Ariel Pink is still here, happily regressing in maturity

Growing down

Growing down

“Everybody gets involved with rock’n’roll when they’re so young that they’re bound to disgrace themselves at some point. I mean, if you don’t, then you really are a disgrace. It’s hard to do this with dignity for a long time. Even into your thirties it’s hard to do, but I’ve managed to disgrace myself from day one, so maybe I’ve got some lasting power.”

At 34, Ariel Marcus Rosenberg has been making music a majority of his life. The tipping point came some time ago, considering he started writing songs around the age of 10. A young Los Angelinos who continues to wear La-La Land with staunch pride, Ariel “strong-armed” his mom into buying him a cassette boombox and readily dragged her to local store Music Plus, where he acquired Deaf Leppard’s ‘Hysteria’, UB40’s ‘Labour of Love’ and Guns’n’Roses’ ‘Appetite for Destruction’. “From then I was sold,” he says. “I can’t remember not knowing my mum and it’s the same with music.”

In the some twenty-four years that have past, Ariel has followed a similar prolific path to that of his outsider hero and mentor R. Stevie Moore, writing and recording an countless number of songs that, like Moore’s, have wildly swerved from the sublime to the ridiculous. He’s released just 8 official albums (a pittance from a man with over 500 arrangements to his name), with a ninth, ‘Mature Themes’, coming August 20th. It certainly features a little of the ridiculous itself (‘Weiner Schnitzel Boogie’ is not the stuff of arch profundity), yet it’s quite possibly Ariel Pink’s best record yet; better, even, than 2010’s ‘Before Today’, an album that dipped its toe in the mainstream to great acclaim, and one that Ariel himself considers “a big failed experiment.”

Experimenting is what Ariel does, sincerely, these days with the help of his backing band, Haunted Graffiti. To praise him as some prince of lo-fi pop is to dismiss him as that, discarding his philosophies and doing the mechanics behind his music a disservice. It’s something I realise while talking with him over lunch.

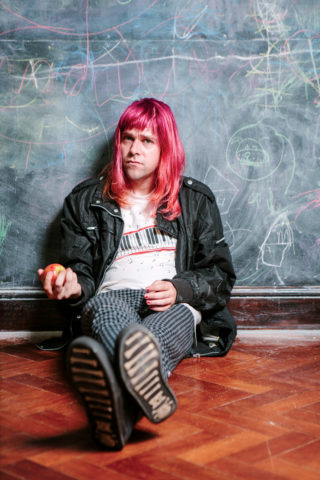

Beneath a freshly dyed hot pink do with a fringe cut too high, Ariel Pink is erudite and verbose. He’s shorter than I imagined, less stringy, slightly hunched and initially shy. He seems to enjoy answering questions, though, and once a plate of steak lands in front of us Ariel is the most conversational dining companion I could hope for. He speaks quickly and with a catching enthusiasm, the type of chat that would be deadly for a salesman. He regularly contradicts himself and freely admits that he’s that way inclined. He also seems constantly aware of his own age and the age of others. His new album is, after all, called ‘Mature Themes’.

“Oh, that was just a joke,” he says, looking up from the table. “You take life so seriously when you’re older, and this record has a focus on humour and sex and food and not trying to take things too seriously in any kind of artistic sense. But it’s got all the veneer of something that’s mature. We have the first single as ‘Baby’ [a dreamy, super slow cover of long lost sibling duo Donnie & Joe Emerson’s original], the album’s called ‘Mature Themes’, there’s this very artful picture on the cover and everyone’s getting ready for the new mature phase of Ariel Pink and the first thing you get is ‘Kinsky assassin blew a hole in my chest/Sea worthy vessel for the sperm-headed brain/mother twin genesis went down with the plane’ – y’know, just the ridiculousness of it!”

