Hen Ogledd – Four sentient blobs go on an experimental pop adventure

Turning weird psychedelic explorations into well-formed wonky pop songs

Turning weird psychedelic explorations into well-formed wonky pop songs

“You’ve got to admit there’s something about ABBA,” says Sally Pilkington in between bites of her toast and jam. “I wouldn’t say I was a serious fan or anything like that, but I’ve always thought they had this weirdness and darkness in their spirit; the way they often buried the sadness underneath layers of joy.”

The reason I’m talking to a group of bearded, laid-back looking folk musicians about Sweden’s premier besequined pop legends is that Hen Ogledd name drop ABBA a lot. Not only are there mentioned littered throughout the promotional literature for their new record Free Humans, some of the album was even recorded in Atlantis Studio – the very same studio that brought us ABBA’s debut. At first glance, it might just seem like a bunch of musicians being deliberately obtuse, but when you stop and really think about it, you realise that both acts are actually kindred spirits. Just as ABBA’s sound took pop melodies and propelled them into weird, celestial places using a combination of disco and Bach, Hen Ogledd are doing the same thing. Except with more hedgerow electronica and lo-fi psychedelia.

For singer Richard Dawson, there’s another, more profound reason for the band’s ABBA worship, who’s name is, in fact, a kind of meta-commentary on the whole concept behind Hen Ogledd’s new album, Free Humans. “It felt right mentioning them because their name is also a palindrome,” he says. “It’s really apt for this album as there’s a lot of time shifts on this record. I mean, we start with the last song for one thing.”

The faces that make up the core of Hen Ogledd are no strangers to most Loud And Quiet readers. Beginning in 2013 as the pairing of Dawson and harp-touting sound artist Rhodri Davies – both successful musicians in their own right – initially the group was more of a jam band than a fully-formed musical project. Over the years, they have grown by adding fellow multi-instrumentalists Sally Pilkington and Dawn Bothwell alongside a couple of other on-and-off collaborators. By the time 2018 rolled around, they had morphed into a democratic arts collective, dialling down the improv and concentrating more on a community-orientated approach to songwriting.

“I almost don’t want to dwell too much on the beginnings of the band as I don’t think we really clicked without Dawn and Sally,” Dawson tells me when I ask about the early days. “We started pretty much as soon as Rhodri moved to Newcastle, but the music we made back then was really, really bad. A few years later Rhodri played on my Glass Trunk album. That was really going to be it until Lee Etherington of Tusk Festival suggested that we played a gig as part of his festival, and that’s when Dawn joined us. It’s been all down hill from there, basically.”

Alongside Dawson’s traditional folk back catalogue, the name Hen Ogledd (a Brythonic term for ‘The Old North’, referring to an area that roughly matches up to modern Cumbria and Northumberland), suggests that this band would have a rootsy sound. In fact, that couldn’t be further from the truth. If you manage to hunt down the band’s first couple of recordings, the solemn Dawson-Davies and the live album Bronze, you’ll find a free-form improv noise act that is closer to Amon Duul than it is to Pentangle. It made the band’s sharp left turn on 2018’s Mogic all the more surprising. Like a mist rolling back to reveal a figure beneath, the band kept the experimental blend of playful electronics and woodland folktronica, but gave the songs more structure and shape, effectively turning weird psychedelic explorations into well-formed wonky pop songs.

“I think the change came because suddenly we were all coming from very different places, but each had an area of crossover,” explains Dawson, showing how the evolution in style is really just the product of new perspectives. “For me and Rhodri we’ve always connected over a lot of Sun Ra, but adding Sally and Dawn brought a lot of different viewpoints. It takes me some time to get around it all. A lot of the time I might be going, ‘wow, that’s a bit of a strange angle,’ but then, that’s what makes it so great.”

Hen Ogledd’s move to the poppier end of the spectrum could be considered more of an evolution than a revolution. Even though the new direction has resulted in brilliantly meandering pop songs, the band go out of their way to stress that they remain improvisers at heart. However, the puzzle lies in how they actually make it work. How can four people who are all fiercely independent and prodigiously creative actually get together and combine all these visions without someone’s view eventually taking over? Our Zoom call suddenly falls ominously silent and some nervous glances are exchanged before Dawson starts to grin. “Y’know what,” he says, “I’ve been wondering the same thing too. It’s not really something that you can easily explain.”

“It’s hard because there’s really not any formula to how we come up with songs,” says Pilkington, beginning to flesh out the group’s answer. “Everyone is quite different in their approach. Some might be like ten per cent there when we start working on them, and others might be closer to ninety per cent of the way there, but they all take different ways to be finished.”

