Charles Bradley is the ex-James Brown impersonator who refused to quit

It took Charles Bradley 63 years to be discovered, which left a lot of time for him to experience more heartache than any one person deserves

It took Charles Bradley 63 years to be discovered, which left a lot of time for him to experience more heartache than any one person deserves

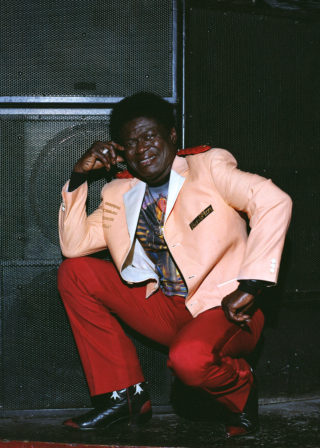

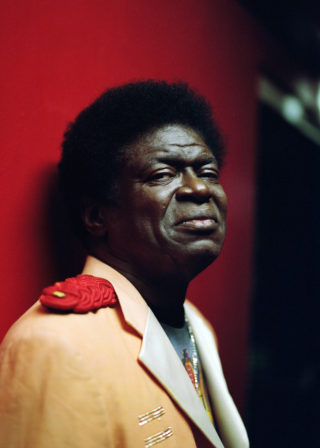

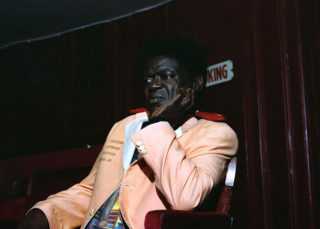

You’ve only got to look at Charles Bradley to see that he has suffered pain in his life. His face, at sixty-five years of age, is a strange amalgamation. At times It’s boyish, laced with a mischievous smile and a wide-eyed sincerity, yet it’s also weathered, tired, fear-drenched and sags with an overwhelming aura of sadness and hurt. For each deep-set, aged wrinkle that scores across his forehead like a knife wound, behind it lays a tale of unimaginable pain.

Not one to hold back on his feelings – both personally and musically – Bradley’s face is an accurate embodiment and projection of what he holds within. To stare into the eyes of Charles Bradley sobbing, is to see the physical manifestation of a lifetime’s worth of anguish and pain erupt in a human being. However, not always is this the prominent manifestation of Bradley. On stage he is a never-ending giver of pleasure, a non-stop dancing, thrusting ‘screaming eagle of soul’ and to see him lost deep in the midst of his performance is a transformative and occasionally nonparallel experience. Professing a message of love, peace, spirituality and equality, he soaks up the audience’s adoration and hurtles it back at them. (The first time I saw him, at one point his arms were outstretched towards the audience, as he screamed with every ounce of his being “I love you!” for what felt like ten minutes).

Bradley’s voice, at its incendiary peak, tears through you like the news of death – a scorched and ravaged Otis Redding. On his two albums, 2011’s ‘No Time for Dreaming’ and 2013’s ‘Victim of Love’, his voice is moving, gritty and raspy, yet it’s melded amongst the smooth retro soul groove of his impeccable backing band The Menahan Street Band. It is on stage that his voice truly comes alive, though; a whirlwind force that I’ve seen bring people to tears instantaneously as well as leave them flabbergasted and lost for words. Seeing Charles Bradley perform at Primavera Sound earlier this year, in what was one of the greatest performances not only of the weekend but of the six year’s I’ve been going to the festival, along with tonight’s performance at the Shepherd’s Bush Empire, as part of the Daptone Records Soul Revue Tour (also on the bill: Sharon Jones & the Dap Kings, Antibalas, The Sugarman 3, Saun and Starr, Binky Griptite), it makes perfect sense to see him mesmerising audiences and owning the stage he dances and stomps around, but the journey that brought him here was a tough one. In many senses it defies belief, and it also took him most of his life.

