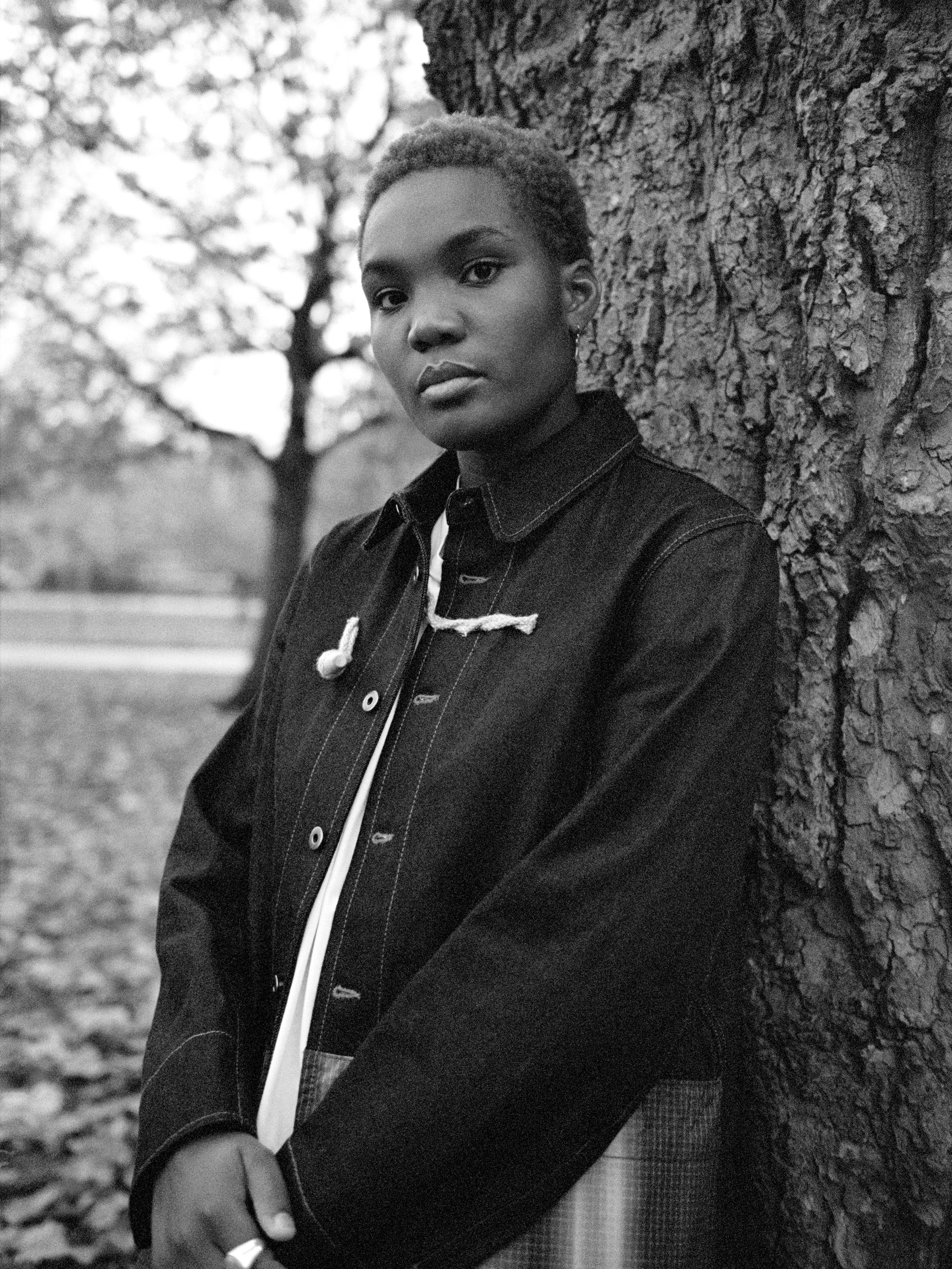

Arlo Parks – A young poet dissects her own feelings

The story of a vital debut album made in lockdown one, and released in lockdown three

Because of a wrong number mix-up, I’m ten minutes late calling Arlo Parks for our scheduled interview. While I bluster away with apologies, she’s understanding and sweet, putting me entirely at ease and so making an odd reversal in the roles of interviewer and interviewee. We go on to talk about this at length: Arlo sees herself as an empath, someone who is highly sensitive in identifying the emotions and pains of others and often taking these on themselves.

