Five days in Japan with Gold Panda

Shopping for tat in the country that inspired Derwin Panda's latest album, and discussing whether he’ll ever make another one.

Shopping for tat in the country that inspired Derwin Panda's latest album, and discussing whether he’ll ever make another one.

It’s midnight on Sunday in Kyoto when Gold Panda, dressed as a corn dog and with an easy flow, raps ‘Juicy’ by Biggie Smalls. Although he’d never admit it, he’s nailing it. Even the Total hook is sung in tune by the London-born, Essex-raised musician who grew up obsessed with hip-hop and fleeting rapped as RUM?ELST!LSK!N, Olivia Neutron Bomb and Kiss Akabusi. Clearly, Derwin wasn’t a teenager that took himself all that seriously, but the fact remains that tonight he sounds good.

As Japan’s thousand-year capital quietly prepares itself for another working week, he continues to sound good, too, as he croons Sinatra’s ‘That’s Life’, mock rocks ‘Don’t Stop Believing’ and duets on ‘Hollaback Girl’ with friend Miho. I murder my halves of ‘Faith’, ‘Common People’ and, devastatingly for me, ‘Panic’, but Derwin is a karaoke king, dressed as a corn dog… sometimes a sailor. Why can’t all cover features be like this?

In 1999, at the age of 19, Gold Panda flew to Tokyo for the first time in his life. By all accounts he felt prepared, having video recorded a bunch of documentaries on Japan over the preceding years, and having taught himself the basics of the language with a BBC tape pack. He arrived in August in 90% humidity to a storm of massive flying bugs that gave the city an extra dose of alien that it really doesn’t need. “Even going to the supermarket was exciting,” he remembers, which might explain his continual love for the Seven Elevens and Family Mart convenience stores that are never more than an irregular block away.

For two weeks he stayed with his friend Phil Wells – from Techno group Subhead – and techno DJ Mayuri, followed them to the Maniac Love club in Omotesando, Shibuya, and a love affair wasn’t so much born as cemented. Derwin was sure that he’d get on with Japan – how couldn’t he; they liked all the same things – Street Fighter, animation, arcade games, hip hop, house and techno. He flew back two years later for six months of the same, renting a room once more from Phil and Mayuri, working a little as a teacher – but not much – and getting hammered. “Oh well,” he says. “Maybe it was better that way.”

By October 2016, now aged 36, he’s lost count of how many times he’s flown to Tokyo. Japan has become part of him. He’s fluent in the language, has a wealth of friends here – including some that he met on his very first trip in ’99 – and his latest, third album, ‘Good Luck And Do Your Best’, was directly inspired by a 2015 visit with his girlfriend – photographer Laura Lewis. Together they’ve just released a book of Laura’s photographs from that time; the field recordings that were supposed to act as its soundtrack ended up becoming ‘Good Luck And Do You’re Best’.

As guides to Japan go, then, and having never been myself, Derwin is the perfect host, who I’ve gotten to know since the release of his debut album, ‘Lucky Shiner’, the ambient techno sleeper hit of 2010. Over five days we’ll travel from Osaka to Kyoto to Tokyo, for three shows – perhaps the last he’ll ever play here as Gold Panda.

When we meet in the lobby of our hotel in Osaka at 6pm I’ve had two hours sleep and Derwin, a self confessed lightweight, is severely hung over. Last night he arrived in Tokyo and uncharacteristically stayed up late and got wrecked with friends he hadn’t seen for a while. The centre of Osaka – a short metro journey away – is what both of us need, and probably Dan Tombs, too, although Derwin’s soul tour mate and live visuals coordinator (Dan is also responsible for the screen displays of Jon Hopkins, Factory Floor and The Charlatans) looks pretty fresh.

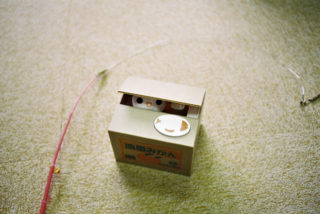

Since returning to London, I’ve realised that attempting to describe Japan is almost as futile as enthusiastically retelling the dream you had last night – “You were there, but your arm was a bubble, but I didn’t find that weird, and then we were in a park, but the floor was made of egg… but different egg…” Many elements of Japan are like that. The trinkits and souvenirs are wonderfully abstract, from the recurring white cat with a piece of sushi on its head, to the ¥200 gashapon vending machines that dispense every baffling thing from miniature figurines of dogs in baked goods to tiny coloured wheelbarrows and hardhats. One of them spits out a series of 2cm long toilet rolls and accompanying holders. It’s all cute cute cute and so intoxicating that before long you find yourself almost buying a bottle of Domestos because it’s got a picture of a bear’s face on it. Every other street either illuminates like Times Square or is a single-file passageway lined with restaurants for a maximum of 10 diners. In the middle of Osaka, quite unexpectedly, there’s a straight river where a road should be, on which a brass band sails up and down playing New Orleans dixie jazz, past an oval version of the London eye wrapped around a you-can-literally-buy-anything-in-here store called Don Quixote. The floor is not made of egg, but you can see what I mean.

