Inspiration Jamboree: The story of Beat Happening

Just how confrontational Beat Happening were is almost forgotten as frequently as their influence on true indie rock. Calvin Johnson recalls a life in the shade

Just how confrontational Beat Happening were is almost forgotten as frequently as their influence on true indie rock. Calvin Johnson recalls a life in the shade

“Implicit in Beat Happening’s music was a dare: If you saw them and said, ‘Even I could do better than that,’ then the burden was on you to prove it. If you did, you had yourself a band, and if you didn’t, you had to shut up. Either way, Beat Happening had made their point.”

Of all the groups profiled in Our Band Could Be Your Life, Michael Azerrad’s crucial survey of the key players in 1980s American underground rock, Calvin Johnson’s ramshackle outfit could well lay claim to being simultaneously the most influential and least-known of the lot. Crammed into the tail-end of Azerrad’s book following on from chapters about luminaries of the era like Sonic Youth and Black Flag, the presence of Beat Happening might seem generous, even entirely incongruous.

Yet anybody with a working knowledge of indie music’s early years stateside will understand that the seismic impact on the fledgling scene made by Johnson, Heather Lewis and Bret Lunsford means that the trio fully deserve their place in the pantheon. Essentially starting an entire movement from Johnson’s unfashionable hometown of Olympia, Washington – where he lives to this day – Beat Happening dared to hold a mirror to punk and challenge its prevailing machismo orthodoxies, ultimately helping to pave the way for everybody from Kurt Cobain to Sleater-Kinney.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of Beat Happening’s totemic self-titled debut. Even if you’ve never heard the record you’ll recognise its distinctive bright yellow cover and crude crayon drawing of a cat in a rocket ship, a fitting representation of a combination of ambition and affected innocence. In celebration of just how far that little rocket travelled, last month the album gained an entry in Bloomsbury’s 33⅓ series of profile books on canonical records.

Considering the band could barely play their instruments when they recorded ‘Beat Happening’, could Johnson ever have conceived people writing books about it back then? “Well, it wasn’t my idea to write these books,” he says slightly defensively over the phone from his Olympia home. “On the other hand, I just assumed when we were making these records that they were classics. I didn’t see any point in making them if they weren’t going to be. I always felt that music should be timeless. I mean, I appreciate music of the moment and pop music – I love pop music – but I also feel that what we excelled at is creating songs that just stand alone.”

Testament to that fact is ‘Look Around’, a long-overdue, career-spanning double LP anthology set to be released by Domino next month, with songs hand-picked and chronologically sequenced by the group from 1984 debut single ‘Our Secret’ right up until 2000 anomaly ‘Angel Gone’, released after eight years of inactivity. “They’re the songs we thought would be a good collection and representation of what we do,” Johnson offers, simply.

Taking in influences ranging from the Cramps to Young Marble Giants, one of the most striking things about the weird and wonderful 23-track collection is the aesthetic consistency from the first track to the last. Sure, fidelity improves working through the songs in chronological order and the compositions become gradually more ambitious but the music itself remains a study in lo-fi simplicity shot through with sexual tension; a template that would be followed by Sebadoh, Pavement and any number of other Portastudio-wielding followers. Guitar lines are uniformly straightforward, drum rhythms less-than-rudimentary and bass guitar absent altogether. “I don’t know whether it was intentional though,” says Johnson. “We just didn’t have a choice. We made music that we made – and that’s just the way it is. We were always working to the edge of our abilities.”

Calvin Johnson was born 1st November 1962 in Olympia. By the age of 15, he was already volunteering at his local community radio station, KAOS-FM, operating out of the Evergreen State College nearby. The station’s music director, John Foster, took Johnson under his wing, becoming his mentor. Foster championed independent music at KAOS, reportedly insisting that 80 percent of music for broadcast had to have been released on independent labels. He also founded an independent music magazine, Op, which was to become a key point of exposure for the local cassette release scene.

Johnson immediately embraced Foster’s socio-political view of music and his circumvention of the mainstream. Eventually, he landed a weekly slot on air playing punk and through his show, the teen discovered UK post-punk and key Rough Trade signees like the Raincoats, Delta 5 and the Slits; female-fronted bands concerned more with making interesting music than guitar theatrics. Following on from a temporary relocation to Maryland for his senior year at high school and an introduction to the bourgeoning punk scene there – and a chance encounter with Minor Threat front man Ian MacKaye – Johnson resolved to start a label: K Records. The scene was set for Beat Happening’s arrival.

Heather Lewis moved into the frame when her own band had their first cassette put out by Johnson, who was by this point already playing in a couple of groups and something of a celebrity around Olympia thanks to some fearless performances and a curious penchant for 1960s retro-kitsch. On stage, Johnson had taken to fey theatrics like rubbing his belly, raising his hands to his shoulders and tugging on his too-tight t-shirt.