This goes some way towards explaining her music and the swell of popularity behind it. Her 2018 debut single ‘Cola’ was a stripped-back confessional detailing heartbreak and healing. Parks performed her recent single ‘Black Dog’ at The Glastonbury Experience 2020 – one of the few artists to be invited to play at Worthy Farm this year – and it catapulted her into a wider consciousness. ‘Black Dog’ is Parks reckoning with the limits of her own ability to help those around her, the sparse instrumentations and near-whispered vocals creating an intimacy that draws her audience in, hoping for healing through identification.

“I was just always very sensitive to other people’s energies,” she says. “It really affected me, and I always had that urge to step in and do something, help them. It’s strange to explain, but even in a social scenario with somebody that I don’t know that well, I feel like I can read the micro-expressions on their face and see if they’re upset. It’s quite tiring, to be honest!”

The opening line of ‘Black Dog’ (“I’d lick the grief right off your lips”) is, as Arlo terms it, “dismantling that saviour complex, as it were.” She’s very open about her own shortcomings and lessons learned from them, saying, “It’s a lesson that I’ve learnt over time – that idea that you can’t save someone, especially someone that doesn’t want to be saved or has their own things to process. I’ve grown to see that although you can of course be a positive force in someone’s life and encourage them to help themselves, the change does have to come from within.”

This idea of being a positive force for change is what drives her music career. She became an ambassador for the Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) over the first UK lockdown (“we really have to take care of each other”) and her upcoming debut album, Collapsed In SuArlo nbeams, is packed full of little vignettes that verbalise interior mental struggles so that they become easier to bear. ‘Caroline’ narrates a fight between a couple that Arlo supposedly overhears at a bus stop; ‘For Violet’ is a heart-wrenching plea to a friend (“Wait, you know when college starts again you’ll manage / Wait, you know that I’ll be there to kiss the damage”); ‘Bluish’ is about the difficulty of setting boundaries with someone who refuses to respect them. Her frank lyrics have provoked a strong reaction from fans; the comments on YouTube under the ‘Black Dog’ music video have people relating their experiences with suicidal thoughts, depression and the weight of Black masculinity.

“On one side of things, I definitely feel blessed that people feel they can approach me with the same emotional openness that I approach my lyrics with,” Arlo measures, “but it can be difficult. I’m grateful that my fans feel like they can trust me to that extent, but sometimes I do need to set boundaries because everything that I read does weigh quite heavily on me. I’m quite sensitive.”

This pressure to use her platform for the benefit of others was focalised this summer after the murder of George Floyd. As a Black queer person working in the music industry, Arlo says that she wanted to use her platform responsibly. “It was strange, there’s never been a moment like this where I’ve actually had a platform, so I just spent a lot of time thinking about how I was going to express myself, and just mainly giving focus towards Black joy and Black artists I thought were cool and trying to spread awareness in that way.” She pauses. “It was hard for me, especially because people were looking to me for certain answers or wanted me to be a voice for something. As a Black person, it’s just my lived reality. This is just who I am and have been since I was born.”

Whenever she is working through knotty or uncomfortable feelings, like those that arose at seeing graphic images of Black people dying circulating the internet, Arlo says she turns to writing. “I’ve been writing ever since I could, and for me it’s a source of healing,” she explains. “It helps me dissect my own feelings; especially with painful ones, it gives me a sense of purpose to be able to turn painful or melancholy situations into something that could bring other people hope. It’s just my favourite, I just love words!”

