Child Of Lov has made a pineapple camel funk album with Damon Albarn and Doom

That loving feeling

That loving feeling

Secrets are the gold bullion of the digital age. They’re a precious, fiercely coveted currency, the Bit coins that drive the gossip, fuelling the rabid demand to uncover the identities and revelations we all frantically seek. But where access and discovery are typically just a few clicks away, it’s made those little denizens of protection all the more delicious and exalted, and us, all the more desperate to uncover them.

These binary games of hide and seek don’t play out so nicely in terms of national security but they’ve always managed to thrive in culture and music. For some, it’s become an essential part of the package: Slipknot’s masked metal played perfectly into their Satan-lite pantomime, Daft Punk’s initial shyness progressed into one of music’s most stylised, successful brands, and even MF Doom’s increasingly lax man-behind-the-mask persona will ride out the fake show hits he’s taken.

For many, though, it remains a transparent, cynical schtick designed to generate a social buzz where the music can’t. There’s a fine line between the inspired and the derided but it’s one the enigmatic Child of Lov has been wilfully happy to tread. Buoyed by a trio of interstellar singles, and armed with a debut album set for release on Domino imprint DoubleSix, Cole Williams has been happy to let everyone else do the talking.

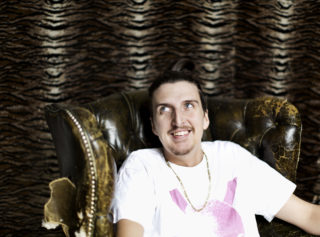

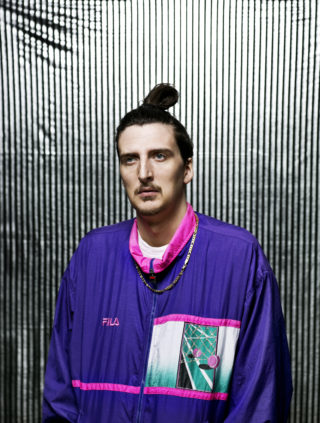

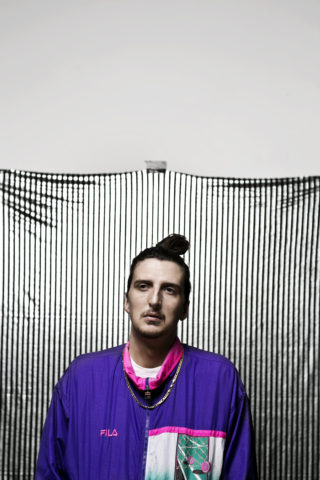

“The whole withholding a picture of myself was just to focus on the music for the first few months, but you get a little sort of itchy,” he smiles. “I was looking forward to not having to do that anymore because this way is easier. It feels liberating but I think the point was made.”

In an age of dissemination and disinformation, mindless exclusives, mind-numbing tell-alls, and the “leaks” that incite supposed outrage at the column inches they garner, the Child of Lov story should feel like another anonymity cliché. Instead, it’s the lead-in to the first of many contrasts that pit Cole’s personality and The Child of Lov dynamic against each other.

In terms of the music, the colourful references and comparisons have long flowed – from Cole’s self-coined approximations of “intergalactic R&B” and “pineapple camel funk” (whatever that means) to the equally mind-bending nu-soul, future funk, and spaceship-hop. What’s immediately apparent, though, is that his mish-mash of influences are worn on an equally colourful sleeve: there’s the power and vibrancy of iconic showmen like James Brown, the funk and soul of Sly and the Family Stone, the R&B vibes of D’Angelo, the skewed vocal melodies of TV On The Radio, and the contemporary gloss of Gnarls Barkley.

Conversely, it’s distilled, condensed and delivered with the spiritual howl of a laid back, 25-year-old Dutchman who doesn’t even really consider himself a musician. Already, it sounds the stuff of retro hipster nightmares simply because none of it adds up. Play the album to a group of people off the street, ask them to sketch the person behind the sound searing from the speakers and it’s unlikely they’ll draw a Zlatan Ibrahimovic look-a-like rocking gold weight medallions in Paisley-styled Versace. It’s at this point you realise this is the reason why Cole was so determined to keep his image concealed, and why the decision to let the music stand alone in the first place was undoubtedly the right one.

“A lot of entertainment isn’t about the thing itself anymore, it’s more about image first,” Cole muses. “It has its place, but to start off I thought it would be refreshing to do the first two or three songs, throw them out there and see what people thought of the music without the whole circus.

“You know, there’s Daft Punk, and we still don’t really know what they look like, and then you’ve got these other guys who exist in a bit of an anonymity realm, and then you have someone like Jimi Hendrix. His image was evidently important, even to this day, but you never get the feeling that the music’s not first, you know? You can really amplify things like James Brown did, as a big showman, but you just have to be conscious of it all.”

It goes some way to explaining the disparity in Cole’s archetypally lethargic European personality, and the all-action pomp and vibrancy that radiates from the record. There’s a sense of wildness and release but there’s also a conscious control to everything Cole invests into The Child of Lov. For all of the blood red suits, acid-casual artwork and hipster zeal of the videos, there’s also healthy homage and respect for the music he’s drawing upon. There’s an awareness that he only needs to be a showman when the time demands it, and the bold, colourful snapshots currently doing the rounds only (brightly) paint half the picture.

