How a mythical Hollywood hotel inspired Jarvis Cocker’s and Chilly Gonzales’ project about the magic of cinema

Opening the door to 'Room 29', Jarvis Cocker discusses Hollywood, songs as social media and how to not go mad in a hotel room

Opening the door to 'Room 29', Jarvis Cocker discusses Hollywood, songs as social media and how to not go mad in a hotel room

Things happen at Chateau Marmont. Mythical, glamorous, sexy, seedy, wonderful, tragic things that befit the hotel’s location halfway along Sunset Blvd. They’ve written books about it, and Jarvis Cocker showed me two of his – The Chateau Marmont Hollywood Handbook and Life at the Marmont: The Inside Story of Hollywood’s Legendary Hotel of the Stars. The latter is a bit more gossipy, he tells me, although I imagine it’s a higher calibre of gossip that sashays through the lobby of Chateau Marmont. Fabulous gossip, surely; from a landmark of the Golden Age of cinema.

Resembling a Disney-fied version of the gothic Château d’Amboise it was modelled on (situated in the Loire Valley, France), the Marmont opened its doors first as an exclusive apartment building in 1929, as the arrival of sound in movies was revolutionising Hollywood. By 1931 it had been converted into a hotel, not necessarily with the express purpose of giving starlets and leading men a private environment in which to drink and shag themselves mad, but that’s how things went for the Chateau. It does, after all, seem ripe for abandon to this day, still boasting of “party-thick soundproofing walls” on its website, to “ensure privacy” for impromptu get-togethers that are seemingly encouraged by the hotel’s notoriously discreet staff.

Harry Cohn, the founding president of Columbia Pictures, famously once said: “If you must get in trouble, do it at the Chateau Marmont,” and countless stars have since obliged. Jim Morrison fell off the roof as he attempted to swing into his room; Britney Spears was banned for smearing food over her face in the restaurant amidst her sad breakdown of 2007; James Dean landed his role as Jim Stark in Rebel Without A Cause by jumping through a window to impress Director Nicholas Ray; the way in which Dennis Hopper would host orgies at the hotel was shameless in a way that doesn’t exist anymore.

Much of this doesn’t interest Jarvis Cocker so much as the Chateau’s origins at the birth of modern cinema. That’s what his new album with Canadian pianist Chilly Gonzales explores – the fantasy of film and the possibilities that come with checking in to any hotel. And for the real life Chateau Marmont guests that feature on ‘Room 29’, Cocker writes about Howard Hughes and Jean Harlow, leaving the more salacious inhabitants to their perpetual myths.

“Of course as soon as I said to anybody that we’re doing a song cycle about the Chateau Marmont, all they’d ask was, ‘Is John Belushi in it?’” he says mimicking a fevered, macabre whine. “‘Is room 29 where John Belushi died?’ I wanted to stay away from the Hello! magazine aspects of it.”

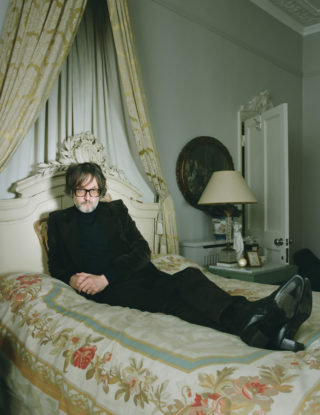

Keeping to the inspiration of the hotel, Jarvis sourced our meeting point himself; an opulent location house in north London called The French Rooms, which has been authentically filled with every antique imaginable from a grand house in 19th Century France – chairs, mirrors, chandeliers, candelabras, side tables, perfume bottles, birdcages and delicate, pale fabrics. Bar one small flat screen TV in the sitting room you can easily kid yourself that Versailles might be outside the front door you just walked through. It’s kinda surreal, and a little more so when Jarvis arrives, on account of how unmistakable a figure he has become. It’s not as if I was expecting him to turn up in a tracksuit talking like a market trader from Bow, but still I’m aware of how familiar his voice is, and how he’s matched brown corduroys with a black polo neck and blazer in that way he does.

Although greying, he looks young, or in good health, at least. He’s dry, of course, and sometimes indicates a joke with the slightest hint of a smile as he tells them. And when he poses for our photo shoot he’s even more like Jarvis Cocker when it didn’t seem possible.

Before he jumps on the antique bed and insists, “I won’t do any topless shots, alright?!” we take a seat on a feathery sofa in the room next door, where he shows me his two books on the hotel.

Of The Chateau Marmont Hollywood Handbook he says: “I don’t know why I bought that book at the time, but it made an impression on me, and it was a time when I wasn’t feeling so well.”

