“It’s Earth music”: Khruangbin and Vieux Farka Touré on their dynamic new collaboration

The American psych trio have teamed up with the 'Hendrix of the Sahara' on their latest record

The American psych trio have teamed up with the 'Hendrix of the Sahara' on their latest record

Khruangbin call from Boise, Idaho. It’s a state known for its beautiful, vertigo-inducing mountains, a neverending landscape, and of course its agriculture – it’s the number one producer of potatoes in the United States.

It’s fitting that this evening they will play a sold-out show at the city’s Botanical Gardens. Most touring bands are used to playing grubby-cum-charming purpose-built venues and live on the diet of hummus, carrot sticks and other miscellaneous crudite; not so glamorous. It’s important to earn these stripes – Khruangbin still play venues like this – but gracious to be afforded a welcome break from them too.

After all, they’ve just returned to the USA from Europe where they played and litany of sold-out headline shows and standout festival performances at the likes of Spain’s riotous Primavera Sound, Glastonbury’s rural farmland and as headliners at Cross The Tracks, held in Brixton, London’s populous, multi-ethnic epicentre.

“The festivals were highlights of the tour, everywhere had a different vibe and [Cross The Tracks] was way bigger than I thought it was going to be!” says lead singer and bassist Laura Lee, in-keeping with her air of humility. “Touring will always be hard in some sense, but if you’ve paid your dues it does get nicer,” adding once more: “[Boise] is gorgeous.”

In the past few years, Khruangbin have gained legions of fans around the world. Having released their debut album The Universe Smiles Upon You in 2015, it was the second album, Con Todo El Mundo (2018), released on the hugely successful independent label Dead Oceans, that truly caught the attention of music fans worldwide. Their next releases, Morchechai (2020), and most recently two collaborative EPs, Texas Sun and Texas Moon, with neo-soul artist Leon Bridges (an ode to the artists’ home state), charted in the top 50 both the UK and US. It marked a culmination of supernatural talent and ten-plus years of hard graft.

It’s not so often that artists like Khruangbin, reach these commercial inclines. Often described as ‘world music’ (more on that controversial term later), they genre-blend generously merging influences from Thailand (in their earlier music), Korea and the 1960s and ’70s psychedelic funk of the States, the latter being evident in their breakout track ‘Everyone Finds the Third Room’. Part of their success may be down to the fact that they’re not intimidating; the reputation of musicians and fans with such far-reaching knowledge of subversive genres is that they’re High Fidelity-style know-it-alls who like testing your knowledge and disposing of folks who can’t reach the mark. But Khruangbin’s mentality feels more ‘come one, come all’; they’re not just musicians, but willing, welcoming and persuasive educators. It’s a mindset that runs through the fabric of the band, which is what makes them so convincing.

“Each one of us has knowledge of specific genres of music,” says guitarist Mark Speer, the band’s crate-digging obscurity specialist. “Then there is a Venn diagram where all of these things come together.” This is the key to Khruangbin – their differences in taste, personality and even opinion enhance the variety in their music. It feels like a no-judgement zone; it’s apt that before they were a band they were friends, laying a foundation to comfortably explore with one another.

“It’s not anything that’s forced, it’s by design,” says drummer Donald ‘DJ’ Johnson. Naturally then, this unforcedness emanates to audiences – and that is intentional. “We use the difference in us as a band to bring together differences in our audience,” says Johnson, noting that their audience intersects in multiple diversity lines from age, sex, race and culture.

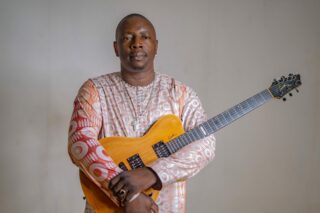

All this leads us to how Ali, Khruangbin’s new collaborative album with Vieux Farka Touré, came to be. The son of the revered Malian musician Ali Farka Touré, who passed away in 2006, Vieux was looking for the perfect collaborators to continue spreading his father’s work.

At the peak of his influence, Ali was dubbed the African John Lee Hooker, integrating African American Mississippi blues with the language and style of Malian music to create what came to be known as desert blues. Now, Vieux is a musician in his own right, but for years he was reluctant to become one, wary of the weight of expectation.

“It’s difficult to follow in the footsteps of someone who has been to the top of the mountain,” he told Songlines earlier this year. Developing the confidence and forging his own identity produced fruitful results which earned him his own sobriquet: The Hendrix of the Sahara. The pipeline from John Lee Hooker’s blues to Jimi Hendrix’s rock and roll is apparent, but the distinction between the two artists resulted in Vieux being respected in his own right, and sealing the approval from the public he so craved.

Vieux’s vision of Malian music was always steeped in sky blue thinking with a view to globalise it. He chose to use the Western artists as a vehicle to spread the music of his people. He performed with Alicia Keys and Shakira at the 2010 World Cup in South Africa (though socio-political allegiances like these have a short shelf life), and has since worked with the likes of Dave Matthews and John Schofield.

