The Guy Out Back

Whether you take The Doors, The Stooges or The Ramones as the birth of American punk rock, they all owe something to a guy called Danny Fields

Whether you take The Doors, The Stooges or The Ramones as the birth of American punk rock, they all owe something to a guy called Danny Fields

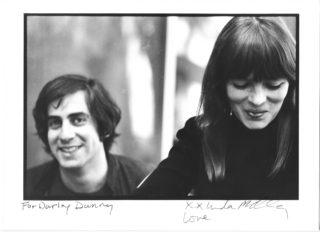

In the email exchange in the week or two leading up to my interview with Danny Fields you get the impression you’re dealing with a real character, an eccentric perhaps. After finally deciding on a city and day to do the interview (Liverpool on a Friday) Danny tells me of his plans to stay up continuously on prescribed upper meds from the Wednesday, when he flies in from the U.S., until Friday for our interview, so he can reach maximum delirium and sleep deprivation for our conversation. He asks for personal details about myself so he can know what to expect of me and inquires what my preferences and leniencies are when it comes to drugs. I fully expect to arrive in Liverpool to meet a deranged, drug-ravaged lunatic who hasn’t slept in days, who will thrust a variety of pills and powders into my hands, face and nose the second I walk through the door. I envisage dark times and a lost weekend ahead. However, in advance of our meeting I watch Danny Says a new documentary on Fields, the one-time Ramones manager and man responsible for getting The Stooges, the MC5 and Nico signed to Elektra Records, and I see a pretty genial, relaxed and entirely sane elderly gentleman recalling his life story on camera. Then again, I also find out that he once gave Jack Bruce acid-laced popcorn and was the first ever person to be censored on public access TV for pretending to stick a light bulb up someone’s anus. So, I travel to Liverpool (where he is being interviewed on stage as part of Liverpool Sound City) even more unsure of what, or who, I am about to encounter.

As Fields welcomes me into his hotel room, it’s not the makeshift drink and drug den I had perhaps thought it would be but instead much like anyone else’s hotel room – a half unpacked suitcase on the floor with various electrical items charging and a sterile atmosphere cloaking the air. Part of me is relieved and the other slightly disappointed. Danny’s voice has gone somewhat from picking up a chill on the plane so his plans for staying up for three days straight until he is barely making sense have fallen by the wayside. Instead he becomes fixated on the lighting in his room, which is admittedly dark, which he hates. He points at all the various pictures and diagrams of the Titanic that adorn the hotel walls in bafflement, describing it as celebrating a colossal failure, and he gushes of his love of Eurovision, which he intends to watch with glee the following evening. We talk for three hours in a very relaxed and detailed manner about many aspects of his life whilst sharing white wine, Fields sitting calmly in his slippers, not, as it turns out, hanging from the light fittings, barefoot with a head full of drugs, and me fearing for my own life and sanity.

“There’s nothing to cringe about,” he says of the documentary, directed by Brendan Toller, who also directed the music documentary I Need That Record! – a 2008 release, which focused on the future of independent record stores). Danny Says is littered with complimentary talking heads from the likes of Iggy Pop, actor-director John Cameron Mitchell and Patti Smith collaborator Lenny Kaye, as well as hilarious anecdotes. The film is ostensibly about Fields, but just as much about the fertile explosion of music in the late ’60s and early ’70s in New York, of which Danny was at the helm and a significant driving force.

You soon realise where his appetite for uppers comes from – growing up his father was a doctor who operated his practice from the house, meaning a constant supply of different drugs was available. Amphetamine was a household regular back then, in the 1950s. “If anyone came in and had to lose ten pounds because it was summer they would just prescribe them,” he tells me with a voice not dissimilar to that of a modern day Iggy Pop; slow and croaky, rich in texture and resonance and coated with a waxy vibrancy that somehow radiates a feeling that this is a person that has lived hard.

“The salesmen were beating down the doors of the doctors’ offices,” he says. “It makes you all chatty and happy – there was a bowl of them on the dining room table. It was like candy because they came in all different colours.

“I would stuff my pockets with these pills and give them to everyone. I was acing everything at school, just memorising the stuff. I was zooming through academia with A’s, being smart, plus this enhanced memory from the speed was something else. I’ve been self-medicating my entire life.”

Fields also had a rare insight and knowledge into the drugs he was taking through a “PDR” (a physician’s desk reference), “which was a book containing the pictures and information of every pill available that was not available to the public. My dad had it, so I would read through it just deciding which pills to take.”

The acing through academia led to a place at Harvard Law School, although this was somewhere that Danny felt he didn’t belong. Even though, he was hanging out with openly gay people for the first time in his entire life (Fields himself is gay), he didn’t last more than an academic year before leaving for New York, feeling somewhat directionless. “I wasn’t inspired by anything. I was just an aimless 22-year-old faggot in New York.”