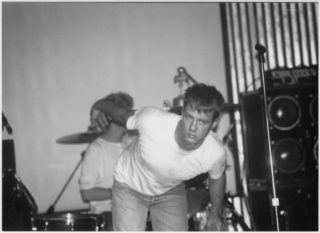

He and Lewis soon started playing together in yet another outfit – Laura, Heather and Calvin – who just so happened to play a show in front of one Bret Lunsford. “That performance was so riveting,” says Lunsford in Our Band Could Be Your Life. “It was amazing how naked the band let themselves be and yet normal at the same time – as much as you can say that Calvin onstage is normal.”

Influenced by the Beat movement of the 1960s – taking their name from Beatnik Happening, a student film produced by Johnson’s girlfriend Lois Maffeo – and punk in equal measure, the trio begun playing shows in kitchens and living rooms before recording a four-track tape with friend and Wipers leader Greg Sage. The playing was endearingly haphazard but the songs were strong – an amalgamation of punk’s simplicity and ’60s surf melodies – and Beat Happening was born.

In Olympia at least, Johnson and his bandmates were at the head of a scene that fetishised fey, late-fifties and early-sixties sensibilities and held adulthood in abeyance, with pyjama parties and meeting up for afternoon tea not uncommon (along with liberal behind-closed-doors sexual shenanigans). By March 1984, an all-ages punk club called the Tropicana had opened downtown and the scene finally had an epicentre. One show at the venue even saw Beat Happening support Black Flag. By the following year, though, after near-constant harassment from local rednecks, the venue was closed. Indeed, while Beat Happening might have been at one with a few local kindred spirits, wider America was disinterested at best or even openly hostile, Johnson says.

“Teenagers in America were not interested in punk rock. They paid no attention to it whatsoever. It was only older people that were into punk. When we were getting started, mainstream America was still just starting to process punk through things from bands like Talking Heads or Blondie that became pop hit records or whatever. Overall though, America still hadn’t really absorbed the shock. So we were playing music to people who had no perspective. To them, we were just bad and they were just like, get out of our way.”

Johnson has always been at pains to get this across. Interviewed in a French fanzine back in 2001, he laboured the point: “I don’t think people understand the level of animosity that Beat Happening attracted through most of our time performing live. This concept that we were this performing group that were some kind of – I don’t know – shy pop… Our performances were clearly confrontational.”

The big challenge for Beat Happening was that by the time they started, even punk ceased to exist as a cohesive bloc against the mainstream. “Punk had become hardcore but hardcore itself was already kind of over in a way,” Johnson remembers. “I mean, it never died but the initial burst of hardcore had faded quite a bit and by you know, ’85, there were just all these terrible bands being hardcore and it was just depressing.”

Meanwhile, lo-fi, sixties-stylised punk didn’t belong to any sort of recognised genre, which might afford it a degree of protection or significant interest – at least at first. “I felt we were like [some other bands] in certain ways,” Johnson tells me. “Like ‘Oh, we’re kind of garage-y,’ but the garage bands just totally weren’t interested in us. And then, you know, ‘Well we’re kind of psychedelic,’ but the psychedelic bands ignored us. We weren’t ever enough of anything for any of those to notice us.”

Of course, in many ways it didn’t matter. Beat Happening had never set out to be famous, other than during a comically ill-fated sojourn to Japan in 1984 (although all wasn’t lost: Johnson discovered Shonen Knife and brought their records with him back to the States). So long as K Records existed and Johnson was able to release music from his own band, others around town, and beyond, that was enough.

1988 saw the release of ‘Jamboree’, self-described as “dark and sexy” by Johnson and a record beloved of Kurt Cobain – the late legend listing the record in a famous list of his 50 favourite albums. So enamoured was Cobain with Johnson and the Olympia scene, in fact, that he had the K Records logo – an amateurishly-drawn “K” in a shield – tattooed on his arm. Not for nothing did Johnson once proclaim to a fanzine: “We are Beat Happening and we don’t do Nirvana covers. They do Beat Happening covers!”

A breakthrough album, its standout – ‘Indian Summer’ – became an indie touchstone, covered by everybody from Dean Wareham to Ben Gibbard (who described it as “the indie Freebird,” no less). Pitchfork names the track as one of the very best of the 1980s. ‘Jamboree’ was also the first of two co-releases with Rough Trade (although by all accounts Beat Happening didn’t receive the red carpet treatment that people like the Smiths did).

All the same, Beat Happening were only ever going to operate at a certain level. “Our music was still hard for people to absorb,” Johnson says. “Most people doing music on an indie level or like a small level like we were, were really trying to be much more normal, like Van Morrison or whatever. So more of the context we were seeing a lot in the early/mid-eighties was that we were playing music with people who were trying to be big rock bands, or singer-songwriters or whatever. We just weren’t seen as being that level.”