Now 40, he’s in the mood for retrospective thinking, and he’s not the only one who has been. In the past decade, the appetite for African music has grown exponentially in the west. Of course, legacy African artists like South Africa’s Miriam Makeba and Nigeria’s Fela Kuti, and Ali himself, have reached a certain level of notoriety and recognisability outside Africa (the former partly due to her marriage to the African American civil rights activist and leader of the Black Panther Party Stokely Carmichael), but better accessibility – mediated via online exposure, regular collaboration and constant work – has accelerated this recognition in the past couple of decades. Think Damon Albarn’s Africa Express, the unlikely surge of the music of William Onyeabor in 2014, Tinariwen, and labels like Awesome Tapes from Africa.

Jumping on this wave, around 2019, Vieux sought to reinvigorate his father’s legacy. The record would always be a two-artist collaboration album, but with who? Off the back of Con Todo El Mundo, Khruangbin had begun playing to larger and larger audiences and had caught the eye of Vieux’s manager. On top of their success, crucially, they are a young band, with a viable currency that appeals to a younger audience, unlike the more established artists he’d worked with before. After seeing them live and being impressed by their musicianship, he was sold. “I was impressed by their London show and their ability as musicians. I knew we’d make a special record together that honoured my father.”

Khruangbin agreed: there was a sense of importance in doing the record, and fitted with the ethos of the band, it felt like them. It’s not that there wasn’t slight trepidation; in fact, ironically there was a sense of imposter syndrome most often felt by those like Vieux who don’t ‘fit’ into the image of the western world, was teeming within them. “He works a lot faster than we do” says DJ, “and we’d wonder ‘Did that sound ok? We only did two takes!’”

At times he’d hand the baton over to them and say, “You know what to do”, and they’d covertly look at each other with question-mark eyes. Vieux’s take on recording is endearing, showing the trust he had in the band as artists even when they may not have felt it internally. “We would play around a little bit with it, then push record and voila!” he says.

If the record is anything to go by, they certainly did know what to do. Put simply, Ali is a stunning body of work. Lead single ‘Savanne’ has an air of suspense; the track’s smoothness goes through your body in the form of a deep bassline, meandering guitar and the gentleness of Vieux’s sung and spoken words. Vieux’s particular favourite interpretation on Ali is ‘Tongo Barra’. “It is so funky and different from the original, and such a nice blend of Malian and American style.”

The album does feel like a harmonious and synchronised blend. Despite the obvious distinctions between the work of Khruangbin, Vieux and Ali’s work, it’s difficult, if not impossible, to tell where these musicians as individuals begin and end.

This sense of harmony is an extended metaphor for how both Khruangbin and Vieux want Malian, African and other forms of music to meld: they want to make world music, that is actually world music, in that it’s experienced as something that is expansive rather than cordoned off to wily white record collecting obsessives or oxymoronic ‘world music’ categories in major American award shows.

“It’s an old and dated term,” says Vieux. “I mean, my music is much more closely related to American rock, blues and funk than anywhere in, say, parts of Asia and even parts of Africa. Either you should just call music, music or be more specific as to where it’s from – [otherwise] it disrespects the diversity of music outside of the west.”

Despite this suggestion, Vieux adds that he doesn’t really know the solution to this linguistic problem, but as westerners themselves (though the members of Khruangbin are diverse in their own right), they’re doing their bit to make sure artists that they work or come into contact with are properly credited. They use their significant platform to shine a light on talent from around the world; for example, the album artwork for Ali is by Malian artist and contemporary of Ali, Abdoulaye Konate.

We speak a little about the recent successes of commercial African artists like Burna Boy, Tems and Uncle Waffles and Hispanic artists like Bad Bunny and Ozuna – is this perhaps a sign of progress?

“It does feel like everything is slowly opening up,” says DJ, “and people are realising that there are gems everywhere.” In their own discussions, Khruangbin have changed the expression of all music to ‘Earth music’, a term that may appear similar to, but crucially doesn’t have the baggage of, ‘world music’. “It’s Earth music because we’re all here,” Lee exclaims.

You don’t have to physically be there to feel and be moved by Earth music; the beauty of it is that it entices curiosity far greater than the arbitrary labels that have far too often divided and dampened how we experience culture. After our interview, Khruangbin will go on to play their brand of Earth music in Idaho, greeting an audience which has been relatively under-exposed to non-western artists. When they tour Ali across the world with Vieux, they’ll introduce the masterful work of one of Africa’s most lauded musicians to a variety of people who will experience the essence of music before its genre, and hopefully find something that resonates with them in spite of the distance and time.

“My father was a very important figure in Mali. He is a big source of pride and inspiration for the people there,” says Vieux. “My responsibility is to take care of his legacy and move it forward to the next generation and I hope that with Khruangbin, I can spread it even further around the world.”