“I’m still waking up,” he grins in the photo studio at 11am. “I don’t usually record at this time so that’s the explanation. But you get into this place when you make music. There are different things in there… dark and angry stuff, and I like that a lot, and it’s in me as well, just not at times like these.”

It brings us neatly to his self-titled debut, ‘The Child of Lov’. Expanding on the spaced out booty infatuation of ‘Rotisserie’, the pop funk of ‘Heal’ and the pineapple-toting video of ‘Give Me’, it’s a firm reminder that for all the intrigue around his clandestine identity, the image and the hook ups, the building interest is still something Cole is trying to take in his stride. He admits: “It’s still weird to me. I still can’t get my head around it because I wasn’t making these songs for anyone, to get a response or to get any sort of feedback. I wasn’t trying to do that in any way, it just got picked up and I made this product out of it. I’m proud of the album and there’s a lot of good music on there but I’m expecting nothing, basically.”

Where The Child of Lov identity was a secret for so long, the involvement of Damon Albarn and MF Doom has not been so coyly protected. Recorded at Albarn’s studio, and boasting a long-awaited verse from Doom, it’s an album that can’t help but be built around expectation, and it’s a rare weight of line-up for any debut to bear. For Cole, they’re nothing more than positive factors; the outcome of a few network contacts as opposed to an albatross of expectancy around his neck.

“My manager managed Danger Mouse a long time ago, and he did some production on one of the Gorillaz albums, so that’s how he knows Damon,” explains Cole. “It’s not like he’s a friend of the family or anything but he got in touch and Damon was really into the music. That was really cool because a guy like that doesn’t need to do anything he doesn’t want to do, you know?

“Then it was kind of the same with Doom. It was through the DangerDoom album he was able to get to him. It took a year for him to deliver the verse but it was great for me, because he’s one of the few people alive I’m really a fan of.”

Cole is a lifelong hip-hop fan and needs little encouragement to talk about his influences. As he sips his coffee and gradually sinks into the sofa, it’s easy to hear how the fusion of soul, delta blues, funk and R&B blazed into the Child of Lov sound. A beat maker from his early teens, a combination of discipline and devotion underpinned the majority of his creative progression, and whilst his technical music education might have largely been one of self-taught discovery, his inspiration has always been consistent from the start. Most inspired by the Georgia sounds of Little Richard, Otis Redding and James Brown, the neo soul of D’Angelo, and a heavy dose of the delta blues, it’s little surprise that Cole’s listening habits verge more on the traditional than the contemporary.

“I don’t listen to a lot of music,” he tells me, “not compared to other people, but I listen to the same sort of stuff over and over again. My favourite album is probably ‘Voodoo’ by D’Angelo because it’s the album I listen to most. I listen to it once every few days, just trying to find the hidden harmonies and the things I didn’t hear before. That way of listening to music becomes part of you after a while and it’s the same with singing; you subconsciously try to model yourself on these great singers like Otis Redding and James Brown, so it just comes naturally after a while.”

It’s a simple, almost stubborn ideology, one that’s at odds with the modern desire to mindlessly download and acquire music instead of taking the time to appreciate it. It’s another in the Cole/Child of Lov contrasts; the bold bombast of the music masking the candid, almost analytical outlook beneath.

“I’m weird,” he laughs. “Well, different, or something. It’s weird to say that about yourself but I’ve been quite a solitary person all my life, never had many friends. I’m a special kind of person according to a lot of people in that I’m not bothered much with what other people do. I didn’t ever think of myself as a musician. I didn’t hang out with any musicians, didn’t really know any, I wasn’t bothered and I’m still not really.”

It’s a thought process that also extends to the wider perception of the album. Apathetic, bullish, indifferent, however you want to interpret it, all of the interest and anticipation that’s been building, in terms of Cole’s attitude to the wider reception to ‘The Child of Lov’ is decidedly black and white.

“I don’t give a shit about the fans, basically,” he deadpans. “It’s not intended badly, and I’m not trying to be blunt, but that’s the way I feel about it. I have the same feeling towards journalists and fans: if you don’t like it, you’re not really a fan anymore, are you? I’m pretty hard-headed.”

It’s less of an admission than you might expect considering The Child of Lov has never played a live show, despite the imminent release of a debut album. In an age where touring is the lifeblood for bands to make a living, it feels like even more of an anomaly considering the energy and spontaneity the album exudes. On first listen, the on-record flamboyance feels destined to inform a live set of show-stopping decadence; one of MCs whipping crowds into a neo funk frenzy of lights, camera, action, and wild party spirit. It’s a prospect Cole is remarkably unmoved by, preferring to focus on the long term perfection of the record instead of the disposable experience of the live show.

“I’m probably not supposed to say this but it’s not one of the important things to the whole act. Playing live is basically just promotion and you can create this different atmosphere, but if I wanted to do that, I could just record it and put it out on an album. To me, engineering is listening to stuff over and over again and having it exactly as you want. That’s music to me, not singing in front of a crowd with a few girls or something. It’s nice,” he smiles, “but it’s not the most important thing.