With such absurd lyrics engulfing the album’s opening three minutes, it’s little wonder that Ariel refutes the idea that his ninth album is his ‘growing up record’. “It’s my growing down record,” he says proudly. “It’s the product of a 34-year-old musician who’s still somehow relevant to 17-year-olds. It’s not adult, it’s a joke.” Yet ‘Kinsky Assassin’ is ‘Mature Themes’’s strange masterpiece, where the trippy organ of The Doors, the head cold purr of Julian Casablancas, radio jingle melodies and nonsense ramblings all meet to make something fantastic and easily listenable. At one point Ariel seems to be holding his breath as he croaks ‘Who sank my battleship?/I sank my battleship’.

“I’ve always been interested in the dark side of things and I’ve seen culture absorb these things,” he continues. “There’s an over emotionality in music nowadays – a seriousness and intensity that I believe I had a part in offering up, in the real, brutal dark side. We all like that – when we hear a really deep record, like ‘What’s Going On’, or something like that. Those are things that got me through high school. But people are bastardising that. They took my dark notion and took it too seriously – it’s too melodic out there; we have these references to ‘pop music’, but it’s not pop music. Rhianna is pop, or whatever, but now it mean ’80s synth pop with Beach Boys harmonies. Even the writers write about it as if it’s pop.

“I’m experimental. I’m making some sort of commentary. The joke is on them. I guess it’s pomo, for lack of a better term – you don’t know where the joke starts and where it begins.”

Album track ‘Only In My Dreams’ seems to quash Ariel’s ‘pop’ theory flat, though. The Las, The Shins, The Beach Boys – they all wobble their heads through this golden guitar song. Ariel can surely see the pop in it, even if it doesn’t sound like Rhianna.

“That’s where you can’t draw the line,” he says. “It’s experimental because it’s taking all of that stuff into consideration. As long and you don’t think it’s pop.”

But I do, I tell him. How couldn’t you of a contemporary song so well crafted, melodic and universally sweet?

Ariel pauses for a second. “I like the idea that there’s a certain question in the air about whether I’m going to sell out or not,” he says. “That to me is hilarious, because it completely undoes what I’ve been trying to do, in a sense. I mean, the fact that I could sell out, or even have the capacity to sell out, is constantly a funny thing to me. Of course, that’s my megalomania thinking that everyone is thinking about me. But I would love to sell out, that would be great. Of course, it’s not like I’m selling out in any real sense, because my bank account can vouch for that. I don’t take myself very seriously.”

I ask if Ariel thinks that rock’n’roll does these days – take itself too seriously.

“It’s for kids,” he says. “It’s made by 20-year-olds, and people in their 20s take themselves way too seriously, and they’re preaching to 17-year-olds who then learn to take themselves too seriously.

“I obviously take myself way too seriously,” he adds. “It’s a contradiction. I mean, I’ve had an extended adolescence and I’ve had the privilege to take my adolescence into adulthood a lot longer than most people do. It’s a wonderful gift that’s been given to me. However, do I believe in the same things I did when I started? No. But at the same time there’s no other way to be in this world than living by your priorities and what you believe in.”

Ariel currently lives where he always has, in the city of Los Angeles. That in itself isn’t too unique, but his unwavering love for the city is. I’m sure plenty of residents must live and die quite happily underneath the Hollywood Hills, but people in bands seem to be forever damning the place. Musicians of LA are bona fide in a world of hokey bullshit, wannabe waitresses and unattainable ideals, but that’s not how Ariel sees it. He says: “My music has been a collaboration between my environment and my personality. It was a perfect marriage in a certain sense – a feedback loop that created who I am.”

After wearing out his Deaf Leppard tapes, Ariel became most fascinated with Metallica, “looking at the album covers and thinking, ‘oh, this is serious stuff’,” but he’s always been under the spell of showbiz. “Being down the block from Whiskey-a-Go-Go and Paramount Studios from an early age, it made it almost inevitable that I’d be how I am,” he says. “A key part of that is the dismantling of those illusions. People come to LA thinking they have no illusions about it and then they get disappointed when their fantasy construct has been dismantled. They don’t admit it or even see it that way, but I think LA has a repulsive quality to it, because I always wondered why it wasn’t the centre of the world. It was to me, but I was confused to see how it wasn’t to anybody else. It confuses me even more now because I go around and see that the same things are broadcast everywhere – everyone around the world seems to know LA, so why isn’t everyone there? It makes sense, because it’s a repulsive place to people who go there.