That was 20 years ago, when Jarvis picked up a tropical disease whilst on tour with Pulp. They dumped him at the Chateau and continued on to Colorado and The Rocky Mountains in an attempt to find another iconic hotel – The Stanley from Stephen King’s The Shining.

He’s been carrying the book around ever since, and when Pulp briefly reformed in 2011 he found himself back at the Marmont for the week between the band’s two performances at Coachella in 2012. With the hotel oversubscribed he was upgraded to room 29 – perhaps the only room with its own baby-grand piano. “And that was a light bulb type of moment,” he says. “As soon as I saw the piano in the room I rang up Gonzales very excited and said I think I’ve found the idea that we could do! Because I’d known him for a while and we’d bumped into each other and realised that we both lived in Paris. We’d worked a little bit together and we were thinking of doing a bigger project – we just didn’t know what.”

Jarvis’ inspired idea was to make a record of his voice and Gonzales’ sparse piano, inspired by the hotel and some of its classier guests, and in turn reflect the Golden Age of cinema and what it is to fantasise about living in a movie.

“With this, it’s basically saying, ‘that piano’s been there, what has it seen?’ Now it’s going to play you the songs that tell you the stories of what it’s witnessed.

“But it’s really a record about how films have affected human beings,” he says. “I’ve always been fascinated by that, because I realise they affected me a lot.”

Chilly Gonzales has since moved to Cologne. We spoke on the phone the week after I met with Jarvis. “Hi, it’s Gonzo!” he yelled down the line. “When he first told his idea to me, I thought, how perfect! You can just imagine Jarvis sitting in an opulent hotel room having a nervous breakdown, thinking about these things.

“He had a very clear idea of making it very personal while at the same time exploring the hotel. This is something I really liked because most people could have the idea to do a record about all the crazy things that happened in that hotel. Jarvis wanted to get past that salacious surface and get to a deeper understanding of what it is to watch a movie and fantasise about what it is to live inside it.”

“That’s nearly 5 years ago and we’ve been working on it ever since,” says Jarvis at The French Rooms. “Gonzales started sending me bits of music, and I started researching. I remembered this book immediately. I remembered that it was in the house somewhere and found it, and I started delving into the stories of it.”

The Hollywood Handbook confirmed that Jean Harlow had honeymooned in room 29, so Jarvis wrote ‘Bombshell’ – about the movie siren who also had an affair at Chateau Marmont with Clark Gable, and who died prematurely of kidney disease at the age of 26 as one of the biggest stars in the world.

The mythical aviation and movie pioneer Howard Hughes gets his own song, too, as the eccentric billionaire with such acute OCD that it would eventually lead to him refusing to leave a darkened screening room for 4 months, where he’d continually watch movies whilst eating chocolate bars and chicken, drinking only milk, and storing his own urine. He’d spend his time at Chateau Marmont in the penthouse, reportedly spying on the swimming pool through binoculars.

To call ‘Howard Hughes Under The Microscope’ a song, though, is misleading. It doesn’t feature Jarvis Cocker, or anyone else singing. Instead, Gonzales’ pretty piano is joined by ‘Room 29’’s third player – film historian David Thomson (“Not Daley Thompson,” smirks Jarvis). In 2014 Cocker and Thomson met at the Chateau; the croaky tapes of their conversations come and go throughout the album, like some ghostly lecture. And while we’re on the point, to call ‘Room 29’ an album is pretty misleading, too.

If both Jarvis and Gonzales impress one thing upon me it’s that ‘Room 29’ is not a musical. Jarvis tells me as much by saying: “I want to stress that it’s not a musical. And I also really want to stress that it’s not an opera.” Gonzales, who I enjoyed talking to for his exuberant manner, which, incidentally, isn’t unlike that of Gonzo from The Muppets, told me: “Musical theatre is made of cheese, and we would never go there!”

‘Room 29’ is their song cycle, in the traditional sense of the term. “It doesn’t have a story like a total narrative, but there is a logic to it,” says Jarvis, who points out that when they perform it at the Barbican later this month they’ll be doing so playing the tracks in the order of the record. In fact, says Jarvis, it’s the performance that is the project, complete with a stage set and projections of old movie clips and footage that the duo have themselves shot at Chateau Marmont.

“For a long time we wondered what this was going to be,” he says. “At first I thought maybe it would be a radio series, with a song at the end of each episode. Then I talked to a friend at Warp Films, Mark Herbert, and he said why don’t you make a film about it. So we went and filmed some stuff there. Eventually it’s ended up being a stage show, really. The thing that we’re doing at the Barbican, that’s the thing, really. The record is kind of a soundtrack album, in a way. Or the original cast album.” He laughs.