For the next five days, Derwin, Dan and I will spend our time buying the most bizarre tat we can actively find (crisp key rings, bullet train shaped staplers) and sampling Japanese food not available in Tesco (puffer fish, sea urchin sushi). There will then be a brief interruption while Derwin plays a show to a dark room of bubbling bodies that negate the myth of Japanese audiences being completely static at gigs, which I’m looking forward to the most, and Derwin most certainly isn’t. “I don’t think people really like my music here,” he says when I ask him what I should expect at Club Circus tomorrow.

If you’ve read any of our previous interviews with Gold Panda, you’ve probably picked up on how self-deprecating Derwin can be. And funny. And dry. When he says things like that, it’s not false modesty, but he is wrong.

Club Circus is a black box on the first floor. It’s hardly cavernous, but it’s close to its capacity of 200 when we arrive. “This is alright,” says Derwin as we enter. “This is all I want. I don’t want to be playing stadiums, because then your know your music is shit.”

Each of the three shows on this mini tour outdo the one before, but it’s in Osaka where I notice how much the room is moving, and how Derwin has equalised his 8-year catalogue to a level marked ‘club’. Mid-set high point ‘Clarke’s Dream’ has always been classic house faire, its horns and groove sounding like a set opener for Larry Lavan in 1980s New York, and ‘Vanilla Minus’ continues to dare you not to hook into its jabby techno pulse, but even new songs like the mellow two-step of ‘Halyards’ kick harder in between. When a guest on our podcast earlier this year, Derwin said that he didn’t consider what he does ‘club music’ and I agreed – now I’m not so sure.

“I have made the songs more banging,” he says when I mention all this to him. “Because I want to have fun. It’s getting closer to club music, and I listen to club music, I just don’t listen to it in clubs.

“I don’t really have any experience of clubbing, in the way that Detroit DJs would. I don’t find them to be the type of places I want to be in. It’s sold as this free environment where everyone’s friends and on the same level – I’m not convinced by that, but I like to think that that’s how a club night I’m not going to is going to be. I’m hoping that everyone’s there together and there’s great house tunes on, and they’re soulful, and there’s a positive vibe, and no one’s looking at each other because no one cares. That’s why Berghain’s good. That does have that vibe. Some weird shit goes on there, but that’s how a club should be, I think, where people are just wanking.”

Derwin, having lived in Berlin for three years while he recorded his second album, ‘Half Of Where You Live’, played the infamous Berlin club Berghain last week. He says he had a great time, although he almost blew out his ears due to his monitor being too loud. When he returned to London he was concerned enough to visit a hearing specialist in Harley Street. “And the guy there said that he’d seen my name come up and said that he’d do this one because he’s a fan of my music.” I can imagine how embarrassed Derwin would have been by that, while in Osaka, once his set is over, there’s a queue of fans waiting to meet him for photos and autographs. He signs not one but two iPhones. This post-show ritual happens again in Kyoto and Tokyo, which I take to demonstrate how enthusiastic and genuine the Japanese people are, and how much Derwin underestimates his appeal and what his music means to some listeners. When I ask him if he ever allows himself to enjoy those moments enough to take stock of everything he’s achieved as Gold Panda, I should have known that he’d say, “No way. I feel like I’m learning on the job.”

The following day we take the still futuristic bullet train (The Shinkansen) to Kyoto in 20 minutes flat. Rather offensively, it arrives on time, like everything else here, although I’m still marvelling at the fact that Japanese ticket machines can read multiple tickets when all inserted at once, rather than regurgitating just one because it’s slightly bent, or, of course, not bent enough. Not for the last time I am left wondering why Britain seems to have bought all of its computerised machinery from an end-of-the-line factory outlet store. The Shinkansen, meanwhile, has been operating since 1964 and is still around 100 years from our wildest dreams. God help us, HS2.

The donut shop in Kyoto station identifies your chosen filling via an infrared scanner, while the escalators at one end stretch up to the outside roof of a neighbouring, 11-storey department store. Halfway up, a stage us been built for today, where a school brass band are playing the theme tune of Super Mario.