When I ask Ariel what he – a hip, independent musician so ingrained within the realist of real world of DIY culture – makes of Hollywood’s other side (the movies and the glamour) he pointedly replies, “I love it, of course,” as if any other response would be completely unthinkable.

“People shun it because they have ‘humble roots’,” he continues, air-quoting ‘humble’ and rolling his eyes on ‘roots’, “so they don’t want to see themselves as being a manufactured product or a fake product – they see themselves as being real. That’s part of being young, isn’t it, having a fantasy about being real? Those are all constructs. We’re no more real because we’re battered into thinking that we have to get realistic with our lives. We take office jobs because we’re giant kids who’ve been disciplined into thinking it’s the right thing to do. I’ve been disciplined into thinking it’s the wrong thing to do.”

In 2010, after eight years of underground notoriety, Ariel Pink, for many, arrived. He’d already released seven albums of groggy, lo-fi psychedelia, but a substandard live show saw his inquisitive audience lose interest and wane in front of him. “I didn’t know what to do, and I pretty much screwed up in that realm,” he admits. “I didn’t have the standard, I just went on the road with a bunch of friends ready to plug into a stereo. Nobody knew how to play the songs and we managed to alienate all of our audience. People liked the record but not the shows, because we lifted the veil. They where curious enough to get to the show, but we weren’t recreating the record faithfully. I could see my audience dwindling over the years because I also saw it as a necessary evil to play, so my attitude was very alienating to people – I was pissed off and like them, like, ‘this sounds like shit!’.”

With a not-so-merry band in tow, Ariel and friends were attempting to learn and play one-take songs that he’d written before he’d even signed his first record deal in 2002. What’s more, they were trying to stay so true to the on-the-fly nature of the creative process, they were keeping in the mistakes that made those early bedroom recordings. No wonder it sounded like shit. “About three years in I started over,” says Ariel, “because I realised if I wanted to do this and be in the music world I needed to learn to enjoy playing live and start taking it seriously.”

By 2010, Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti had reined in their live show enough to land a record deal with indie giant 4AD, who in June of that year released ‘Before Today’. It finally put Ariel Pink on the indie map, recorded in a proper studio, carrying accessible nods to AM radio pop and cruise ship lounge, and helped along the way by a Pitchfork love-in. It remained a record of old material, though, just recorded properly for the first time, not quite hi-fi, but of a standard that most people could digest and few could point the sell out finger at. Ariel rejects that it’s a good record and welcomes any sell out jibe equally.

“The last record was a big experiment,” he says, “a big failed experiment, in my eyes. The fact that it did so well proves to me that it wasn’t a good record, but I’m proud of everything I do, because I have to be. I don’t put that much stock in that stuff, though, because I feel like every year we’re in the sweepstakes and then we managed to buy ourselves another year of validity, like, ‘oh wow, we’re still relevant’. I thought I was over the hill and out of fashion years ago, and I expect that to be the case any second. Maybe that expectation is what keeps me there a little bit longer, because other people believe their own bullshit and get easily wrapped up. Like, Twin Shadow, 4/10,” he says, pointing at last month’s Loud And Quiet score, “that’s somebody who’s believed his hype from his first record. But whenever you get good press, that’s what they’ll use to chop the next one down, so it’s bad news when you get a 9.0 on Pitchfork [as ‘Before Today’ did]. The next one is going to be 7.5, and I’m expecting that.”

Ariel says that, in view of popularity, he sees ‘Mature Themes’ as “a sophomore effort, if ‘Before Today’ is the first.”

“But I don’t see ‘Before Today’ as being a first of anything in the kind of world that I want to be in,” he notes, “so this is a first in this world I want to be in.”

