Holly Herndon – AI is not going to kill us; it might make us more human

Herndon’s new album, made with the help of artificial intelligence and a human ensemble, calls for us to reconsider our relationship with technology and who’s running the show

Herndon’s new album, made with the help of artificial intelligence and a human ensemble, calls for us to reconsider our relationship with technology and who’s running the show

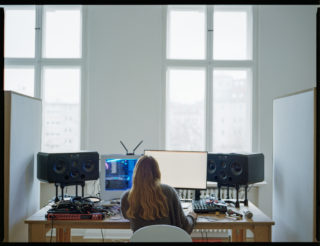

From the moment Holly Herndon opens the door of her west Berlin apartment I have one eye scanning the place for her baby. “What’s she doing right now?”, I ask when we find her sat at the back of Holly’s desk, partially obscured by a monitor. “She’s just chillin’,” says Holly, and we pass through into the next room.

When Holly is changing for our photo shoot, her PR and I go back and stare at the baby and agree how hypnotic she is. Her name is Spawn. She’s probably the height of any other baby out there but she’s square shaped and has a glass front, so you can see her heart beating in hues of pink, purple, blue and green. She’s an “AI baby”, which either makes everything I’ve said so far far less or far more creepy. That really depends on you, although, if you’re open to it, Holly and Spawn and the new album they’ve made together are capable of shifting your perspective on artificial intelligence and its place not just in music and art, but in our aggressively progressive world. To understand how we got to PROTO, though (out 10 May via 4AD), first we need to remind ourselves of how Holly Herndon became the only artist capable of delivering it.

For an electronic musician who makes music that’s as considered and complex as it is, Herndon’s influences are pleasingly simple to map out. “I’m definitely this weird combination of the idiosyncratic places I’ve found myself living in,” she says, referring to the three key cities of her life, which appear like a vapour trail across her music; the furthest away the faintest to detect. So let’s start there, in the Johnson City, east Tennessee: a hub for a rural and religious community, 50,000 people strong, with nothing to do.

As a kid Herndon would sing in church, play guitar and take piano lessons, and then grow bored of her small hometown. She’d go to a hardcore show when a friend would occasionally put one on, and a group of them would occupy themselves with ‘Food not bombs’ – a well-meaning soup kitchen drive, even if Johnson City had, like, one homeless guy, who was now fed for the entire year.

You have to burrow down through the abrasive electronics and processed vocals, but Herdon’s choir life and the folk music she grew up on are there in her thoroughly modern music, especially on new album PROTO, a record in which she overtly explores communal interaction. More apparent is the mark Johnson City has left on her personality. Photographs of Holly – our own included – paint a skewed picture of the woman herself, who smiles as easily as she bursts into laughter, and warmly welcomes us into her home. ‘Cold’, as electronic musicians and their music are often considered, couldn’t be a less appropriate word to describe her. And while every article about Holly Herndon inevitably descends into an academic paper suitable for a computer artist who this month will complete her PhD from Stanford University, she is neither as bookish nor condescending as jealous people like me so often project. It must be what they mean when they talk about Southern charm; supercharged, in Herndon’s case, by a desire to get out of there. So when she found out that her school offered one exchange program, to Germany, she thought, “obviously I’m going to study German then, because I want to get the fuck out of east Tennessee.

“It was so clear to me as a young person that I needed to expose myself to more,” she says, “and New York or L.A. wasn’t far enough. I wanted to forget that I was American for a minute. I didn’t want to speak English for a minute.”

I suggest how confident she must have been as a kid, traveling to Berlin for the first time at the age of 16, and then again for a whole year at 18.

“That’s an interesting word,” she says. “I was curiousabout the world I was getting glimpses of.”

She says she’d see Tori Amos on MTV, greasy and grinding on a piano, and think, “whoah! That’s emotive sexuality that I didn’t even know existed.”

Berlin instantly offered her what she was missing most in Tennessee: freedom. “I put on my hideous platform shoes and went down to the disco, and it was an amazing experience,” she says. She laughs as she recalls ordering Amaretto on the rocks, because a 16-year-old American in a German club (or in any bar anywhere) is as alien as experiences on earth come.

At the weekend, the family she was staying with would drive to the German/Polish border to buy cheap cigarettes and knock-off Adidas, where Herndon bought her first trance compilations. “That kind of music is so designed to tap straight into the mainline,” she says, tapping the veins in her arm. “Saccharine and synthetic, like, ‘this is amazing’.”

