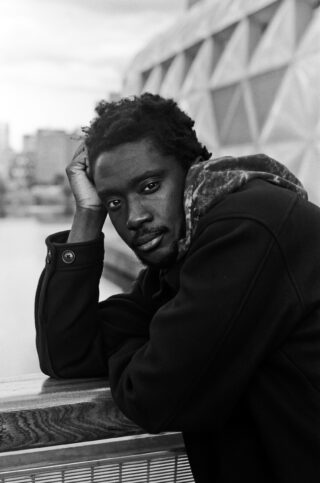

Coby Sey: “The key thing for me is not to limit myself”

Post-grime, post-punk, people power

Post-grime, post-punk, people power

He says it himself: Coby Sey isn’t afraid to take his time. His debut album, Conduit, has been five years in the making, and he’s deliberately avoided committing to music full-time for most of that period so he can keep his passion for it pure. But that doesn’t mean he hasn’t been busy.

The obvious place to begin a discussion of Coby Sey’s work is with his collaborations. From Mica Levi to Kwes via Klein, Kelly Lee Owens and Kevin Martin, Sey has been a consistently innovative figure on the experimental fringes of London’s underground music scene for several years now. He plays in Tirzah’s live band as well as working closely on her records, and has contributed vocals and production to records by the likes of Babyfather and Cosha. He’s also worked extensively on film scores, most notably for Steve McQueen’s acclaimed Small Axe anthology in 2020. Around his day job as a web developer and designer, those projects have kept him more than busy enough for the last few years.

“I’ve been working on this album for quite a while, but I [also] haven’t been working on it,” he says. “I mean, I started working on it in 2017, but I’ve taken five years because I was busy working with other people for their projects. That’s pretty much the reason why it’s taken this long. But you also have to recognise the realities of attempting to work as a musician or within the arts. In London, in the UK. It’s not easy. We reside in a society that isn’t set up for finding another way around the whole nine-to-five office job.”

On Conduit, the influences of all of Sey’s activities – professional, personal, musical – are clearly audible. The restless energy of the whole project is consonant with the rhythm and physicality of city life, evoking ideas breathlessly finished off before running for the bus to work; Sey’s aesthetic curiosity is reminiscent of his many experimental contemporaries; the complexity and cohesion of the record is testament to the amount of time and care that’s been invested in its creation.

Sey is very conscious of the way that his life and experiences seep into his work. “I think that kind of awareness comes from me just being really into music and being into people,” he reflects. “Not only being into the music but knowing how people perceive music. Whether it’s from an artist’s point of view, a producer’s point of view or an audience’s point of view – I’m genuinely interested in that. We don’t live in a vacuum, so there’s always going to be some sort of dialogue between all those different parts [of life]. You can’t have one without the others.”

Conduit draws upon a rich lineage of British music, from post-punk to grime via off-kilter, Aphex-y electronica. Yet more than British more widely, much of Sey’s work feels hyper-local, focused intently on Lewisham and the South East London suburbs where he grew up. The dense-yet-sprawling nature of that part of the city, from the modernist estates of Peckham and Deptford to the tight cul-de-sacs of Bellingham and Catford, looms heavily over this music; Coby Sey is audibly engaged with his home turf.

“No doubt,” he nods. “It’s interesting – I always wonder whether to describe myself with an adjective or a noun. Something like ‘British’ is a broad term – it can mean stuff that we love, it could mean stuff that we hate. It raises interesting questions: like, okay, what is British music? What is music that couldn’t be made anywhere else but the UK?

“But I’m easy with that side of things. I think I’d be more interested to know what other people’s definitions of that stuff are about. It would be disingenuous; it’d be a bit of a lie for me to not sort of recognise that [other people have different perspectives] as well. Because it’s not just British music – like, I’m in London, but I’m of Ghanaian heritage as well, and even within London it’s a big place, with north, east, south, west, south-east, south-west – it’s specific. You can always narrow it further, do a deep dive.”

The genre tag that gets thrown around the most when Sey’s work is discussed is ‘post-grime’ – and that’s geographically and culturally specific too. Just as the original grime movement was intimately connected with the shifting character of the estates of Bow, Hackney and Tottenham, much of the music that has followed in its footsteps, including the related but divergent strands of UK drill and afroswing, is tied intimately to its surroundings. Look at how inseparable 67 are from their Brixton Hill roots, or Novelist’s crew The Square, so vital to the resurgence of grime in the mid-2010s, who were from Lewisham. Coby Sey is doing something different to those groups, but he’s drawing upon many of the same fundamental influences, and his work is just as inextricable from its physical setting.