Fields ended up working a job at a publication called Liquor Store Monthly and simultaneously encountering Andy Warhol’s Factory scene. Edie Sedgwick was his houseguest for a few weeks when she was kicked out of her parents’ Park Avenue apartment. He then applied for a job at the teen-focused music publication Datebook thinking that the ‘pop’ they referred to in their job advert referred to pop art, not pop music. Despite not knowing a great deal about the latter, Fields swung the job as managing Editor through a list of name drops and sheer bravado. It was here that he caused a whirlwind of trouble for the Beatles by digging up the old “we’re more popular than Jesus” quote (which had been originally said sometime ago in a London paper but largely ignored in the UK) and re-printing it. On the front cover of the paper was a quote from McCartney about the U.S. (“It’s a lousy country where anyone black is a dirty nigger”) and one from Lennon (“I don’t know which will go first, Rock n Roll or Christianity”) and then pandemonium ensued that could not have been predicted.

“They never played in the U.S. again after that,” notes Fields, “so now I’m the person who broke up the Beatles. Of course I didn’t, but I kind of wish I had because they were a pain in the ass. I just wanted to make a bit of mischief; I didn’t want to break up the Beatles.”

Fields went from job to job, seemingly at random. He was fired from Datebook after his clear inexperience as an editor began to show, and he quickly blagged himself a job as the Doors’ official publicist. Despite Jim Morrison and him not getting along, and there being a tale of Fields supposedly kidnapping the singer and plying him with enough drugs to wipe out a herd of elephants, Fields was so affective in this role in getting them press that he was hired by the band’s label, Elektra Records, where he would then convince them to sign both The Stooges and the MC5. There’s a particularly memorable moment in the documentary in which Iggy Pop says Fields turned him onto cocaine, something that he took such a liking to that three days later he was breaking into Fields’ hotel room and stealing his stash.

“Iggy was funny,” he tells me, “although, first of all, I didn’t turn him onto cocaine, and it was news to me that he was the one who stole it from my hotel, too. I thought it was the cleaning woman or something. I had them wrapped up within a sweater and hidden. Not only did he take the fucking drugs but he took the sweater too! When I see him I’m going to ask him about that – you can replace cocaine but you can’t replace a beloved sweater. He thinks he’s remembering these things – in one of the books about him he talks about me taking him for a haircut and that I was dictating the way it should be done, but that never happened. God bless him but he remembers whimsically, occasionally… Although I did turn David Cassidy onto cocaine.”

Fields was fired from Elektra Records after he was physically attacked by the label’s Vice President and Artistic Director, Bill Harvey, for spreading (true) rumours about his daughter around the water cooler. “Such an asshole,” he says with a slightly venomous tone. “He was punching me in the head, but it was all build up, he hated the Stooges and MC5 and the Marijuana song – he wanted it to be this classy little folk label.” The marijuana song refers to the ode to cannabis that was ‘Have a Marijuana’ by David Peel & The Lower East Side, another one of Fields’ brainwaves that ended up about as successful as it was controversial.

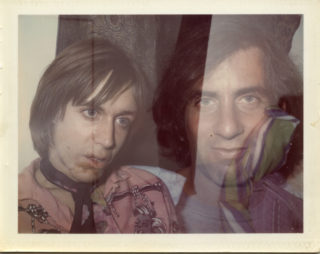

Around this time in the late 1960s Fields had been a journalist, an A&R man, a publicist, publisher, manager and much more, but he tends to be quite modest about his abilities in some of the roles. “Managing?” he says. “What the hell! I got them off the ground, I got them started or got them in the public but I could never follow through in Svengali-ing a career. What am I going to do? Tell them what to wear? What songs to sing? They were perfect. Am I going to tell Iggy what to do? I want to be surprised every time he performs, too.” Yet Danny does reflect on one particular moment with pride, of working with Nico, who he describes as “a mysterious moon goddess.”

“She was a great songwriter and my proudest achievement is the record she did with John Cale, ‘The Marble Index’. It was a 100 years ahead of its time and still is now. It’s very strange and odd. That album wouldn’t have happened if I didn’t drag her up there and get her in there with Jac [Holzman – president of the label].”

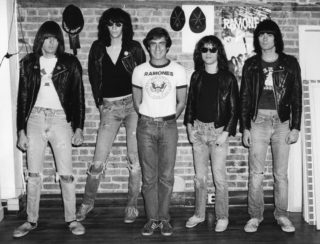

As the 60’s drew to a close, it wouldn’t be until the next emerging New York scene, CBGB’s, that Fields would take on his next major role, managing the Ramones, a group who he still has a huge amount of time and respect for. “They were not stupid in the slightest,” he says. “They were formidably smart, each of them in their own way.” Fields is keen to set straight the misconception of the group being a bunch of simpletons, and also debunk another myth of the group’s. “Johnny and Joey were millionaires when they died, so I would like to dispel the fact that they struggled until they died,” he says.