Berlin – spiritually when not geographically – hasn’t left her since. Even when she moved to Washington DC for college she used the tips she received in an upmarket steak restaurant to fly back to Berlin whenever she could, to meet her German boyfriend who she spent the entire summer raving with.

She describes the city’s club culture back then as “like going to church”, where everyone knew each other as minimal techno blew up thanks to DJs like Richie Hawtin and Ricardo Villalobos.

“I didn’t know the possibilities of electronic music until I came here,” she says. “I realised there was this whole other world.”

Berlin is the middle of the vapour trail and also its most recent and vivid part. Not just because Herndon lives here once again (with husband and collaborator Mat Dryhurt), but because the city’s electronic heritage has so clearly been the building blocks of her three albums so far. The obvious strains of techno that run through her music (as well as musique concrete: a composition tradition that often uses ‘non-musical’ recordings as source material – in Herndon’s case, how she recorded the sound of a dancer moving through space for part of her previous album, Platform) run alongside the third key city of her life and everything she studied in northern California’s Bay Area.

Berlin had made her fall in love with electronic music; Oakland’s prestigious Mills College gave her the tools to participate beyond the role of a spectator. Most importantly of all, it was the place where she chose her instrument, and realised that that’s exactly what a laptop can be. Her music has been intrinsically linked to her studies and computer technologies ever since, from her 2012 debut, Movement(which balanced the precise minimalism of her classes with the club throb she missed from Tresor and Berghain), to Platformin 2015

– an album that used tech to hold tech to account, as it criticised the manipulative nature of centralised social media platforms.

“I didn’t know that I gave a shit about electronic music until I moved here [to Berlin],” Herndon notes, “and I didn’t know I gave a shit about technology until I moved to Oakland. That’s the thing in life: you keep uncovering these things, like, ‘oh shit, that’s my jam!’ Who knows what that next thing’s going to be.”

Getting into Stanford, she says, “was a total surprise. A miracle. And it’s the next level when it comes to the technical level.” Which I guess is how she ended up here, with an AI baby in the next room, just chillin’.

Chances are your feelings about computer technologies range from the suspicious to the scared shitless. AI has always lived at the apocalyptic reaches of the scale; seemingly the natural end point of technology gone wrong being a robot that stops obeying its master and instead decides it wants us all dead. For added chill, Hollywood will give these disobedient killing machines human form so lifelike as to be undetectable in the street, plunging us into a world of absolute mistrust and perpetual fear. From Blade Runnerto Ex Machina, to Postman Pat: The Movie, we’ve repeatedly been told to distrust AI since at least 2001: A Space Odyssey’s murderous spacecraft pilot HAL 9000.

Herndon and Dryhurst firmly reject such kitsch ideas of a possible dystopia but agree that we should all be critical of technology and certainly those who control it. The tech threat they have always focused on is more real than HAL 9000, and already upon us.

When I ask Herndon if she ever feels scared by technology, she says: “Of course. We all are. With Platform, the whole album was about the power of these [social media] platforms, and how much they shape our lives, and a few years later Facebook swung the election. It’s not even a joyous thing like, ‘I told you so’, but at shows years ago we were like, ‘leave Facebook’. It wasn’t a surprise – this shit has been clear.

“The internet was the wild west; now it a mall,” she says. “That wasn’t the cyberpunk dream. And then you see Congress trying to grill Mark Zuckerberg and they’re asking him how their iPhones works. That’s a different company! You’re not going to be able to take care of it.”

The use of Spawn on PROTOis likely to lead some to be instantly dismissive of it. After all, the big headline of the record is ‘Holly Herndon’s made an album with AI’, which is not just open to oversimplification but false assumption too. That assumption is essentially this: Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst built an AI machine and called it Spawn, which then did all the work for them and spat out this record of weird, twisted electronics – as if it wasn’t bad enough that she already makes all her music on a laptop. For some, the fear of AI here is even greater than a killer-bot uprising; it’s taking away our precious music: the purest expression of mankind; the closest thing we have to magic, no more legitimate than when wire strings are stretched across wood and pressed with real life fingers.

It’s a little woolly, but I get it… although it’s not true in this case. Because while PROTOwas created using elements of AI, Herndon and Dryhurst weren’t interested in automation (that assumption comes from a narrow view of what AI can be used for). In fact, if manual labour is a currency of authenticity in music, PROTOis more legitimate than most guitar records I can think of. As Herndon explains to me exactly how Spawn works, she notes that Spawn is only one member of an ensemble of 14 that includes Dryhurst and developer Jules LaPlace. The remaining members of the group are vocalists who would meet to “feed” Spawn by singing and talking to her.