Away from the station, Japan’s former Imperial Capital is a much more traditional city, full of beautiful temples and parks. Finding a bin anywhere is easier said than done, yet it’s one of the cleanest places I’ve ever been to – littering is no more done than crossing the road before the green signal, even if there isn’t a car in sight. It makes you check yourself if you’re hurrying, and again I can see why Derwin loves this place and continues to visit around twice a year.

Yet visiting Japan for fun and visiting Japan as a touring musician are two very different experiences. Or at least they are for Derwin – the country he loves being facilitated by the thing he loathes to do.

Derwin has always struggled with selling his wares on tour, regardless of how good he is at it. His shows are dedicated parties for fans of smart electronic music, and he’s a natural at meeting people – it just makes him feel uncomfortable and anxious. The worry now is of the country that’s always been his escape becoming entrenched in work.

“It hasn’t ruined Japan for me yet,” he tells me, “because I try to keep it separate. Most people would jump at the chance to play Japan at any time, but I’ve turned down gigs here this year, because I like it too much. Now I’m stressed out and I’ve got to do gigs, and I’m stressed because of what people might think. I’ve got to do interviews and speak in Japanese and impress people, which is not fun.

“When I arrived this time I was the most depressed I’ve ever been being in Japan. Like, ‘this is the worst, I don’t want to be here, I’ve got to do gigs.’” It was the first thing he said to me when we met in the lobby in Osaka, too, not long before saying it was a shame that I couldn’t have visits with him when he didn’t have any shows on.

In that sense, Derwin is like a touring musician inverted. We’ve all heard about how the road has driven artists mad, but the set narrative is about all that waiting around for one hour of pure, unbridled joy and purpose. For Derwin the opposite is true – the 23 hours of not playing a show can easily be filled with adventures in a place like Japan; the stress of having to disrupt that peace and excitement for a show in the evening becomes more and more impeding as a tour roles on.

Although he was on the road longer with ‘Lucky Shiner’ and ‘Half Of Where You Live’ (his decision to move to Berlin for the latter record was partly informed by Germany’s geographical proximity to other European cities for booked shows) Derwin’s done his fair share for ‘Good Luck And Do Your Best’ with the end in sight, which is of course when the end feels further away than ever.

“The problem with live gigs is that I always feel like I’m ripping people off,” he says, “because I’m just playing the same thing every time with a slight variation. There’s a thing with electronic music, like, how do you do it? Some people just turn up with a laptop [Derwin doesn’t], and people go wild while they’re not really doing anything. And I wonder if anyone really cares? Am I worrying too much?

“But I never get to see my own show,” he says. “I can only think what it must be like, and I think, ‘gosh, I wouldn’t want to be there.’”

When I ask why not, he says: “I think I’m not a fan of live music. I’ve always liked being at home and making stuff. Listening to records, cup of tea, Jaffa Cakes – that’s more me. I’d like a music room that’s just records, books… I want one of those John Lewis snug chairs – like a tiny sofa but a massive armchair – and a nice blanket and a lamp and a table.” No wonder Derwin didn’t get on with the nocturnal Berlin, although when Four Tet is going on at 6am, he reasons, you can get a good night’s sleep before heading to the club.

Needless to say, Derwin is almost ecstatic when he finds out that all three of the shows on this tour have early stage times of 8:30pm, tonight’s being at Metro Club – a boiler room in a subway station that’s got a good feeling about it.

Again the room jumps and vibrates. Again ‘You’ gets the cheer it always will, but again the reception for new track ‘Time Eater’ – ‘Good Luck…’’s and Gold Panda’s most outwardly Japanese-sound track, all spidery ’80s goth plucking and skittish drums – beats it.

For an artist who adamantly doesn’t do encores, Derwin’s hand is forced tonight when he’s trapped between the small stage and exit with the realisation that people aren’t going to leave. It’s an awkward, British, Derwin 5 minutes as we all wait for Gold Panda’s equipment to reboot for ‘You Pt. 2’. When he jokes that someone could buy him a gin and tonic while we wait, a number of people fall over themselves to be the first to the bar. Surely he can’t really think that people in Japan don’t really like his music.

“I do genuinely think that,” he says. “Maybe some people like me because I like Japan. But most people don’t want Japan again. They want the Rolling Stones or Orbital or Oasis.

“When I was first here western music was huge, and now it’s kind of gone. Now it’s all J-pop and J-rock and J-rap. They’ve got their own stuff that’s come through and it’s outselling the western music. We really think we’re the best, but we forget that you can go to another country and they’ll be like, ‘well, we’ve got all of our own pop music and charts. Why would we want your band?’ So except for the usual suspects, like Red Hot Chili Peppers, it’s pretty tough to come here and do a show. In Tokyo the capacity is 500 people, perhaps, and, like, Kode9 would fill that easily, three times over in the UK, but here it would be tough.”