It’s a belief that he has carried with him his whole career, and perhaps it’s the key to his longevity – a rip-it-up-and-start-again ethos that saves his sanity and can be applied within any one album as easily as it can between them. On ‘Mature Themes’, he seems reluctant to revisit any musical or lyrical idea twice, buddying up the voodoo rumble of ‘Early Birds of Babylon’ and postcard club croon of ‘Symphony of The Nymph’ with the washed out, catatonic ‘Nostradamus & Me’ (vintage Ariel) and robo freakout ‘Is This The Best Spot’. We’re given the effortlessly pleasing ‘Only In My Dreams’ one minute, and ‘Weiner Schnitzel Boogie’ the next – a track through which a sludgy Pink speaks little more than the line “I need schnitzel”, or perhaps it’s “a meat schnitzel”.

“Every single part of the process is a process of killing off what is Ariel Pink,” he explains. “Like, all my early records were the process of me not sounding like me as much as possible, and in the process of that I managed to expand the definition of what me was, and so ‘Schnitzel’ somehow can exist on the same record as ‘Only In My Dreams’, if only because I’ve tried to not make them fit. But that’s just to do with unconscious processes, like the wind and nature and all that kind of stuff.”

Occasionally Ariel trails off like that, ending what is clearly a passionate, well-considered notion with a flippant sign off. I guess it’s the contradictory side of him, or perhaps the insecurity of a modern rock’n’roller.

“I’m all about new beginnings,” he continues, slicing another chunk of steak, “and I tend to disregard everything I’ve done prior. I have what people see as a pessimistic outlook on life, which is really a misreading of it, where I conceive of the worst possible scenario and then when it isn’t that I’m very thankful and grateful. I think of everything as a piece of shit, and as soon as I don’t feel that I think it’s when I start pandering to the bullshit.”

Amongst Ariel’s slew of discarded woozy works is ‘The Doldrums’, his second official album, and the collection of songs that got him on Paw Tracks as the first artist that wasn’t the label’s bosses, Animal Collective. “But that’s just prehistoric,” he says now. “I don’t have any relationship to that anymore, although I can definitely respect the cornels of my own development in that. I really did see it as an experimental scourge on the planet in a very prophetic sense, and that anybody else would see it as such is definitely poetic justice, but it is a scourge because it’s a terrible record; terrible music. It’s anti-progress; it doesn’t have any historical place and that’s the irony – ‘The Doldrums’ coming out in an era where Christina Aguilera is fighting for space with it in a record store. To me, that is hilarious. And I wanted to alienate Pavement fans as much as Christina Aguilera fans – I wanted to alienate everyone with that. The irony is that you have echoes of ‘The Doldrums’ in even Chris Brown and stuff like Rhianna.”

For better or worse, Ariel loves all of his children. Or at least respects them. He refers to his pre-‘Before Today’ records as Where’s Waldo, “jumping up and down in the air shouting, ‘hey, I’m over here, I’m over here!”

“It was really desperate songwriting and I was really making a lot of noise without caring about the results,” he says. “And then I got a little bit of recognition – like, the littlest bit – and that was enough for me to be like, ‘oh, what do I do now?’. Did I have the same drive to do it? No, not really.”

And what about now? What drives Ariel Pink, the blogger’s delight?

“Y’know, I broke up with my girlfriend,” he says in a sombre tone. “That was a big drive to selling out, because I wanted to start a family and stuff, and boy was I wrong about that. My drive now is just to enjoy what you have while you have it, because it’s not going to last. Let’s see if people like this record, which I personally don’t think they will, because it’s closer to the older stuff, and it’s a good record, and good records aren’t appreciated.”

More than once Ariel brings up the fact that all of this could end tomorrow. He respects all of his own failed experiments, but he respects the frivolous nature of the music business more. “I’m stoked that I’m here for another year,” he says, “and I’m happy that this record is a great place to end things, if it is the end.”