Arlo mentions feeling energised by writing that she identifies with when she reads the works of Zadie Smith or Virginia Woolf. “There’s this sense of natural excitement and playfulness in the way that I approach writing, and after I’ve written a stream of consciousness I do feel like there’s a weight off of my shoulders, or it feels as though I’ve created something out of nothing, which is a beautiful thing.” She links this to her very instinctual writing process, which fed into her work on her debut album. “I very much just follow my impulses. The whole process of writing a song, for me, is just me bouncing around excitedly. I don’t really sit down and sombrely ponder things. The energy carries into the music, definitely just because it’s very emotional for me. I’m literally riding emotional waves and strange impulses when I’m writing, and it comes from a very earnest place for me. There’s nothing that’s really constructed or false, it’s just me having fun.”

When it came to making Collapsed In Sunbeams, Parks holed herself up in an Airbnb in Hoxton with her producer, “incubated in the world of the record”, and managed to bash out an entire debut album over lockdown. She brought her teenage journals and notebooks to garner inspiration from, determining “which were the experiences that had shaped me and which were the traumas and the joys and the confusions that had marked my adolescence; that was the crux of the record.” She muses, “It was quite a free-flowing process, and most of the songs were written in a few hours, even an hour or so, and some of them were written and recorded in the same 24 hours. It was very much spikes of inspiration. That’s how I work, it feels like a lightning bolt strike. I rarely ponder over something for ages.”

In a sense, it’s precisely these strikes of inspiration that allow her to create work that’s relatively unbound from the confines of genre. Collapsed In Sunbeams carries elements of jazz, R&B, folk, indie and pop, which Arlo attributes to the mishmash of her parents’ tastes – her dad favoured Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk while her mum played a lot of Prince and ’80s French pop – as well as her own eclectic music taste, shaped by YouTube algorithms that led her to emo and indie music. I ask what her thoughts are on genre classifications, given that her work floats freely between them, and she says, “On one side of things, it’s useful in terms of providing a listener with the general world that an album operates in, but at the same time, all of my favourite albums are difficult to categorise in those linear formats. I don’t know what I would describe my album as if I were to say one genre. I guess maybe pop music?” She continues, “I’m pretty sure people have called my music every single genre, from indie folk to hip hop, so that makes me feel like I’m doing something right cos they can’t quite place it! There have been a few times when I’ve been put in the hip hop and rap category and I’m like, well it’s just not that, is it?” She then rattles off a scarily well-prepared list of her favourite genre-bending albums, including Radiohead’s In Rainbows, Portishead’s Dummy, Mama’s Gun by Erykah Badu and Syro by Aphex Twin. It’s an appropriate melting pot from which her own work has emerged.

Having made an entire debut album in the first UK lockdown, it’s more than fair that Arlo just wants to rest this time around. “I was giving a lot of energy out, so now I’m just trying to take it back in, to be honest,” she says. Reading is her primary way of doing this – she’s worked her way through Mrs Dalloway and Where The Reasons End by Yiyun Lee whereas during the first lockdown, she was reading heavy Russian literature – but she says she’s still keeping busy. “Keeping busy is taking care of myself,” she stresses. “If I just sit down, I will just not get back up for three weeks. I taught myself to DJ in the first lockdown, and this time I’m cooking, just making bread, making gnocchi, going for runs.” She laughs. “I don’t know if I’m being particularly productive, but just being active in some way makes me feel better. It’s just about trusting your body and doing what helps you.”

With a debut album campaign and a poetry collection in the works, she has much to rest up for. Talking to her, it’s a shock to remind myself that Arlo Parks has just turned twenty. She displays a wisdom and a self-knowledge that takes most people a whole lifetime to come close to; it’s both intimidating and strangely heartening. If Arlo Parks is what the next generation of pop artists looks like, that’s a very good thing.