The Kyoto show is followed by more signings, selfies and catching up with a few friends who’ve come to see Derwin from years back. It’s not late, but in the taxi afterwards he says that he’d normally be the first away from the venue, were this Italy or anywhere other than Japan. “I’d probably be in bed with a cup of tea by now,” he says. But this is Japan, and it’s Derwin’s friend Miho’s birthday, so in less than an hour, it’s corn dog hip-hop.

It’s in Tokyo where sushi is completely ruined for me, on account of how good and different it tastes compared to what they’re serving in M&S.

Of course pizza tastes better in Rome and tapas in Barcelona beats tapas in Basildon, but the difference between the sushi in the nothing-special-but-special-to-us restaurant we’re sat in and anything I’ve ever had before is staggering.

After four days of watching Derwin speak and read Japanese it’s still an impressive sight. He orders “a bunch of usual stuff” (salmon, tuna) and “a load of different things that we can just try” (deep fried oysters, eel, salmon caviar, flounder and sea urchin). Derwin has of course tried all of these before, and it’s a mark of his selflessness that he includes dishes that he already knows he dislikes. Everything tastes soft and fresh and incredible, apart from the sea urchin, which Derwin correctly describes as tasting like “a geography teacher’s breath.”

We have almost as much fun shopping in a department store called Tokyu Hands (Derwin buys gardening gloves and a blanket, I’m happy with some stickers for recycling bins (better than they sound), and Dan plumps for a small flatbed truck with a velociraptor on the back of it), and in a toyshop with a name that’s suspicious to us cynical westerners – Kiddyland.

Over breakfast on the day of Gold Panda’s Tokyo show (the biggest of the three at a raked, brutalist venue called WWW), Derwin tells me: “Japan has a nostalgia attached to it, but the thing is that after being here so much I’ve really become more interested in seeing England, to the point where the next thing that I’d like to do is travel around the UK. Because they’re quite similar,” he insists. “Despite us thinking that England isn’t very good, if you ask my friend Ryo what he thinks about it, he loves it, because it’s complete freedom. Here everything works very well and everyone gets to work on time; England is a little bit more free and rough – less serious.

“The only people that bump into you here are other tourists. The Japanese people generally don’t bump into each other.

“I’ve not travelled much around the UK, but the more I see of it the more I see the similarities between a little shop in Chiba that sells all this junk and places like that are everywhere in the UK. Charity shops in little towns filled with tat. People just selling fish and chips in a chippy is just like coming here and finding a place that only sells Kushi Age [deep fried cheeses, vegetables and meats on wooden sticks]. They’re the same things.

“I used to think it was so different, but now I see the similarities. Like, everyone’s a little bit racist, and foreigners just get in the way. We stand around on the bullet train taking up space and not getting into our seats quick enough, being really inefficient.”

The first thing I did when I landed in Japan, as embarrassing and Hollywood as it is to admit, was listen to ‘Good Luck And Do Your Best’. I suppose I wanted to see if an album that is so inspired by one place would feel any different – any more heightened – when listened to there. I’m none the wiser, no doubt because I did this in a fucking airport on half an hour of crumpled British Airways sleep, completely unaware of what day of the week it was. I know that it sounded it good, but the trademark warm crackle of Gold Panda always does.

Derwin points out that it would be impossible for me to make a call on that anyway – the story of ‘Good Luck…’ (how the title came from a taxi driver’s parting gesture in Hiroshima, and all the rest) is in me and that’s that. Most albums, he says, are sold with a story, from the artwork to the track titles, certainly to the lyrics.

“I don’t think my music sounds particularly Japanese,” he says, “but it’s got the repetition that I feel like Japan has visually. It’s got the feeling I want to capture about Japan, but I don’t want my music just to be about Japan. It’s just a place I like to escape to. That’s when I feel like I’m ready to create more music.”

He says he’s inspired by the way Japan looks, rather than how it sounds. “But it’s weird being a musician here because is it some appropriation that I’m doing, or am I saying to Japanese people, or to myself, ‘this is really good, you probably wouldn’t notice this anomaly if you lived here, because it’s just a machine that sells tobacco, but it’s actually really cool’? It’s mainly older stuff that I like. The ticket machines.”

Indeed, the technology that we’ve admired the most on this trip hasn’t been the AI robots in the perfume stores and toilet seats that play ‘privacy music’ when you sit on them, but the ramen restaurants with the serving trays that whiz to your table on magnets and the underground ticket machines that date back to at least the 1970s. This technology appears to have been so far ahead of its time, and so well made, that it’s never needed to be updated, and Japan has therefore retained its character and retro-futuristic allure. It might explain why a MacBook is distinctively missing from Gold Panda’s live show, and why Derwin chooses to rebuild his tracks with two identical, old fashioned MPCs that he is dexterous at driving.

