Are You Having A Laugh?

Some people can’t see beyond Mac DeMarco’s flippant one-liners, ironic classic rock covers and adolescent tomfoolery. But this guy is no joke.

Some people can’t see beyond Mac DeMarco’s flippant one-liners, ironic classic rock covers and adolescent tomfoolery. But this guy is no joke.

When Mac DeMarco tells kids that he doesn’t smoke weed, they almost cry. His impression of this terrible news being played out on the face of an expectant teenager is uncanny, and not for the first time today I question just how much longer it will be before the 24-year old stops allowing music to get in the way of his true calling as an actor. “But dude, your music is perfect to hit my bong to,” he pleads in a broken, goofy voice. His lip trembles. His cheeks sag.

Of all the misconceptions that surround him, the most prevalent is that Mac DeMarco is a grade A stoner. At shows fans bring him leafy gifts in polythene bags, which they toss onto the stage at their everyday hero. It’s a sentiment he appreciates, but all that pot goes to his guitarist, Pete Sagar, who’ll comb the stage once they’re done. Suddenly, meeting in Amsterdam doesn’t seem like the no-brainer it once was.

DeMarco has become a master of misdirection – the guy pulling a moony to cover just how hard he’s working. Earlier this year he filled in our Getting To Know You questionnaire. Beside ‘Guilty pleasure’, he wrote, ‘Pissing in the bath’; next to ‘Your biggest disappointment’, he put, ‘My penis’. But DeMarco hasn’t reached 3 acclaimed albums in just 2 years on jokes alone. Knob gags will only get you so far.

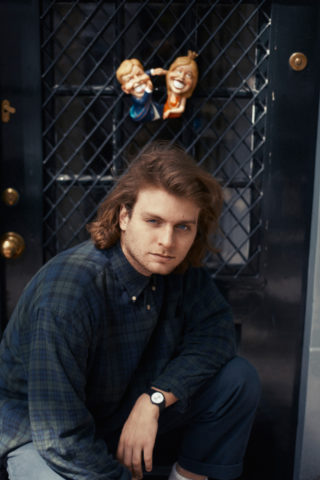

Outside his hotel, Mac DeMarco is instantly recognisable, from his ice hockey hair and plaid shirt down to his too-short worker pants and bright red Vans. He simultaneously looks like a man who’s given up on fashion and one who’s ahead of trend, purposefully carving out a whole new look by himself. Tonight is the opening show of a European tour that for the first time sees him bypass the toilet circuit and make straight for the bigger rooms. “It’s like, ‘only the big fucking shows in the big cities!’” he says, adopting what I quickly realise is a favourite character voice of his – a gruff, burly bark that he assigns to figures of authority, meatheads and villains.

He seems genuinely pleased to see me and we take a short walk to one of Amsterdam’s million cafes for lunch in the sun. He orders water and tells me that it’s a new rule of his not to drink before a show. “It always made me feel like I was going to barf the whole time I was up there [on stage],” he says. “I spent two years feeling like that.” He changes his food order from fish to vegetarian, too, and says he’ll be fitting a little more exercise into his touring schedule from now on.

‘Salad Days’ – DeMarco’s third album – was released a month ago, exclusively to positive reviews, as far as I can tell. He takes my word for it, admitting, “I don’t give a shit to go online and see what people are saying anymore. It’s a bit strange for me.” He says he only read the Pitchfork review and NME’s, later adding Loud And Quiet’s, which is a credit to his good manners.

DeMarco is a friendly guy, willing to talk and naturally funny. His foolhardy onstage persona clearly isn’t a stretch for him, but where you might expect him to reduce all manner of topics to an offhand one-liner, he’s considered in conversation. He puts at least part of his success down to his approachability, saying: “I think what kids connect to is that I come off as a regular guy to them. I’m somebody who they might think, ‘yeah, Mac would drink a beer with me’, and I will, it’s fine. I’m not a cool, indie guy or anything like that. I never have been. I’ve tried to be before in my life; it didn’t work out very well.” He seems happy with his lot, now at least, six month’s after making his “burnt out, weathered album.”

DeMarco wrote and recorded ‘Salad Days’ in a month at home, playing all of the instruments himself, sticking to the formula that created ‘Rock and Roll Night Club’ and ‘2’ in 2012. But by the end of 2013 his ‘Jizz Jazz Studio’ (his bedroom) had moved from Montreal to Brooklyn, and he’d grown tired of solidly touring, having been on the road for the best part of two years.

It’s overly dramatic to say the resulting album is DeMarco’s breakdown record. Even ‘angry’ feels a bit overcooked. But as his familiar guitar lilts like it always has, his voice as lethargic and nonplussed as ever, he’s notably cynical too, about fame on ‘Passing Out Pieces’ and his age on ‘Salad Days’.