He repeatedly returns to the idea of selling out, too, as if any progression from his uncompromising, stringently DIY early songs needs to be defended somehow.

“I’m not necessarily true to my art,” he confesses. “I’m true to life, in that I’m a realist. I want to exist in the world, and obviously just making music and staying pure is not a recipe for success… obviously. Some people have been more pure than I will ever be and they’ve failed, and almost being an artist ensures that you fail, based on the definitions we give it. I don’t want to be that either. If I can sell out, I want to. I want to have as much success as possible. I want to take over the world.”

Ariel’s done the maths and worked out that .07% of the population is currently aware of him and his music, “so we’ve got plenty of people to reach out to”.

I propose that he surely has it in him to sell out if he wants to, and that ‘Weiner Schnitzel Boogie’ is not the way to do it. ‘Only In My Dreams’ and ‘Mature Themes’’s almost as sweet title track probably is, though. If nothing else, Ariel Pink’s extended adolescence as a musician has given him an uncanny knack for creating a nagging melody – even the oddest bits of his new record are more quotable than most tracks you’ll currently hear on the radio.

“But I have principals and priorities in my life that supersede everything that I do in my life,” he argues. “It’s easy to see that humanity has lost its way. Part of me wants to save it, part of me wants to dismantle whatever humanity has gotten us here. We have to redefine priorities and all that kind of stuff, so if I want to be part of that I’ve got to be true to myself.

“Right now we’re a race divided – our biggest threat is other humans and our only hope is other humans, so we don’t know what to do. We are in competition together but we’re no good on our own, and we never have been.”

<DROP CAP>

Shorter, less stringy, slightly hunched and initially shy, Ariel also cuts a fine likeness to Kurt Cobain, snipped from the same outsider cloth. Unlike Cobain, he’s a realist, who, having grown up in fame-hungry Tinsel Town, is well aware of the nature of the beast, and willing to court it when it comes. But like Cobain, Ariel has become a shortcut to a world, whether he likes it or not. Mention home recordings and ‘lo-fi’ and it’ll take approximately five seconds for someone to bring up Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti.

“I definitely want to dispel that,” he says, “because contrary to what people believe, there’s more to Ariel Pink than the sound of something recorded under a mattress. There is actually a patented Ariel Pink groove. There’s a musical expression that goes un-talked about. It’s sort of beyond words because it’s an essence that can’t be grasped. You can’t follow the recipe,” he warns.

Kids do look to Ariel for inspiration, though, just as he did/does to R. Stevie Moore. And so they should. Ariel as a DIY poster boy is no more unfounded than Cobain as a grunge god or Morrison as a spiritual guide. His name is dropped into lo-fi conversation partly because he’s still here after more than a decade, but that in itself is an accomplishment that shouldn’t go unnoticed. And then there’s what’s fuelled Ariel through hundreds of recordings and just as many shitty live shows – an unquenchable need to experiment and a charmed naivety that comes with prolonged adolescence.

“I intended to fail,” he tells me. “I wanted to succeed in isolation but I wanted to fail as the rest of the world was concerned, because that would be confirmation of all the pure things that I ever appreciated in my life – all the best rock’n’rollers were unknown; all the best music was made by people who died completely unknown; all things that affected me were not things that succeeded. If they did succeed they lost that cornel of magic that I’m always looking for.”

Ariel Pink has succeeded, though, and for now, at least, his cornel of surreal, silly, melodic, contradictory, quite brilliant magic remains. And so I ask him what advice he – “a 34-year-old musician who’s still somehow relevant to 17-year-olds” – can offer the kids?

“That’s a good question,” he nods, “but I don’t know yet. I’m dumber now than I was back then. I’ve got more doubts. I was the most confident in my vision before I picked up a guitar. I felt like I had already made all of these records. The way I went around when I was 18 was semi delusional, and yet I somehow managed to achieve those things, like magic. And the more that I learned how to navigate these landscapes the more I’ve learned how incapable I am of executing anything. And you start to think, ‘oh, but it was my total ignorance that got me here’.”