He lasted with the Ramones a few years before being voted out as manager after the band continued to find that ever-elusive pop hit that Fields was unable to bring whilst managing them, although he felt they were doomed never to have one from the off, because of their association with punk.

“The Ramones were killed because their first show outside of NYC, which I really struggled to get them, was in Boston and the college newspaper did an interview and Johnny said: ‘oh, so you were at the show last night? Where were you? I didn’t see you’ – because Johnny could spot someone out of a crowd of 70,000 people – and they said: ‘we were at the back’, and Johnny said: ‘well you should have been up front because that’s where we sound best’, and the guy from Harvard said: ‘we heard you vomit on the audience’, based on John Lydon apparently vomiting on someone somewhere, and from that moment I knew this was going to haunt them. Why would a radio station want to help a band have a hit if they’re going to come up to the station and vomit on your sound board or DJ?”

Fields’ departure was, however, apparently amicable. “There was no problem on a personal level,” he says. “I felt a bit jilted, but it was all very cordial. I was voted out 2-1.” Looking back on the musical legacy they left behind however, Fields remains gleeful in his recollections. “It was onslaught music,” he says, “it led us to hardcore but the Ramones had songs. It was a combination of power, volume, speed and melody as well as lyrics. They were never stupid, they were smart.”

Danny’s personal archive has been explored thoroughly for this documentary and some of the greatest moments come in the form of unearthed audio recordings. A phone call from Nico is one highlight, and there’s a brilliant moment in which Fields, whilst recording a radio show he did for WFMU, captures Lou Reed hearing the Ramones for the first time. “That thing with Lou listening to the Ramones is so incredible,” he says. “It went viral, it was used in a New York Times online article about my archive going to Yale. You heard a Lou that people never heard before – enjoying something, being friendly, being enthusiastic.

“Everyone was taping each other, [back then]. Those phone calls from ’68-’71 were a hoot.”

Not all of them, though. Nico would phone asking to borrow money for drugs. “Oh Danny,” Fields says, mimicking Nico’s unique deep voice, “I must have some heroin. Can you give me $10? I must have some heroin – No, Nico!”

Despite a life of self-medicating, heroin is a drug that Fields has largely managed to avoid. “Heroin is a bad, bad, bad thing,” he says, before recalling an experience with it that almost killed him.

“I tried it,” he says. “I snorted it and it was a nice, warm feeling, but I wasn’t especially wanting to do it again, but someone convinced me to do so and I almost died. It was a lot stronger and I had kidney failure. So, I was like, what did I get out of this that was worth nearly dying for and having fucked up kidneys for the rest of my life? Nothing. It’s not worth your life.”

Life is something that Fields [now 74] has seen disappear in front of him over and over again through the years. Many friends, colleagues and acquaintances from that era have since passed, and did so a long time ago and prematurely. “It’s horrible to lose someone and there are so few people left that are okay and smart enough to laugh with and to talk to. It never stops being horrible; I’ve been devastated and paralysed by it. Nobody can take the place of someone that has been in your life for a period of time. I miss my dead friends and I wish I could pick up the phone. It doesn’t get less as you get older, it gets more. Now I’m in the death zone – anyone my age is rolling towards the cliff. In one year [2013] five people died. I have no friends left, my best friends are gone.”

Danny Fields is a unique character in the music industry: omnipresent and important; unquestionable yet impossible to define. “Danny is a connector, like a fuel injector in a car. He brings all the elements together for an extreme explosion,” says Iggy Pop in Danny Says. He’s a product of the times and the most interesting thing about talking with him, or watching the film, is that tracing his story leads into the story of so many others. By having this ever transient role and working with so many interesting people, and by the sounds of it taking so many drugs and creating so much havoc along the way, he is like a great supporting actor, more noticeable in the tales of other people’s lives than he is a star of his own. However, as Danny Says starts screening in the UK, his rich, historically and culturally significant personal archive has been purchased by Yale University and he is about to have a collection of his photographs put together for an exhibition. It seems that 2015 may be the year that people begin to know the story of Danny Fields.

As our conversation wraps up, I try to get him to pick out a highlight or two of his time shaping the story of rock’n’roll and punk.

“The Grateful Dead at midnight at the Fillmore, on acid. You’d go in when it was dark and leave when it was morning. They’d play for five hours or so. That was memorable. We were transported.” He says it was almost as memorable as the musical explosions that took place in ’66 and ’67. “Every band and every album sounded different – you were drowning in riches. It was glorious. I think it was a high point – in the next thirty years that I was in the music business there were never years like that. The harder psychedelic drugs were coming in and that period was golden to me. Nothing could ever be that rich. I think it’s going to take another 50-100 years time to figure out why there was such creativity then.”