“I’m not sure if I really agree with this idea of completeness,” says Davies. “I’m not sure we ever end up finishing a song. To me, that feels a bit too like there’s a formula behind it. I feel that if you get too caught up with figuring out a method, you tend to end up getting a little bit stuck. So it’s good to make sure your footing is unsure a little bit. Maybe cooking is a better analogy, only because we all bring our own ingredients to the mix. Some people might bring more significant sort of carbohydrates. Others might be really incredible saffron, you know – stuff that will alter the flavour.”

“In that case, I generally just do the washing up,” deadpans Dawson.

In line with everyone else on the planet, 2020 has been a strange year for the members of Hen Ogledd. The last time the band managed to see one another was back in February when they played their one and only gig of the year, to a crowd of children at MAPS Festival. Somehow though, not only have they manage to move from Weird World Records to its big brother label, Domino, they’ve also put out Free Humans; a glorious, ambitious follow up to Mogic. It’s a record that not only builds on the wild inventiveness of its predecessor but also takes itself into some very weird sonic territory. I mean, to illustrate the point, as well as the ABBA references, the press release comes across more like a university reading list than a pop promo: influences cited include the twelfth century mystic composer Hildegard von Bingen, avant-garde filmmaker Werner Herzog and PC Music star Hannah Diamond.

Initially, Bothwell lets out a comically long sigh when I ask her about the themes on the new album. “Oh, god. It’s as confusing a question to answer as to how these songs came about in the first place. I guess we were all thinking quite disparate things at the time of writing the album and we sort of ended up smashing them together when we met up. It’s like we had all these seeds of ideas and just went, ‘let’s see what characters we can create with this.’”

“This was a strange album, really,” agrees Pilkington. “I think maybe it was because we all brought songs to this album that were kind of semi-written, so it feels more of a random mix of ideas than Mogic. Not that it’s a bad thing – instead this feels more like a whole ecosystem of things I love. Like sewers. And plant life.”

“At the time, I think the school strikes and the kind of environmental concerns were at the forefront of our minds, as they were for so many people,” adds Dawson. “So I think that played a big part in the record, but at the same time, and I don’t want to speak for the others, I didn’t want to make a polemic record. Right now though, it just feels kind of apt. The original idea was to get people thinking about our place on this planet as part of our ecosystem, but this led me down another rabbit hole. I started thinking about what kind of environments might exist on other planets, and then on to the idea of space travel, and then on to time travel. The whole thing was kind of a slippery slope.”

“I was also keen to rethink things and offer new possibilities of how things can be done,” says Davies. “I wanted to look at different ways of doing things and look at old technology with fresh eyes. You have these unfashionable things, like, say, the vocoder, which actually has this incredible history. I mean, it’s been ridiculed for years, but did you know the original one was first demonstrated in 1939? At the time it was this incredible, futuristic thing and yet now everyone’s laughing at it. In some way it was almost funny to include these artefacts from a future we never had.”

Even though its filled with moments of psychedelic hyperspace and flights of fantasy, Free Humans somehow feels like Hen Ogledd’s most earthbound album yet. It includes Welsh ghost stories and ancient, nine-foot-tall marsh monsters, and the use of Lee Patterson’s field recordings of sphagnum bogs to create an album that feels very much rooted to the land. With its bizarre energy and darker undertones, it could almost be a portrait of these isles themselves; inhabited by a people who are with one hand reaching out to an unknown technological future, and yet are stuck in a rose-tinted past.

“I think quite a few of the songs deal with our relationship with space,” explains Bothwell when I ask her about the record’s more rural feel. “I think it’s really a record that speaks about the land in terms of collective experience rather than who owns what. A good example is ‘Skinny Dippers’, which Sally wrote about skinny dipping in the North Sea, and how it was this brilliant collective experience. I think it flirts with the idea that you can’t really claim a place. Spaces are where people collect, connect and do things together and create these positive experiences. I guess that’s an essential part of making music as well. It’s as much of a collective experience as it is an individual one.”

“I think it’s also something that comes across by just looking about the span of time that we deal with,” says Pilkington. “Y’know, the way we look way back into history and then imagine futures out in space. I think it’s a perspective that only really zooms in on the ridiculousness of our present. If you take the long view, a lot of the things we quarrel about are all so pointless. I honestly think people will look back at on this era and wonder how we just let it all happen.”

“I’ve always been kind of puzzled by the idea that we are the centre of the universe,” adds Dawson after a little more thought. “It’s like somehow it arranged it’s molecules to create these sentient blobs who are all walking around struggling to figure out why they’ve been arranged in these blobs. To see ourselves as separate to that is not necessarily mystic, but it’s also only looking at half the picture. We are all individuals, but we also belong to a collective. We’re all basically walking contradictions.”

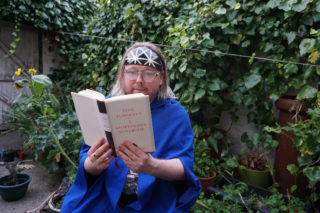

Photos by Math Roberts and band