Another album – the darkly aggressive and rougher-hewn ‘Black Candy’ – arrived the following year, though even modest success was still elusive, says Johnson. “It was only when Sub-Pop released ‘Dreamy’ in 1991 that people started be like, ‘Oh wait a minute.’ Before that it was just a few weirdos here and there.” It helped that ‘Dreamy’ represented the beginnings of a slightly more polished approach. Ragged minimalism is still the order of the day, but the songs are gorgeous, Lewis’s wistful romanticism the perfect foil for Johnson’s tougher posturing. “A stunning return to form,” as one review raved.

Around the same time, a glut of hitherto independent artists were being swallowed up by major labels. The Replacements had long since signed to Sire, then Sonic Youth made the jump to Geffen in 1990, famously followed by Nirvana in time for the release of ‘Nevermind’ the following year. “The ’80s and the ’90s are like worlds apart,” Johnson observes. “In the ’80s there was the mainstream and the underground and they had nothing to do with each other. The ’90s had the strange crossover and it was very surreal.

“For us though, it wasn’t an option. We were doing our thing. You know, people always ask that question, like, ‘What if they offered you a million dollars? Then what would you do? THEN what would you do?’ And it’s like, well no major label ever did or ever would! We are just an underground pop band.”

Instead, Johnson and company celebrated their roots with the inaugural International Underground Pop Convention – inspiration in part, no doubt, for Waynestock in the second Wayne’s World film. K Records had been running an ‘International Underground’ series of releases for artists from abroad and, for Johnson, a festival was the next logical step.

Says Johnson: “We had been working with bands from all over the country and Canada, England and places, and I just thought, why don’t have an event? Instead of being on tour when you just pass each other in the middle of the night, why don’t we all just hang out for a week? So it was a convention for people who were interested in this kind of music.”

Few expected it to succeed, as Johnson admitted in a previous interview, stating: “It was sort of an audacious idea of doing something like that. We had hardly sold any records ever, and no one had ever cared much about anything that we did. It just seemed like if just the people who made the music showed up, that would be a success.”

The line-up reads like a roll-call of early-nineties indie rock royalty: The Melvins, Jad Fair, Nation of Ulysses, Fugazi, L7 and of course Beat Happening themselves. Though the convention largely took place in and around Olympia’s Capitol Theater, its reverberations were felt far beyond the sleepy town’s perimeter. The first night of the event – a set of shows by female punk and queercore bands playfully entitled ‘Love Rock Revolution Girl Style Now’ – was fundamental in birthing the entire riot grrrl feminist punk movement. Cobain – on tour with Nirvana at the time – was reportedly deeply upset to have missed out. Spin named the whole affair “the true Woodstock of the ’90s.”

Elements of the convention also felt as though they’d been pointedly differentiated from typical corporate rock equivalents. Seminars, booths and panels were eschewed, while invitations even included a disclaimer: “No lackies to the corporate ogre allowed.” Yet Johnson is adamant that the convention wasn’t meant as some sort of direct affront to major labels.

“We exist in our own world. We don’t exist in a world where the majors exist,” he says, almost exasperatedly. “They’re not in our mind and we’re not even thinking about that. We’re not thinking, what can we do to piss off Warner Brothers? We exist in the world of K and that’s enough – that keeps us pretty busy.”

Beat Happening weren’t too busy to release more music, though. 1992 brought the arrival of their seventh and final album, ‘You Turn Me On’, again in partnership with Sub-Pop. The record saw the threesome stretch beyond the template they’d established: multi-track recording was employed for the first time and one track – ‘Godsend’ – clocks in at more than nine minutes long. “Starting with making music or being involved in music, you have a million ideas and you can’t do them all at once,” Johnson says of the record. “Sometimes it takes a little while and now you know, 35 years later I’m still working through some of them. So there wasn’t a feeling like we had to escape [our previous style]. It was more like, now what can we do?”

Produced by Stuart Moxham from Young Marble Giants, contemporary reviews heralded ‘You Turn Me On’ as a dream-pop masterpiece and the record stands today as a forgotten classic. Yet with the exception of a one-off single in 2000 and a retrospective box set, Beat Happening haven’t released anything else since. Officially on a kind of semi-permanent hiatus – though Johnson jokes they still practice every month – it’s hard not to wonder why the band went their separate ways at the height of their collective powers.

“At the time, in ’92, Bret needed to take a break from things for a while and that’s about when I started with other projects like Dub Narcotic Sound System and the Halo Benders thing,” says Johnson. “So I was doing other things and they were doing other things and we still are. I guess there was an idea of getting back together but it just never happened. People were getting on with other things.

“It wasn’t a conscious decision, you know? The conscious decision was, let’s take a break for a while. And then it just never really stopped. People have lives and things, they raise children, take pictures… Life can be so distracting. That can be your lead: ‘Life can be so distracting!’”