“I’m happy to go home tomorrow,” he says. “I love it here, and I’d like to stay again for 6 months or something, but living here is not for me. I’ve done it and in England and London, despite Brexit and the atmosphere that’s portrayed by the media, it’s pretty free and accepting, compared to Essex when we were growing up. In London you can wear what you like and people don’t give a fuck. Here you stick out and you’re very aware of it. You feel like you’re towering above people. I don’t know about you but I feel clumsy in Japan.”

I’m not surprised to hear that Derwin will be happy to fly back to London after tonight’s show. For all the talk of foreign influence and exotic inspiration, home has always been central to Gold Panda and his music. His first and third albums were, after all, recorded at his family home in Essex; ‘Lucky Shiner’ was named in honour of his grandmother; even ‘Half Of Where You Live’, although recorded in Berlin, came with themes of place and belonging, from its title down. “Going away, getting inspired, not making music for ages and then getting really ready to go home and make lots of music – that’s how I do it,” he says. This has been the lasting appeal of Gold Panda, and Derwin’s humbleness is audible on his particular brand of dance/non-dance music and vintage samples.

As Loud And Quiet writer Reef Younis wrote of ‘Good Luck And Do Your Best’ this year, “Few capture contented loneliness quite like Gold Panda.” I read that back to Derwin as we sit in a street in Shibuya. He nods approvingly. “I strive for loneliness,” he then laughs. “I think there’re a lot of positive things about loneliness. It’s always seen as a real negative – some people are happy to be alone and do their own thing. People think that happiness will suddenly be bestowed upon you by meeting a partner and starting a family, but that’s a real lie.”

While we’ve been knocking around Japan, buying a load of crap for friends back home who won’t fully appreciate the wonder of miniature coloured wheelbarrows and hardhats, once or twice Derwin has pondered what he might do next, and if it includes Gold Panda, or perhaps even music at all. On our first night in Osaka he said, “I’ve been thinking about getting a job.” When I asked, oh yeah? Doing what? He dryly replied: “I don’t know, it’s probably just a pipe dream.” On the subway we discussed his idea of putting Gold Panda up for sale. Name, music, royalties, web presence – the whole lot. The concept being that if an aspiring Deadmau5 can supply their own Gold Panda suit, they could probably turn the whole project into a faceless, dumb EDM project and tour the world to make hundreds of millions at Spring Break. I’ve heard more ridiculous plans, and it’s really no more nutty than buying a bar or a house in Japan, which Derwin also mentions in Kyoto.

These ponderings all point to a musician considering his next move. Originally he wasn’t sure whether to release ‘Good Luck…’ as Gold Panda or under a different name, although he says now that he’s glad he chose the former.

“I’m happy that I’ve done these three albums and I feel like I’ve seen through what I started with ‘Lucky Shiner’,” he says. “This record definitely feels like the closure of that period, and it might be the closure of Gold Panda – I’m not sure.

“I’m definitely going to park Gold Panda, palette wise,” he adds. “You know, 11-track albums with an arc, that’s over. But I’m still working out if anything I do is Gold Panda, or if it’s this certain sound. I’ve worked hard at this for so many years, should I just continue the name and do whatever I want, and be prepared that some people won’t like and others will like it more? Because when I started Gold Panda, I chose the name because it sounded like the music I make – it was warm and fuzzy. Pink Worm [another name he considered] would be an industrial group. It was a bad thing to do, because now the music has to fit the name, for me.

But I feel free from the pressure now,” he says. “I feel like I should just believe in myself a bit more.

“The new album gives people a complete package of this music. There’s no reason for me to make another album in this style. If you want to hear music that sounds like old Gold Panda, just listen to these three albums and the 20-track compilation – there’s plenty of music there.”

The show at WWW sees all of Derwin’s friends turn out, including Mayuri, Ryo and Miho. It’s the biggest and best show of the short run, and punishingly loud. Afterwards, a few of us go to a dive bar called The Legless Arms. As we enter, Derwin’s friends clap and cheer. The owner leans over the counter top to embrace him before putting on ‘Good Luck And Do Your Best’ and goading Derwin to sign the wall with a thick marker pen.

It’s a rare moment when Derwin allows himself to quietly acknowledge his musical talent. “I’m finally coming to accept that I have some tiny bit of musical ability,” he says. “A molecule. A Ricicle, really.”