Dubbed-out, mugged-up: time travel with David Keenan

With his new novel Industry of Magic and Light, the Scottish author and DIY music evangelist is embracing the cosmic potential of small town subculture

With his new novel Industry of Magic and Light, the Scottish author and DIY music evangelist is embracing the cosmic potential of small town subculture

Art is magic and magic is memory. Spend enough time with evangelistic, Airdrie-born author David Keenan and you will be convinced of this.

“Belief in art is what moves me because I know it changes people’s lives,” a fervent Keenan says with a glint in his eye as he sets off on another passionate monologue. “It’s truly magical, that’s why people fell in love with This Is Memorial Device, because it trades on memories of every small town we grew up in. If you cared about art and you transformed your life to do it, that was actually bolder and braver than Iggy Pop doing it.”

Keenan is talking about his debut novel from 2017, the now-cult-classic This is Memorial Device, a transformational piece of work that hurtles deep into the fictionalised post-punk music scene of his hometown in the late 1970s and ’80s. Three dizzyingly brilliant books from Keenan followed, but only now do we return to Airdrie for a Memorial Device prequel set in the 1960s.

“Ever since I was a kid I was reading critical rock books, fanzines, comics, sci-fi films…” says Keenan. “The DIY thing came out of that and got me into underground music and it’s still where my heart is. This is very much what [new novel] Industry of Magic & Light is about – the cultural heroism of partaking in the moment.”

Why, then, is the new book set in the 1960s, before Keenan was born and long before he began engaging in such heroism?

“I have always collected original ’60s albums and poetry, so I decided to write my own version,” he says. “Even my novel, For the Good Times, set in Belfast in the ’70s, was an alternative take on the past, engaging with history on a micro-level. I use the ’60s setting to reveal primary artefacts of the time and create an inventory. I own original letters from the American poet Jack Hirschman and I was gifted an entire collection of hand bound early Rolling Stone magazines so I was reading these as I was writing. The personal ads were so evocative. I realised the thing that was advertised the most in Rolling Stone were waterbeds – waterbeds were so big then, man – so they became part of the story. Just like Memorial Device, you are using fiction to get deeper into what really happened and I believe you can do that, that’s one of the great powers of fiction.”

Keenan relishes the hippy life. Aside from when he satisfies his voracious reading habit, he tells me he’s never been happier than when growing his own veg or building wooden huts in his backyard; the spiritual connection to the ’60s doesn’t seem far-fetched.

Keenan relishes the hippy life. Aside from when he satisfies his voracious reading habit, he tells me he’s never been happier than when growing his own veg or building wooden huts in his backyard; the spiritual connection to the ’60s doesn’t seem far-fetched.

“People like [philosopher and counterculture icon] Alan Watts changed my life, and psychedelic music is everything to me. I wanted to write a hymn to what a magical moment in time that was and also a requiem for its passing. We are moving away from that amazing point in time where, much like Memorial Device, small towns were temporarily transformed by culture. Now these places, even the Airdrie that I love, are not the same, culture is not there anymore and if it is happening behind closed doors you don’t see culture on the streets like the ’60s, ’70s, ’80s when the tribes were there to be recognised.”

Before fiction came a career in music journalism, and Keenan felt compelled to return to that world for Industry of Magic & Light, turning his critical gaze to one of his own characters’ record collection. “I wrote reviews for the weirdo records he had, whether it’s Alice Coltrane or Moon Blood by Fraction. It was all in my high-energy review style and I loved it. The revelation for me was that it’s the same thing – a similar evangelism in everything I do. Music writing teaches you to write in a psychedelic way; I think you have to step up to the plate and write something that lives up to the music, reads like the music, feels like the music. I realised that my novelistic mission is exactly the same.”

Looking back through Keenan’s work, you can trace this musicality, whether it’s in the construction of his sentences or a more literal approach to song. “Take my book Xstabeth: you can hear guitar chords at some points where I try to turn literature into music. It’s one of my favourite books and it remains inexplicable to me.”

A key influence on Keenan’s dedication to subculture was American rock critic Lester Bangs, who “changed my life. I know his writing off by heart and I listened to every record he recommended. I wasn’t into critical analysis as I wanted to read people who could write as good as my favourite records [sounded]. I like Lester Bangs writing about Lou Reed as much as I like listening to Lou Reed.”

If it wasn’t for Bangs, Keenan would never have published his own fanzine aged just 16 – “We were into a lot of good indie music at the time, like Orange Juice, The Pastels and Josef K, but we were also into stuff like A Guy Called Gerald; it was a really exciting time” – or written to Spiral Scratch and Melody Maker.

“[Those publications] liked my writing and it went from there. I moved to London, as my girlfriend at the time got a job producing the John Peel show, so I got to hang out with him quite a lot. I was really into experimental music and I wrote a piece for Melody Maker about Keiji Haino, which [The Wire editor] Tony Herrington loved. He left a message on my answer machine saying would I like to come and write for them. It was a dream come true; the next day I had to go in and meet Tony, and he never fucking turned up. But after that I wrote for The Wire for 25 years.”

It was at The Wire where Keenan found his voice, helping refocus the influential publication away from its initial exclusive emphasis on jazz towards a wider range of experimental and psychedelic music. While writing for the magazine in 2009, he coined the term ‘hypnagogic pop’ to describe a group of musicians who resembled “pop refracted through a memory of a memory”. A maelstrom of hate followed, labelling ‘h-pop’, as it was sometimes known, “the worst ever genre created by a journalist”.

“People get annoyed about anything, don’t they?” says Keenan. “All I am doing is writing about things in an interesting way. To me James Ferraro and Spencer Clark were just fascinating artists. It was a discussion with James, where we were comparing his music to the sound of disco filtering through a wall and he said it was like his dream memories of growing up inside the pop culture of the time. I just thought it was so original and brilliant what they did, pop music in the periphery of articulation. I still love the idea of it, approaching pop in a very dubbed-out, mugged-up, psychedelic way. It ties into my books, memories of memories of memories.”

The power of remembrance resonates through Keenan’s work, an artist himself who arguably trades in nostalgia, just like hypnagogic pop. “I think it’s different as I keep it alive, my books are not about those eras, they are presentations of those eras. For the Good Times [set in 1970s Belfast] isn’t about the Troubles, it takes you to the Troubles and you experience it. There is not one stance on anything, otherwise it would be mere nostalgia; what I do is present the era in all its complexity. I still believe that literature can travel through time, can put you there completely. It feels even more real than it was, you can go to a place in Airdrie where something didn’t happen but get closer to what actually did happen in those times. It’s mad but true. In a way that’s what great music journalism does; it takes you to Ludlow Street in 1965, where Tony Conrad is living with Lou Reed and Angus Maclise – it takes you right there.” That, we can agree, is pure magic.

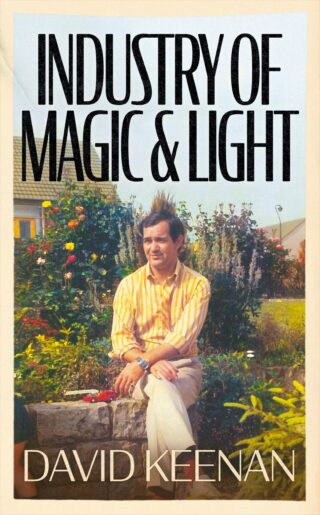

Photography by Heather Leigh