“I don’t mind being on stage and the showmen knew the importance of a great show, but it’s not about that to me. It doesn’t have any gravitas – it just comes, you drink too much, and it disappears again into nothingness. Recording something, putting it on tape, and documenting it, that’s a whole different thing to me.”

In our throwaway age, it’s a subversive attitude to eschew the idea of a live show for so long, but it’s an alternative view born from that hard-headed indifference. For Cole, it’s definitely not a case of being lazy, just one of being bold enough to buck the trend in both style and substance, despite the growing demand.

“I’m going to do sessions quite soon,” he reveals. “NME wants me to play, Glastonbury want me to play, and my booking agent said he hadn’t experienced this much interest at this stage in his 30 year career. I don’t want it to come across as though I’m slagging off live shows because I’m looking forward to it, I just want my live show to be meaningful.

“I got into D’Angelo when I was quite young so I was never able to see him perform live but I saw a show in Amsterdam last year and it was great. But it was great because the music was part of me already. Of itself, or in itself, a live show is cool and you can dance or whatever but that’s not what life’s about. It’s about these deeper realisations and emotions you can experience between you and an album, so in that sense, music is much more of a solitary thing to me.”

Again, it feels like this is another battle between Cole’s individual outlook and the mood The Child of Lov inspires. The album is a spirited, vivacious party record in every sense of the word; an all in invitation to the cosmic bom-chicka-wow shudder of ‘Give Me’, the cranked anthemia of ‘Go with the Wind’, the TVOTR falsetto bump of ‘Warrior’. An album to soundtrack summer heatwaves, be shared and revelled in, and sang into the night with the top down. It’s unquestionably a glorious LP of unashamed single fodder but set against Cole’s own expectations for what a live show should achieve, creating one that matches the audacious attitude of the record, and also endures and represents a considerable challenge.

“It was a lot easier than I thought, actually,” he says with a grin. “I think it’s got to do with where the music came from because it came from an ad hoc place, and a desire to create an analogue sound digitally with the crappy means I have. I didn’t have any money growing up, I didn’t have any instruments, and I even used to play the computer keyboard. Coming from that place, I think it translates really well, like it’s supposed to be like that. I’m not showing it too much to the band,” he smiles, “because they need to be on point. I think it’s going to be great.”

With rehearsals underway and a few dates set for the next few months, Cole’s optimism is bold, if untested. It’s also forced him to find ways of approaching a live dynamic that was never on his radar, and appraise the styles and techniques that have taken him from a happy unknown to a prospect for the coming months. So for a man content to wake up, drink coffee, and make music as part of a natural everyday process, digging deeper into what makes The Child of Lov musically tick, has forced him to consider the rough edges beyond the comfort of the studio, and really embellish the details.

“It’s nice conducting a band, it’s like producing in a different way,” he explains. “I find it creative and fulfilling asking for the snare to be tuned down a little or whether I want the cymbals in the last two choruses instead of three. I used to say that I wasn’t a perfectionist because I’ve never really liked styles. You have someone like Danger Mouse who is so neat and perfect, he’s a genius or something, but I’m not really into that.

“Working with the band now, it makes me really think about what I want. I think it’s helped me realise I’m a perfectionist but only towards other people,” he laughs. “We were rehearsing ‘Give Me’ the other day and that’s quite a sparse song, so it’s really about getting the vibe right. One mistake, one missed beat, and it immediately sounds like shit. But for a song like ‘Fly’, it has that dreaminess and that rough low end. We get that right and we’re good to go.”

So from the ad hoc indifference of the man making music for no-one, to the forward-thinking perfectionist ensuring his new band is on-point for the live shows he never intended to play, it’s easy to overlook that three singles and six months still represent an artist in his infancy. Faced with the fresh challenge of adapting and creating a live platform for the record should have been task enough but driven by the momentum of the first album, Cole’s wasted little time, or energy, mapping the journey of the next, confidently taking some of the inspiration behind ‘The Child of Lov’ and developing it for the future follow up.

He says: “There are two or three songs on the first album that I think progress into the sound of the second record. It’s not a retro record, I’m just trying to honour the old and reach out for the new. It’s kind of like a Sly and the Family Stone record, sorta old soul, and I think the second album is more specific in a way. It’s probably a more conservative sophomore album in that sense.”

At this stage, conservatism feels like the least likely outcome but where Cole looked to his influences once to guide and fire his debut, it seems they’re set to play an equally prominent, if more focused role on his second. It already feels ridiculous to be looking ahead to a second instalment when the Child of Lov story has yet to really begin, but for Cole, that search is already underway.

“I really like how D’Angelo’s first album was a general 90s R&B album,” he ponders as we gather our things. “It was new stuff but ‘Voodoo’ went back to the old stuff. It was the same with Sly and the Family Stone on ‘There’s a Riot Goin’ On’. It’s one of my favourite albums because it has this dark soulful energy to it but it also had a loneliness as well. I think I’m looking for that. I’ll just keep searching.”