Perhaps it’s worth us defining what an AI (or, to be more accurate, ‘machine learning’) is before we go any further: broadly speaking, it’s a machine that receives information and from that interaction gains some more information that it can then do something with. The original information you feed into your AI is called a data set, and usually comes from an open source online. But Holly wrote her own data sets, which she then taught to her ensemble who then read and sang them to Spawn in an attempt to teach her to not just repeat what she heard, but to learn more of the language from. PROTO’s purest example of this is a collaboration with footwork producer Jlin called ‘Godmother’ – a wilfully ugly sounding track of stutters and hisses. When I inevitably ask Herndon if she feels affection for her AI baby, she says she felt it most on ‘Godmother’, when Spawn started to sing in her voice, where it sounds like she’s beat-boxing like Timberland. “And believe me, I have neverbeat-boxed,” she cries. “I was horrified when I heard it. But it was also hilarious, because it’s the mix of singing and speech and her trying to make sense of that.”

Typically, PROTOwas made thus: once Dryhurst had put Spawn together in a gaming PC, and LaPlace had begun developing her without learning parameters, Herndon and her group of vocalists would sing and read to her for hours (including one public training performance of 300 people, to teach Spawn how to create music from a large gathering of voices). For two years this went on, originally delivering mostly noise, until one day, after 6 months, “we thought, finally, something that doesn’t sound like shit. Which is why a lot of people aren’t fucking with AI,” says Herndon, “because it’s annoying, and there was the first 6 months when everything sounded like ass.”

The project’s breakthrough moment features as PROTO’s opening track, ‘Birth’ – a holy tone over which Spawn garbles to life in Herndon’s voice. “That was when we were first really excited,” she says. “There were words in there that I wasn’t even saying. Like, she says ‘cunt’. Kids say the darndest things,” she laughs.

Where ‘Birth’ is minimal and only 75 seconds long, the rest of PROTO’s production could only just begin. Using the tradition of musique concrete,think of it this way – Holly Herndon could have sourced a bunch of sound as material from anywhere within an hour and then started to make her third album with it, beginning the process of tirelessly iterating and drawing on her own compositional skills to add her own elements. There would have still been months of work ahead of her to create a record as emotive and unique in sound as PROTOis. Instead of that, she spent two years generating her source material by educating herself in AI and training an AI baby with a community of people that at one point totalled 300 at Berlin exhibition hall Martin-Groupius-Bau. “So it’s not about automating the composition process or trying to replace that at all,” Herndon stresses. “It’s about trying to find what’s aesthetically interesting and new with this new technology which can be used in a compositional environment.”

She points out that most AI experiments in music have gone down a far simpler route of imitation of composition, rather than using sound as material. So a study teaches an AI how Bach would use notes (their pitch, length and rhythm) and set the parameters for the machine to learn from that and create their own Bach-like pieces of music. “For me, that’s really not interesting,” says Herndon. “That leads to this retromania and repetition of itself. We were much more interested in sound as material. And it’s more personal because you’re training it on a person and their sound.

“Putting the ensemble together was part of the broader PROTOapproach,” she goes on. “We saw how fully automated electronic music was becoming – and of course I’ve been part of that: drum machines, computer music etc. – and we wondered where that can go and where the human fits into live performance, especially within these super synchronised AV hybrid DJ sets. We were questioning where do humans fit into this. What things are worth preserving and what things are worth automating? To do that I wanted to work with humans, still working with the computer as the brain. And so that’s why we started the PROTO ensemble. And we saw Spawn as part of the ensemble, and Jules [LaPlace]. Part of that was having them over and us singing together, which I’d record, and a lot of that I’d train Spawn on. Then I’d cook for everyone, which sounds really hippy.”

Having taken German at school solely to “get the fuck out of east Tennessee”, these elements of a record that seems so technologically advanced are rooted in Herndon’s earthy upbringing, from singing in choirs to making soup for others. After two albums of little face-to-face interaction (Movementwas very much a solo album, while the collaborators on Platformwere largely reached online) Herndon missed people. She says: “One of the reasons I wanted to do it was because I was really lonely in the studio. Of course there is still a lot of that – after the recordings someone has to sit there and listen to every single take for hours – but that human contact was a huge part of it.”

So rather than PROTObeing a symbol (and warning sign) of how humans could even be made obsolete within making music, it’s quite the opposite – Herndon is using tech to get more human interaction into her life.

