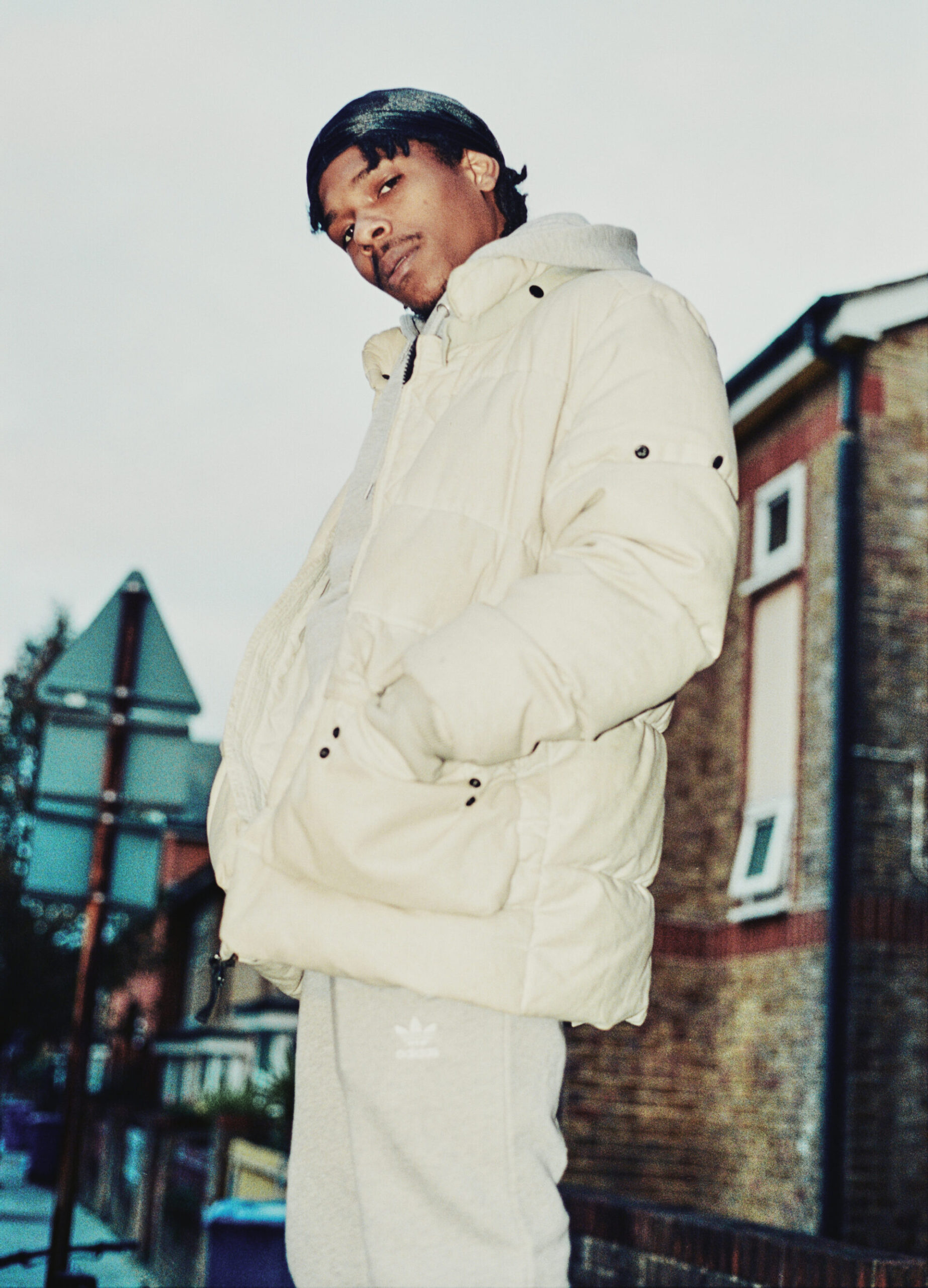

Berwyn: a unique young talent nearly lost to immigration papers

Influenced by his life in Trinidad and East London, the genre-splicing artist is keeping the faith

“I clung onto religious belief because otherwise who are you gonna believe in? Men? It was men that was letting me down, men that was making the decisions that had me in my position, so how could I put faith in that?”

When Berwyn Du Bois picks up the phone, he skips over the hello part, launching straight into the warm joviality and loud belly laughs that brim over through most of the conversation. But in the midst of talking about things like the easiness of dancing alone to R&B in front of the mirror, every now and again he will offer something slow and plaintive that recalls the searing insight of his music.

A multi-instrumentalist, rapper and singer-songwriter born on the Caribbean island of Trinidad before moving to Romford, east London, aged nine, much of Berwyn’s life in England has been marked by precarity. The “men making decisions” were the home office, with his mother being sent in and out of jail while he found himself in a recurring state of homelessness, all because they didn’t have the right immigration papers. But, against all odds, he came out of 2020 with an acclaimed mixtape under his belt, a Drake co-sign and a coveted spot on the BBC Sound of 2021 longlist.

“None of what is happening [with my career] makes any sense,” he laughs with exuberance. “I don’t think I’m special, but this shit makes no fucking sense!”

Contrary to what he might say, DEMOTAPE/VEGA is in fact a very special listen. The story goes that Berwyn made the project in his bedsit over the course of a fortnight – a final shot at seeing what he could make happen with his music in the UK (if it didn’t happen he would go back to Trinidad). It’s a significantly more accomplished tape than that hasty roll of the dice backstory might suggest, marrying hymnal sonics with the leftfield, echoey end of rap and soul, all while speaking candidly of his personal history, using gilded vocals that wax and wane between spoken word and song; intimate rasps and silken runs to convey romance and grief, relationships and the realities of how he and his peers were getting by (“Don’t let them catch you with the knife, don’t let them catch you without it”).