“There are some musicians within what we know as grime that I’m really into – like Kano is one of the most important ones for me,” he says. “The Butterz crew, I think they’re great; D Double E, of course. But would I consider myself post-grime? I don’t know. I like that it reminds me of post-punk, you know, because grime and punk have been compared for a long time. It’s almost like comparing your Joy Divisions and your Certain Ratios to, like, The Clash. You can see the link but you can hear the difference in their intentions and what they’re inspired by. But it’s one of those things – it depends what side of the bed one wakes up on, whether you see it as a benefit or as a hidden hindrance. It changes all the time for me; I think the key thing for me is to not be completely oblivious to it but not to feel like I have to typecast or limit myself.”

Many of the artists Coby Sey mentions here could be understood as part of the ‘musical lineage’ he explicitly talks about in the press materials for the album. When asked to go into more detail on what he means by that – on who is part of that lineage and how the tradition is passed along – he’s very forthcoming.

“I think of Tricky, I think of Cocteau Twins, MBV. I think of what my mates have created in recent years – Mica [Levi], my brother, Kwes. And going back further, the stuff I was into through my teens, that questioned what I was involved in then, like Miles Davis and Meshell Ndegeocello. I’m definitely aware of the weight that comes in releasing an LP. And for me it’s about continuing and honouring a legacy.”

The interview is conducted right in the middle of the UK government’s summer 2022 collapse, following an overdue resignation from Prime Minister Boris Johnson, so naturally the conversation turns to the state of the country.

“What a mess,” he laments. “But these problems were there even before 2010 [the year the current period of Conservative rule began]. It’s just exhausting, exasperating.”

Does he see a way back? A bright future for ordinary people in the UK?

“Yeah – I mean, I have to. And what I mean by that is that it’s something that we have to take on ourselves, because we all have a stake in this matter, even if it feels like we don’t. To me that means people power. I like to think I allude to that and talk about it in my own way on the track ‘Onus’; maybe other tracks on the album too, like ‘Permeated Secrets’ and ‘Dial Square (Confront)’. But I’m also mindful that that can mean different things to different people, depending on their headspace, depending on what they can do. Especially being somewhere where there’s a lot of pressure to survive, to make ends meet. I sort of think all of it can count in some way and ultimately is about being aware of our ability to change things, and to find a way to be perpetual and persistent.

And I have to admit, like, I did buy a bottle of Coca-Cola yesterday. Did I need it? Probably not. But me choosing not to purchase that, I think that’s a way of helping – you’ve got to pick your battles. And just knowing that every little decision that we take, however small or large, it counts. So it’s good to be aware of that and see how that can help change things and sort things out.”

He’s reluctant to be too prescriptive about how his fellow artists and musicians could be part of those changes. “I’d say ‘can’ rather than ‘should’. But you can literally do anything. But I think reflecting what’s within them as well as around them, some people are able to do both, some people just one or the other. Being aware of that and knowing that people are listening.”

With the new album coming out on leftfield label AD 93, and many of his projects occupying an experimental space far from the glare of the most nakedly profit-driven, exploitative parts of the music industry, it feels like Sey is secure enough in his niche to decide for himself how he wants to improve the world around him, even if he’s less comfortable telling others what they should be doing. Conscious of the relatively challenging nature of his music (“I know it’s not Ed Sheeran or Ariana Grande”), he seems content to maintain a cult following, at least for now. But he’s also frank about the fact that that’s the result of his natural inclinations rather than a conscious decision.

“I’ve always been a bit of a weirdo. I’m attempting to say it as it is and be positive!” he clarifies quickly. “When [London independent radio station] NTS started, it grew out of a night called Nuts To Soup, and I remember when I found out that Nuts To Soup were starting a radio station I breathed a sigh of relief that this was an outlet for people who were just as super-curious as me about music from wherever. To know that other people were into that sort of thing was such a good feeling. As to whether something gets more well-known – you know, whether I have a cult following or a bigger following – it’s not something I’m specifically aiming for. But if it did, I’d just be like, ‘Wow…’”

Interview conducted by Mike Vinti