Gonzales later told me: “Jarvis called me and said, in dry ‘Cockerian’, if that’s an adjective, ‘I think we could be on the cusp of finding a new form of entertainment.’ Even in just trying to do that you end up outside of the usual idea of concerts and albums. So you end up with an album that kind of has a narrative but isn’t a piece of musical theatre – God forbid! It breaks you out of the album as a bunch of songs.”

Gonzales has been doing this his whole career, perhaps as the only artist in the world able to release rap and electronic records beside classical albums of minimalist piano inspired by Erik Satie. As a jazz virtuoso who began teaching himself to play at the age of three, he’s as comfortable collaborating with Peaches and Daft Punk as he is leading an orchestra in a concert hall or deconstructing the songs of Nicki Minaj and Taylor Swift for his Pop Music Masterclass lectures on YouTube. And when you’re that good, stepping on stage and playing a typical show isn’t so appealing.

He told me he considers himself an entertainer, first and foremost. I told him what Jarvis had said to me when were discussing the live show – “Gonzales can scare some people.”

“I like to play with audience’s expectations a lot,” he says in defence. “A concert is a predictable situation – I like to challenge that. I like the idea of transgressing and earning back the redemption. It involves trolling them in some way.”

At previous shows this has included Gonzales conducting a Pop Music Masterclass with the aid of a string section. They play a recognisable extract from ‘Eleanor Rigby’, after which Gonazles says to the audience, stony faced, “Of course you probably know that song – ‘Elizabeth Riddly’ by The Rolling Stones.” And that’s it. The masterclass continues and everyone has a lovely time, except for that awkward moment when the piano genius got the famous song wrong in front of 2,000 people. How embarrassing. The following day Gonzales gets his payoff when he checks his Facebook feed to find a host of comments from fans saying, ‘Great show last night maestro, but one small thing…’

It’s a brilliant gag, essentially because it’s for an audience of one – the teller. But it’s designed to affect the room ever so slightly – to shift the comfort of the predictable situation.

“That might be what Jarvis meant when he said that I scare people,” he says. “And what brings us together, other than our sense of humour and love of music, is, when you see Jarvis on stage or me on stage, you get the feeling that you’re witnessing us living out a fantasy. In a sense, to go on stage is to live in a movie, for me.”

“I have a thing in any hotel I stay in now where I try to unplug the TV and put it in a closet,” says Jarvis. “Or I just put a coat over it. I don’t like it. I feel like I watched so much TV as a kid that I’ve done my time; I don’t need to watch it anymore.”

‘Interlude 2 – 5 Hours A Day’ is another David Thomson track, featuring just two sentences from the historian: “The fact of the matter is, if you’re average, you probably grew up watching 5 hours a day. Now, I bet you didn’t spend 5 hours a day talking to your parents.” That was Jarvis Cocker, who, along with the other children of the late ’60s and early ’70s, gorged on the new medium of television.

When Jarvis’ father disappeared when he was seven, he says he started to look for clues on how to be a man from his beloved TV that puzzled and thrilled him.

“Which is a terrible place to look,” he notes. “I mean, I was never going to be a cowboy or a rugby player, was I?”

‘Interlude 2’ is then followed by a song called ‘Daddy, You’re Not Watching Me’, and early on in our conversation Jarvis pointed out that although Chateau Marmont is a place full of fanciful legends and fruitful inspiration, ‘Room 29’ needed to be personal to him, not just a bunch of stories about other people going wild on Sunset Strip. “There would’ve been no point making it a docu-drama,” he said.

He nods at the flat screen that’s out of place in this French period room. “Some people have trained themselves to ignore the TV in the room, but I can’t. Even the fact that that telly is there now is a little bit disturbing, but if it was on, our conversation would quickly grind to halt. Not because I’m not interested in you, but because, it’s like I’ve got a respect for moving images in some way, and it hypnotizes me. I hate when you go into a bar and there’s a telly because I’m sat there thinking, why am I looking at that – I’m not interested in… hockey. And that’s part of what I was talking to David Thomson about.

“What got me into him was he’d written this book called The Big Screen: The Movies and What They Did To Us. So he’s a good writer on the subject of how movies have affected human beings – it’s got into our DNA, in a way.”

He reflects on how moving image must have seemed like magic at the advent of the cine camera, and how we’ve become immune to pictures with movement in the modern age, as we trundle past them on tube elevators as easily as we look at them on our phones for fear of being under stimulated while the bus takes another 60 seconds to arrive. “It’s a shame, because it should still be exciting that you can capture reality. It’s almost as if moving image has replaced reality.”