Bradley’s Grandmother raised him in Florida until he was eight years-old when he was then reunited with his previously absent Mother and moved to Brooklyn with her. By age 14 things weren’t going too well and Charles ran away from home, struggling to put up with his poor living conditions that included a small bed on a dirt floor of a dimly lit basement. He slept on the streets and would ride the subway through the night, sleeping between stops until the hard rattle of a truncheon would wake him up – a signal for him to get the hell off. He would then switch subway lines and ride the train again, repeating this night after night, sleeping as much as he could before being turfed off the train once more and before the morning light broke free and the crowds of people began to flow. It proved a testing time. “Everybody around that time was using drugs, shooting up and getting high,” he says. Thankfully, despite temptation, he avoided that road. “I was afraid of needles and my faith in God kept me afraid of needles so I never took any drugs.” Bradley admits to a mild flirtation with sniffing glue and smoking weed, which was enough to realise that drugs weren’t for him.

At sixteen he signed up for Job Corps, a free education programme where he would learn cooking skills. This period was instrumental for him and has become one of his fondest memories in life. “I was living in a dominant black neighbourhood and I went to Job Corps and there were whites and other races there and I was afraid because I never seen that living in a black neighbourhood all my life,” he says. “Job Corps always showed me love and was nice to me. Now, down in the hood, when someone was nice to you, something was wrong, so Job Corps, when they were nice to me, I was wondering ‘Why? What do they want from me?’ and all they were trying to do was be a friend and I didn’t know that. When it came time to graduate I wanted to stay but it was time to leave.”

It was during Job Corps that Bradley’s musical side crept out. At fourteen he had been taken to see James Brown at the Apollo and was so taken with the performance he would begin to impersonate him at home. After then, being told he looked like James Brown at Job Corps and given a little gin to loosen him up, he eventually overcame his shyness and sang for people in public. Taken aback by his talent they literally forced him on stage. He then formed a band but this would be short-lived as every member, bar Charles, got called up for the Vietnam Draft, ending the group after five or six shows.

Bradley ended up working as a cook in upstate New York at a mental institute in Wassaic. “I was feeding 3500 peoples a day,” he recalls from this period. (Bradley has a charming habit of putting an s on the end of all his words, perhaps part due to local colloquialisms and part due to the fact he was illiterate and only began to fully learn to read, write and spell in very recent years). “Looking at 3500 disturbed peoples a day, and then at the girls side they’ve got 4000 disturbed peoples – and I’m living on the grounds with them – I just couldn’t take it anymore. Some of the stories they [the patients] told you were just some sad stories, stories that will touch you to your heart.”

He drifted from city to city, ending up in California for a twenty-year period, playing small shows and making ends meet doing odd DIY jobs. His mother got back in touch around this period and asked that he move back to Brooklyn to reconnect their relationship. He did so. However, upon returning he got incredibly sick with a fever and was admitted to hospital. They filled him up with penicillin, which he is deeply allergic to and things took a turn for the worse. “I saw myself leaving this world,” he says. “I nearly gave up.”

He says that a visit from his brother was a pivotal moment in his change of attitude to hanging on in there.

“He came and he said, ‘Charles, if you don’t want to live for yourself, brother, then please live for me. Charles, I love you brother, you’re my heart.”

Bradley transferred hospitals, where they noticed the near-lethal levels of penicillin he had been given and packed him with ice in an attempt to break the still unknown fever. He was given several spinal tap (lumbar puncture) procedures, often as many as four in one day, a procedure he recalls as the “most painful thing I ever felt in my life.” Sadly, there was more pain ahead.

“What hurt so bad is when I got well and out of the hospital, my brother who loved me so much and took care of me, he got killed. He got shot in the head.”

We don’t speak about this in detail tonight but he once explained the horror of witnessing the situation. “A detective was standing in front of the door. He said: ‘You’re Joseph’s brother, ain’t you?’ I said: ‘Yes, I am.’ He said: ‘Son, please, don’t go in there and see your brother until we clean up.’ I said: ‘How can you tell me I cannot go in there? That’s my brother. I want to see for myself.’ God knows, man. When I walked in there… they shot my brother… they shot my brother with a hollow point bullet. God, I wished I didn’t go in there. I ran outside. I ran in front of every car and no car would hit me. Everybody stopped. I wanted to die. I wanted to leave this world. I could not take the pain. I loved my brother so much.” This horrific moment is recalled in his song ‘Heartaches and Pain’.