“That’s the whole point,” she says, “technology should free us up to be more human. That’s what it should be doing, so we don’t have to go through these machine-like motions. The human body has been like a machine since industrialisation, so how can technology get the body out of these machine-like motions so we can be more human together. That’s the vision.”

It brings to mind Herndon’s views on collecting vinyl – something she doesn’t do, much to the horror of some. But her argument in her defence is not just pragmatic but honourably egalitarian as it sticks up for modern technology. Put simply, digital music has made music instantly accessible in every corner of the world, more regardless of wealth and class than ever before. Even in terms of sharing music with a friend, they don’t need to come over to pick up your LP anymore. Should that convenience not be celebrated? Is that not an example of technology freeing us up to be more human?

The resulting album is not always the most comfortable listen, although Herndon’s music never was, even before she started fucking with AI. Still, when you consider how it was made, it’s something of a miracle how ‘musical’ so much of it is, while on tracks like ‘Eternal’ and ‘Alienation’ Herndon is the most human and accessible she’s ever been.

PROTOwas a bold new experiment, and it plays out like one, with all elements of Herndon in there. After her baby gibbers to life on ‘Birth’, ‘Alienation’ is one big down-tempo build of dark ambience and Enya-like, semi-decipherable vocals. It takes no time for it to reach euphoria.

Other digestible moments come in the dreamier ‘SWIM’ and ‘Last Gasp’, which grooves not unlike Massive Attack to close the album in a melancholic and human way after all the science that’s gone before it. ‘Fear, Uncertainty, Doubt’ is more machine than man, yet is perhaps the album’s prettiest track: a flutter of ascending robo voices. ‘Bridge’ is a disturbing boot-up accompanied by ghosts speaking nonsense, and ‘Godmother’, as I say, is wilfully ugly and best not listened to with the lights off. The remaining five tracks are where the PROTOensemble really fly, especially on ‘Frontier’, where the group vocals are goblin-fied and sound like early Yeasayer, and live training track ‘Evening Shades’: presumably the result of the 300-person learning exercise, it sounds like a hymn at a rugby match with a sound delay that makes everyone slur a little drunkenly.

Trying to work out what voices have come from Spawn, Herndon or elsewhere is practically impossible, which is kind of the point.

Late into the day I ask Holly what she hopes people get from this record. It’s the only question she pauses at before answering. “I want people to feel like they have a sense of agency in their lives, and I feel like right now people don’t have that. It feels like these insurmountable titans are controlling our lives, so by having this DIY intervention into something that feels monolithic feels like having a little bit of a say about it. And hopefully some ecstasy as well. I wanted it to be ecstatic, and it’s a communal record; a record of people in space enjoying being together.

“I’m not a religious person,” she says, “but I grew up in religious ecstasy, and this feeling of public ecstasy is something that I feel music can provide that a lot of other fields can’t.

“I think it’s really easy for us to think of ourselves as a kind of other, separated from technology, just like we do from nature,” she says. “We think we’re outside of it, but we are part of nature, and through our nature technology is something that’s come out of us.”

We do appear to be rapidly building technology while simultaneously rejecting it, and washing our hands of any responsibility. Which is why the common AI narrative is a dystopian one about machines rising up and wiping us out, seemingly without anyone thinking to say, “why don’t we just not build them, then?”.

It extends to our pessimism towards technology as a whole. We’re quick to deride advances as “too far” (driverless cars) or elitist and not for us (Oculus Rift), rarely considering the daily benefits of boring things like parking apps, emails and, simpler still, traffic light systems. Technology is Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, and who wants to be like those guys. It’s surveillance and infringements on our freedom. It’s a trap. Of course, we’ve been given good reason to feel like this, but with a shift of perspective and some plain optimism Herndon believes it can be different.

“One of the things about being the Bay Area was that there was a lot of DIY technology,” she says, “and that gives you a very different feeling than when you’re thinking of technology as this hyper capitalist American monolith that’s controlling your daily life and surveying your every move and trying to sell you shit. That is technology for a lot of people, because it’s how it’s applied in a lot of our lives. But it doesn’t have to be like that.

“Especially in electronic music it’s so cool to be dystopian and revel in the fucked-up-ness of it all. And I’m not a utopian but I think we have to be able to have a vision of what this can be other than that if we’re going to have any demands. Otherwise we’ve already given up. This project is trying to break it up. And there’s tonnes of melancholy on this album as well – frustration and being lost and sad, and mourning. But there’s also has to be, like, what do we want it to be then? If we don’t want this, what do we want it to be? And we need to get our hands dirty.”