Jarvis’ relatable fascination with film and television is only half of ‘Room 29’’s dreamland, though. Chateau Marmont is in the middle of Hollywood, and intrinsically linked to the magic of movies, but in its simple form it’s a hotel, and hotels come with their own fantasies, regardless of where they are.

Jarvis tells me: “When I was a kid, and maybe this is one of the roots of this record, I remember at the age of 8 or so, my ambition was to live in a hotel and be rich and have enough money to pay a servant to project my favourite television programs whenever I wanted, which at that point were The Monkees TV show and Batman. That was my ambition – you’re in a hotel so someone else will make the bed, I’ll just ring down for food and the tray will disappear afterwards. All that stuff. Embarrassingly enough, I think that ambition stayed with me for a long time.”

Until when, I ask.

“Probably until about a week ago.” He smiles and then laughs. “Of course, now I could do that. I can afford to check into hotels, and I wouldn’t need the servant, because in the interim Blu-Rays and DVDs and streaming were invented.

“I don’t know if I’m totally alone in that ambition. It’s that thing of not wanting to commit to anything, and just wanting to slide through life, without having to pick up your own mess or really get involved too much.

“You could say that part of this record is exploring that. Where did wanting to live like that come from when I was a kid?”

The thing about a hotel room is that it’s a blank page, he says. “I think that’s why people can lose it or break down in a hotel room. Because at some point you’re just faced with yourself.”

Jarvis pulls out his phone to read me a quote from British writer Geoff Dyer, which he wanted to use in ‘Room 29’ but didn’t manage to get clearance on in time. He swipes back and shows me some other research photos he’s taken – a Photoplay fan magazine from 1917, outlining a manifesto for Hollywood on how all films should have happy endings, and the stylish Do No Disturb door hang from the Marmont.

“Right. Here’s the quote,” he says.

“Hotels are synonymous with sex. Sex in a hotel is romantic, daring, unbridled, wild. Sex in a hotel is sexy. Even if you’ve been having a sexy time at home, you’ll have an even sexier time in a hotel. And it’s even more fun if there are two of you.”

Naturally, his reading of this is knockout, while ‘Room 29’’s opening title track has Jarvis loudly whispering the rather more blunt, “Is there anything sadder than a hotel room that hasn’t been fucked in?” It’s almost enough to distract you from the line in the chorus that starkly sets out the record’s true reflection: “Room 29 is where I’ll face myself alone.”

“I think as soon as you walk into a hotel, you’re already starting to come up with some fantasy of what you should be doing in the hotel. Especially if you’re living in a hotel like the Chateau Marmont, with all this back history. I think that can cause people to have episodes and issues, because it reflects back on you what you are.

“I am fine with hotels now,” he says when I ask. “I no longer have any episodes. I enjoy them for what they are. But especially with rock’n’roll things, there’s an idea that – not trashing the room, because I always thought that was stupid – but that you should be doing something newsworthy. You might just want to be tired and have a lie down.”

He tells me that the live show tackles the myth of rock’n’roll excess in hotel rooms, although he doesn’t tell me how for fear of ruining what he describes as “quite a big moment” in the performance. Perhaps it will be illustrated with the ridiculous story of John Bonham riding his Harley Davidson into the lobby of the Chateau Marmont – the biggest cock-swinging moment in ’70s rock history, which Led Zeppelin would repeat at the neighbouring Continental Hyatt Hotel (‘The Riot House’). And yet a story like that feels a little too low-rent from ‘Room 29’.

The vein of Jarvis Cocker writing songs about the spell that movies can cast upon us goes back at least as far at Pulp’s breakout 1994 album ‘His ‘n’ Hers’ and ‘Happy Endings’ – a song that dreamily builds to a widescreen crescendo having started with the line, “Well, imagine it’s a film and you’re the star.”

“We kiss to violins,” he sighs, as if to a black velvet backdrop punctured with light bulb stars on a soundstage in Burbank.

By 1997’s ‘This Is Hardcore’, the now famous Jarvis slipped behind a more sexualised silver screen of Bond villain brass and overt voyeurism, purring, “I’ve seen all the pictures / I’ve studied them forever / I wanna make a movie so let’s star in it together.”

‘Room 29’ goes for something less filmic and more intimate in tone. “Hopefully it feels like you’re sat in the room and the piano’s playing and I’m about a foot away from your face,” says Jarvis. “It should feel like it’s happening in front of you.”

That’s exactly how it feels. Jarvis’ deep voice and Gonzales’ dainty, dry piano – plus very little else on most of the record’s 16 tracks – make for a borderline claustrophobic listen, or “the feeling of containment,” as Gonzales more accurately put it.