After his brother died, Bradley took on full responsibility of looking after his mother, who was then sick and getting older. He also took on the financial responsibility of paying for her upkeep and her mortgage too. After he’d moved back to Brooklyn, he began to perform as ‘Black Velvet’, a James Brown tribute act, after fully realising his ability to mimic the Godfather of Soul’s voice, moves and actions. Word – and video footage – spread and some years down the line Gabriel Roth, Co-Founder of Daptone Records, expressed an interest. During the 2000’s he worked with a few different backing bands, recording a handful of songs, before cementing a successful writing relationship with the pivotal Tom Brenneck and his Menahan Street Band, which finally led to his debut album release, at the age of 62, in 2011. It was successful, a documentary was made on Bradley’s amazing life (2012’s Soul of America) and his follow-up album in 2013 opened more doors as he gradually toured the world more frequently and, for the first time in his life, finally was able to make a little money from the thing he loved most in life. A deeply spiritual man, Bradley feels that God finally heard his prayers and gave him this late break in life.

In 2014, as I sit backstage, propped up on a medical bench in a makeshift interview room that is actually the emergency room of Shepard’s Bush Empire, with Charles Bradley, I expect a buoyant, on-top-of-the-world artist to be beaming ear-to-ear after yet another astonishing performance. Instead I find someone unable to escape a degree of pain that has punctuated so much of his life and while he is doing everything in his life to give out positivity and extending an unremitting degree of love to his fans, friends and family, he still has an up-hill battle against him. “My mom just passed away five months and seven days ago,” he tells me. “It’s like an emptiness because every time I come home I would always go straight to her.”

I wasn’t aware that his mother had passed and it throws me off guard. To have watched Soul of America again only the night before, and to see the bond and importance his mother had in his life, and then to find out she has just passed, is silencing. “The day she passed away they told me: ‘Charles, you’ve got a sold out concert,’ and I don’t know how the hell I did that concert.” He reflects on the moment. “I was in bed sleeping and my niece came knocking on the door but I was too asleep, I didn’t hear her. I always keep the phone next to me in bed, so she called and said ‘Nanna’s not breathing’ – oh my God, that was the worst thing I’ve ever heard. I jumped up, ran upstairs and went in her room and her eyes were just like this [pinches fingertips together] and I touched her and she was still warm and she looked at me before she passed. It was like a nightmare to me.”

Typical to Bradley’s amazing spirit and sense of resilience, he managed to take a moment of excruciating pain and transmute it through his art. “I said if I go on stage I’m going to fall apart. I went downstairs and I got into my old spirit and I spoke to my mom and she said: ‘Don, go into your dreams. Go out and do it.’ I said: ‘How I am I going to do it? If I get on stage I’m going to cry.’ I went out on stage and everybody gave me two minutes of silence. Everybody knew, I didn’t know how but they knew and I said: ‘God, give me strength to do this show’ and that was one of the best show’s I did because I would look out the corner of my eye and it was like my mom was standing right there. I know that was my fantasy and my belief but it really seemed like she was there and that’s how I got into that show and wow, it was one of the shows that everybody is still talking about today.”

It’s very easy to get bogged down in the seemingly never ending assault of sadness that has plagued Bradley’s life, but the genuine positivity and love he believes in and projects during his performances, in spite of the aforementioned hurt, is inspiring. “Everything I do I try to keep it clean and honest,” he says, “so I can give them [the audience] the love. So they can look into my spirit and see no negative – that’s what I’m trying to teach.”