Music, of course, had always been a big part of Berwyn’s life. In Trinidad much of the calendar year revolves around carnival and devotion to music and, at several points, Berwyn sings sweet soca and parang songs down the phone. His father, who had previously been a DJ, made him have steel pan lessons as a kid (“there are worse things to be forced to do!”), and it was through his parents that he also came to respect everything from Motown to soul to Mika. When he arrived in the UK, he quickly began to forge his own taste too, watching the music channels on his auntie’s TV, namechecking Mario, Ne-Yo and those golden era Ja Rule and Ashanti tracks as moments that led him to start writing his own songs.

“With my immigration situation, I felt much futility in school,” he says. “I didn’t want to stay there, it didn’t feel like there was much point in my being there. So I picked music GCSE because I figured at least I wouldn’t have to try for no reason in that one lesson.”

And so, he had initially gone about his music lessons with the attitude that he could “not give a fuck”. His teacher was “the best guitarist in the world, but the worst teacher in the world – one of them ones,” he laughs. But then, after said teacher was fired for showing students The Human Centipede (obviously), teacher Di Russell joined and saw the potential in Berwyn. “Up until that point, the ‘options’ I thought I had [with my immigration status] were nothing to do with school,” he says, “But she put the time in and made me see I did have options.”

Nurturing his talent, Russell would take Berwyn and his classmate James to a folk club every Wednesday night, thus keeping at least one evening a week free from the potential trouble from those “other options”. The three of them began performing under the band name “Folking Young”, with Du Bois singing, as well as playing guitar and cajón. On other evenings after school, he was allowed to stay behind playing around with the music department’s singular Mac computer, with the caretaker checking in on him every couple of hours.

Although Berwyn still felt the underlying sense of futility about his future in the country, aware he wouldn’t be able to go into further education, he ended up studying music at college “for the love of it”. And while his friends disappeared to university, even self-releasing the tape he had put together in those two weeks was starting to seem impossible given his situation. But in the midst of it all, he managed to stay afloat.

“You have to have hope, that’s so important in any situation in life,” he says. “I was raised in a very religious household, so that gave me the upper edge to look up at the stars. Nowadays it’s more things like affirmations that keep me going. Maybe it’s just psychological, but maybe it is angels or something? I do have faith in my dad – I don’t think he’ll ever let me down. But I also know the extent of his ability. So it’s nice to put faith in something else…”

It was as if by cosmic or divine intervention that everything suddenly fell into place. XL Recordings behemoth Richard Russell heard his music and brought him on board for the second album in his collaborative Everything Is Recorded project (“a beautiful community!”). Berwyn signed with Columbia and, in June, he gave a stunning performance from home for Later… with Jools Holland, adding a harrowing new verse to his track ‘Glory’ with lines like “Lately I’ve been thinking a lot / How come cos I’ve never been shot my pain doesn’t count?”.

“It was a really weird space and time with my internal problems as well as everything that was going on externally,” he says of that performance, which came in the midst of the resurgence of global Black Lives Matter protests following the murder of George Floyd. “I asked for two weeks to write something, because I wanted to let the dust settle – you can’t predict that level of entropy, you know? There’s nothing I can say on that. But there had been some miscommunication and I found out the show was actually in like a day or two. So then I just decided to speak from my own story. And writing it was painful, but if I had been trying to write something with everybody’s weight on my shoulders I would have just given up. So I just said, ‘I’m gonna do this for the weight on my shoulders – it’s heavy enough.’”

In writing for himself, Berwyn’s work has still resonated with plenty of people. “There’s a girl who’s getting her cancer scan today,” he says, “and she’s been in touch with me through the treatment, because my music helped her get through. You know, I made those songs in two weeks, I was in no way expecting them to get on radio or for them to have this amount of reach! It fills me with a great sense of responsibility because the world is crazy, but I really have a chance to be, like, a little superhero or something? It’s intimidating knowing that every step I make is so crucial in terms of the ripple effect it might have on the kids who feel influenced by me.”

Though he is potentially interested in entering the more political sphere one day, for now he is dubious of the greater awareness and objection people seem to have of the hostile environment and government immigration. “I think I preferred it when people weren’t talking about it,” he says. “Out of sight, out of mind. In my music, I can talk about it on my own terms, because ultimately for all we might think things are changing because of what we see in our little Instagram bubbles, I know from experience that’s not what the majority believes. Otherwise Brexit wouldn’t have happened, and I wouldn’t get plenty of other indicators when I leave my house on a daily basis.”

For now, then, the focus remains on his artistry. “I made VEGA a long time ago, when I was so far from knowing myself,” he says, before laughing. “I’m a much better producer now! The music I’m working on right now is a lot more ambitious, I’m working with a few different sounds – for example some R&B polish. But I like making things my own, I like being a little inventor making little rearrangements to try make a more advanced product.”

He’s also hoping to put Trini sounds back on the map, he says, explaining that he is tired of the global assumption of Caribbean culture being solely wrapped up in Jamaican output. “There are such beautiful moments in soca,” he exclaims, “If I could just hone in on that. I would love to spend a year in Trinidad and build up an infrastructure with lawyers and labels and producers so that we could pave the way for the next global soca wave to take over. But that’s my little side job.”

Berwyn Du Bois might not believe in men, but maybe that doesn’t matter. He has faith in something else that has kept him going through it all.

Photography by Frank Fieber