It’s an atmosphere they created with a dogma filmmaking-like approach, laying out a set of rules and trying to stick to them. So Gonzales’ piano is largely without sustain pedal to blunt the sound and reduce the space, and Jarvis’ vocal is high in the mix and whispered into your ear. The one wide-screen moment purposefully comes at the end of the record, with ‘Trick Of Light’ (an ode to the wonder of cinema), where choral backing vocals and orchestrations signify that you’ve now entered the movie you’ve been dreaming of living in, or that you’re fully under the spell of the fantasy, at least.

When Gonzales started sending Jarvis some ideas to start work on, he did so in the way that he does when he works with Feist or Peaches or anyone else – Jarvis received short, rough demos; merely a starting point. After a while Gonzales realised that Jarvis was writing his lyrics to exactly what he was receiving, rather than feeding back with how they should repeat x bar twice, add a bridge, speed this up, slow that down – the way songs have always been written. It was a challenge that Jarvis had set himself, to force him into the odd structures that make up ‘Room 29’, and it accounts for the song lengths ranging from 1:16 to 7:23. He even wrote lyrics to some of Gonzales’ working titles, like ‘Tearjerker’ and the rather silly ‘Belle Boy’ – “a slightly more upbeat one so people don’t kill themselves halfway through the performance.”

Gonzales – a man who lives to deconstruct the workings of music – told me how Jarvis’ low, northern register allowed him to prettify his piano (it’s the other way around with Feist, he says, whose voice sores, and so needs to be paired with darker music), and he’s also keen to point out what a good job his friend did on this record, and how that could have only happened now.

“Jarvis’ radio show gave us a new Jarvis that we hadn’t seen,” he said in reference to Cocker’s BBC 6 Music show that he started in 2009. “‘Room 29’ would not have been possible without him doing his radio show and using his voice as an instrument in that way.”

He was also right when he said, “Jarvis has always walked that fine line between ridiculousness and depth.”

For those that are fans of Jarvis Cocker for his wit – and let’s face it, who isn’t – ‘Room 29’ delivers with songs about a serving Belle Boy who stumbles upon shagging guests (“Life could be a bed of roses / If it wasn´t filled with so many pricks”), the idea of losing your head – literally – over television (‘Salome’) and that old black comedy goldmine of self-loathing (‘Tearjerker’).

“I don’t like art that doesn’t have some element of humour in it,” says Jarvis. “I mean, I hate things to be laugh-out-loud funny. I hate slapstick and all that, but for me, in day-to-day life, a sense of humour, you have to have one. It’s a real essential to survive. So when I come across something when there’s no humour at all, it leaves me cold, a bit.

“You do run the risk of people thinking that it’s all a joke, and that used to drive me mad in the early days of Pulp. People were always saying, there’s so much irony in your songs. And I always thought there’s absolutely no irony at all. Because irony implies a distance, and if there’s one thing that’s been consistent in all the songs that I’ve written it’s that there’s no distance. Songs are my social media. They’re my way of communicating with people. It’s always been my way of dealing with what I’m thinking and what I think about life. And sometimes there’ll be a joke in there to make it all bearable.

“But what people find funny varies,” he adds. “This record is coming out on Deutsche Grammophon [the world’s oldest record label], so we’ve been talking to the people there in Berlin, and one guy there said to me: ‘I really like that ‘Clara’ song’ [about the daughter of Mark Twain, who stayed at Chateau Marmont and married a pianist who died, which is how the baby-grand piano appeared in room 29, in Jarvis’ mind]. ‘Very sad, though,’ he said. ‘Very, very sad.’ And yeah, it is a sad story, because it’s about a woman who loses her husband, and then their kid, who is the last of Mark Twain’s bloodline, is a hopeless, drug- and alcohol-addled guy who dies at 40, or something, but for me that song is funny, because I rhyme ‘melodic’ with ‘alcoholic’, and you can’t make that rhyme with a completely straight face. I was excited to find that rhyme, and I know it’s faintly ridiculous. It’s black humour, but that’s the kind I like. Slightly nasty humour.”

I ask Jarvis the impossible question of what would have happened if he’d been upgraded to any room other than room 29.

“It would have all been about jacuzzis,” he says.

Would this project exist without that upgrade?

“Probably not. We had been looking for something to work on, but I’m a bit of a believer that ideas happen when they’re ready to happen. I think that your subconscious does a lot more than you’re aware of. I guess that’s why it’s called your subconscious,” he smiles. “A lot of stuff is percolating away. Pulp songs dealt with some of this stuff. I’d had this book for 20 years. So it was ready, and that was the trigger. Room 29 is a place inside your head.”