Bradley’s never-ending stream of love has, unfortunately, before now, made him less than steady on his feet. “I’ve always been that sensitive guy,” he admits. “My mom always told me that she worried about me. She said I was too easy going and that she didn’t worry about her other children as much because my heart was too sensitive. She said: ‘Harden your heart a little bit son, because the world will see you coming.’” It’s a situation that appears to be coming somewhat true in the wake of his success. He says: “Sometimes I’m afraid of myself. Sometimes when I get a lot of love coming towards me, my heart will be pulling in so many different ways and I want to give to them all. That scares me because I won’t have anything left for myself. I get that way, I have to run some places and hide and recuperate, go into my thoughts and find a way to come back out again and face the world. When I’m home, sometimes I don’t want to come out. I go in that basement and I stay in that basement because now I have a lot of musicians pulling on me, saying: ‘Charles, we can give what you want in the music because we see that you are lacking in certain things and we can give you this…’ And they are coming in with their heart and it scares me because I don’t want to hurt what I’ve got so what I do is I run and hide because everybody is hitting on my spirits so hard.”

Coming from the projects in Brooklyn (a home he often had to leave when “things got too crazy” – in the documentary Soul of America we see his neighbour’s house plastered with bullet holes) he now returns something of a hero but that too has its downside. “Everybody thinks I have a lot of money but I don’t have a lot of money,” he says, sadly. “My mother [when she died] left the mortgage to me and I have to pay that and my mother has a sister who isn’t really stable. My momma asked me to watch over her and I watch over her. And I have a niece – her mother died when she was an infant and so our mother raised her and now she’s 22 and I tell her it’s now time for her to find a life for herself but she’s too afraid; she’s now leaning on me. I’ve got brothers that all think I’ve made it big in the music industry and are hitting on me and I say: ‘Wow, what do I do? Where do I go? What do I say?’ Sometimes I feel like maybe selling the house but then I say ‘no, no’. I’m in a moment in my life where I don’t know whether I want to go that way, that way or that way. I know that the music world and the business of the music world is a treacherous life – me, I just want to get on stage, rock the people, show the people my love, open my heart. But the music world is all about the greed of money and using me to get money from me. My music is built on my love – it’s the love that is pulling the crowds, not the money that is pulling the crowds, but they see that and they see that I’m a humble person and it’s scary sometimes; I don’t know how to deal with it. Sometimes I feel like saying, ‘no more music, no, I can’t take no more’…When they talk to me, now I’m a quiet person. How you and me are having a conversation now, that’s how I like to talk to people, but when they talk to me they talk like with more power, talking at me. Then I get quiet, I close up. They are saying, ‘Charles, I put you here, I gave you this opportunity’ – No! It’s my love [that got me here]. I thank them for it though, the journey, the love they have given me and the opportunity to get out and give people my love at these shows.”

Bradley’s second album, ‘Victim of Love’, seems an unbelievably apt title. Does he, I enquire, care too much for his own good? His voice breaks and drops very quiet. “I don’t know how to change it though. Sometimes it’s hard.” He stretches out the word “haaaaarrrrrd” to almost agonising lengths, his voice scratchy and breaking and his eyes lock deep into mine. “At the age of 65 it’s hard to change. I want to change,” he says, “I want to do what my mom says and harden my heart a little. I try, I do my best then I see one person, spiritually, that needs love and I open my heart.” He pauses. “I want to be able to give you some good laughing stories sometime but it’s not ready to come out yet.”

It’s at this point Bradley also informs me that his uncle died four or five days ago. “We had someone film my mother’s funeral and he died watching that, he had a heart attack and passed right there. I think he was mourning and he left.”

The more and more you consider Bradley’s life combined with his exorcising-like performances, you realise just how much of a physical toll having to go through those experiences night after night must have on a person. “Sometimes when you see me running to hide that’s when my filter is full and I have to run to recuperate my mind again and find love again to give,” he says. However, even when he returns home he’s not always allowed to rest. “The guys in New York that had me doing James Brown still want me to be doing James Brown because they were afraid to lose me. There are a lot of people down there [in Brooklyn] that don’t have the money to go to concerts and in the clubs I was doing they could come and pay $5 and come and see me sing but now they’ve taken me out of that crowd and put me in a crowd that can afford to go see the show. So some people have got a little angry with me – they say: ‘Charles, you’re turning your back on your peoples’. I said: ‘No, I’m not doing that. I’ve got to make a living, I’ve finally found a way that I can make a little money and pay the mortgage.

