’s sudden end. “We’re off the chain,” he shouts into the mic, like a man indeed finally unshackled. From this point onwards Dilla began to exhibit a totally different, much rougher-edged side to himself.

Dilla’s chastening experience with MCA certainly presaged the producer’s sharp change in direction but another catalyst was his worsening health and perhaps growing sense of mortality. After moving out to Los Angeles and collaborating with fellow producer Madlib, his illness – a rare blood disease called thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura – worsened considerably. Dramatic weight loss left no option but to go public about his condition in 2004, confirming months of speculation.

By November 2005, Dilla was performing on his tour of Europe in a wheelchair and the severity of his illness became clear. Finally, on 10th February 2006, James Dewitt Yancey died of cardiac arrest at home with his mother by his side. He was just 32 years old.

Three days before his passing, Dilla had managed to release one final recorded statement – ‘Donuts’. An instant classic and a fitting epitaph for a near-imperious production legacy, the instrumental, beautifully strange LP was pieced together from samples while the producer was literally on his death bed. As one reviewer noted in a retrospective review, its skittish stop-start sequencing and time signatures, scattershot tension and patchwork of melancholic soundscapes, point to an artist who knew he was running out of time.

In an entry for the respected 33 1/3 book series on the LP, author Jordan Ferguson suggests that ‘Donuts’ in fact isn’t a hip-hop record at all. “It’s hip-hop as musique concrete,” he says. “Even knowing all the sample sources doesn’t make the sounds any more discernible in one’s mind… No, ‘Donuts’ is a game of resonant emotion, a mind meld between its maker and the listener.” It is at its core, Ferguson says, a record about death and dying; an exercise in self-reflection on mortality.

Knowing all of this makes hearing ‘Stop’ – with its sweeping strings and Dionne Warwick refrain: “You’re gonna need me, you’re gonna want me back in your arms” – all the more harrowing. It also makes listening to ‘Donuts’ and the rest of the Dilla cannon even more essential. Just ask Flea.

The Diary

The Diary

Oft-bootlegged throughout the 14-year wait for its arrival, Alapatt’s meticulously-crafted release of ‘The Diary’ might not match some die-hard fans’ preconceptions but there’s no arguing that it’s the definitive version of Dilla’s long-lost LP. Its 14 tracks pinball between the bass-heavy funk and minimal rhythms that would inspire Pharrell Williams (‘Fight Club’, ‘So Far’), and the scratchy, uncompromising sample work for which Dilla would become a hip-hop icon (‘Fuck the Police’, ‘Drive Me Wild’). As a record that straddles two distinct phases of Dilla’s career, some songs will land better with fans than others but all make for essential listening.

Ruff Draft

Starting off as an obscure, vinyl-only EP released exclusively in Germany in 2003, ‘Ruff Draft’ was posthumously expanded into an LP’s worth of material in 2007. Representing the apex of Dilla’s fearless repudiation of commerciality after he was dropped by MCA, the record makes no allowances and brooks no compromise but is all the more compelling for it. Most tracks clock in at no more than two minutes or so but it doesn’t matter: each one makes its mark like a drive-by shooting. ‘Reckless Driving’ is probably the hardest thing Dilla ever recorded – its sheer power remains unmatched even today.

Donuts

Recorded on the producer’s deathbed and released three days before his passing in 2006, ‘Donuts’ is the point in Dilla’s oeuvre at which his music transcends hip-hop and becomes high art. Its 31 instrumental tracks abruptly start and stop, snipped seemingly at will by a man perhaps reflecting on the premature end to his own life. Some of the samples are obvious, others oblique but none have been so masterfully woven across a record before or since. It’s a truly sublime parting gift from one of the greatest producers to have ever lived and the bible for students of sampling.