“I worry about my nieces and the kind of people they bring in the house, I don’t want those kind of people in the house but I see they are all coming around because they want to know who I am and they are getting in through my niece to try and find out who I am. They know that I am a singer and have seen me on the Internet and think, ‘oh, he must have a lot of money’, so they are trying to come toward me but I don’t want them to. If I see them on the streets I like to show my love and say, ‘how you doing, young man’ and a lot of them don’t want to work and a lot of them say that they want to work but can’t find work so they say Charles, if you need any work done for you in the house I will do it for you and they want to do things freely but I don’t take nothing for free. Me, I like to go home, into a nice quiet home – my main escape, I love listening to a tape I have of nature and sounds of the ocean and I will go home, get out of my clothes, make it dark, put the tape on and then I don’t want to go out and see that world out there. I know that I have my own space inside and if I open that door it’s a whole different world outside.”

Will there ever be a time in his life that his music can come from a place that is not pain, I ask, or is there just too much?

“I’m seeking that place inside of me,” he says. “I’m trying to find the light where I can come from the darkness and grow into the light and let some good memories come out of me but there’s not too many. The things that I’ve seen and lived through – there are not too many things in my life that I can say I can laugh about and look at them and say ‘wow, that was a good moment’. (He has at one point even said to an interviewer: ‘I’ve not even told you half of my trials and tribulations, some of it I just can’t speak.’). The best moment in my life I think was Job Corps, Job Corps was a beautiful moment.”

He speaks movingly to me about his time in jail, his first sentence for a dispute over a stereo that got him thirty days and the second for something far more serious. Working as a burger chef in a fast food place he confronted a customer who had complained about all three (separate, replacement) burgers she was given. He went out front and asked someone else how their burger was, the owner then told him not to come out and bother the customers. “You’re all alike,” she said to him, shortly followed by, “I’ll fix you.” The next day a big guy comes in the kitchen, throws Bradley against the wall, knocking him out cold. He refused to listen to Bradley as he pleaded, he then pushed him over the large, sizzling burger grill. He was overpowering him so Bradley grabbed a knife and swung at him – he didn’t cut him, but he did cut through his shirt. Broken free, Bradley then slipped, the guy continued to beat him, Charles found a pick fork on the floor under a freezer, seeing this the assailant then jumped off him – in the meantime the police arrived, put a gun to Bradley’s head and said, “if you move, you’re dead.” He spent “two to three months” in jail while the attacker was let go. “All my memories I take to heart, good and bad, because I know that I am not personally out to hurt or play with anyone’s intelligence, so I keep the truth and honesty of the person who I am and try and live that life,” he says, “but when things happen to me and people do me wrong, it hurts because like right now I have to go to Canada pretty soon and every time I go to Canada I got to go through all this high-tech stuff for something I never did to get a pass to go to Canada… for something I didn’t do!

“It’s something that happened in 1977 and they still give me a hard time to go into Canada. That’s still on me today and it hurts and sometimes I feel like saying, ‘no more! I ain’t going through this no more for something I didn’t do’. I’m getting brutalised for this all my life. I feel like saying, ‘no, I stay home’. The government is still saying that what I did was a felony but all I was doing was protecting myself, this guy was trying to kill me and all I was doing was trying to protect myself, when he pushed me over that grill and I felt the heat on my back, and this guy’s about six feet something, two hundred and seventy pounds, what are you going to do? You’re going to do something to get him off you, but the world is still holding that against me today.” He pauses, clearly in pain. “It’s not fair… it’s not fair to be hurt like that,” at which point he breaks down entirely into a sobbing fit. The only sound to be heard above his crying is the sound of his heavy silver chain slink down his wrist as he holds his hands over his face, shaking, as I sit there in silence.” I apologise for bringing him to this state. “It’s okay,” he says softly, “It helps me to talk about it and get it out.”

It’s difficult not to be lifted by Bradley’s resilience and forward momentum, even if it still seems to stall him constantly. “Through my trials and my tribulations.” he says with a soft smile, “I’m still going and I’m still strong.”