“I was unable to write a normal song because I was just thinking about all this crazy shit that had happened to me,” he says. “I remember listening back to some of the songs and thinking Jesus Christ, why am I telling people all of this? I mean, I was terrified to listen to it!

“When I started recording I was pissed off. I was not in a very good head space – unhealthy, feeling sketchy, but what it turned out being was… the album reflects my view points from that time, but if you take a song like ‘Salad Days’, the whole songs is like, ‘man, I’m so jaded, I’m getting older, being on tour is so hard, this shit’s crazy.’ But then the chorus switches over to ‘grow up, you little prick – it’s amazing that this shit’s even happening in the first place!’ A lot of the album, to me, is like a check up on myself. Like, ‘change your tune, dude, you’re being a prick!’

“Even when we started to tour this record, I was like, ‘meh, whatever’,” he says, hunching his shoulders, screwing up his face and talking like a goblin to amplify his resentment. “There was a string of shows where I was calling the audience peasants and shit, and it was really dark. But then there was this one incident where we played a show in Nashville, in a record store, and there was something in that show where I was like, ‘these kids are so psyched, what the fuck is wrong with me?!’ Since that day I’ve felt incredibly good, and all the shows have been good. I don’t know why, but thank God to those kids!”

Hang on, you were calling your fans peasants?

“Yeah, I think they were confused.”

I find this hilarious; DeMarco looks a little regretful as he explains how at the end of his shows his band have been covering ‘Unknown Legend’ by Neil Young, “so I get them all to kneel for Neil Young,” he says. “It’s a fun thing to do, and we’ll probably do it tonight if they call for an encore. Everybody then jumps up for the final chorus.” Pre his Nashville epiphany, DeMarco says he would berate anyone for not joining in, and then, as the final chorus approached he would summon his audience to stand with outstretched arms, shouting, “Rise peasants”. If it was a sight half as funny as the one of him recreating it, I’m sorry I missed it. “So it’s just me being alcoholic, psychopath guy,” he says, and returns to his mineral water.

He says he’s now “gained some level of respect for the people who are spending money on me farting around. They’re not only paying my rent but making me extremely happy. I think it’s just growing up, maybe.”

When I ask him if he’s started to feel old, as ‘Salad Days’ seems to suggest, he says: “I’m planning on never feeling old.”

Mac DeMarco was born Vernor Winfield McBriare Smith IV in Duncan, a small town in British Columbia, Canada, but he grew up in Edmondton, Alberta – the country’s oil heartland; a capital city of brawn. I’m not surprised to hear that it wasn’t the place for him – he left town as soon as he could, first for Vancouver and college, then on to Montreal.

His father wasn’t around, kicked out by his mum whilst – as he told Pitchfork late last year – he was half way through watching All Dogs Go To Heaven – a sad enough film when your parents aren’t splitting up. And so it was DeMarco’s mother who exposed him (and his younger brother, Hank, who is currently studying ballet in Calgary) to everything, including music, from Harry Neilson and The Kinks to The Beatles and psychedelic Frank Zappa movies – “a bonding experience.” Unfortunately, pop country was also high on the list; a genre of wholesome, God-fearing, authentic American music that, fortunately, has never been exported to the UK beyond two Shania Twain songs and the odd ironic appearance from Dolly Parton. “That’s because the English countryside is nice and cutesy,” says DeMarco. “In America it’s, ‘My fucking truck! My fucking chewing tobacco! My fucking muscles! My fucking slut I fucked last night!’” He barks in pantomime jock. “I grew up in a town that was very much like that. I just never really fitted in and it freaked me the fuck out.”

Unless you’re one of them, Canadians call these characters ‘chongos’ – “Weird meatheads who wear shitty tribal design T-shirts and makeup,” says DeMarco, “like Jersey Shore style shit.

“I had some girl friends who’d go to these bars for a joke and there’d be toilets in the middle of the room for people to puke into – just really greasy-ass fucking bar culture. I got the hell out of that town as soon as I finished high school.”

NME, at least, see Edmonton’s working class all over DeMarco, perhaps understandably so when you line him up against current American guitar bands, and especially those on his label – the Brooklyn based Captured Tracks. “I mean, I used to wear skinny jeans, but my ass is too big for them. Look at these,” he says, lifting his foot above the table and reaching inside his trouser leg. “I’ve got room to stick my fucking arm up there. My sperm count is probably up.

“The NME’s funny,” he says. “They always portray me as, ‘Country boy, grease monkey, knows how to fix cars.’ I’m like, ‘not really, but ok,’” he shrugs. “‘Here comes Mac DeMarco,’” he yells like a southern state cowboy, “‘working class and covered in car oil!’”

He doesn’t lose sleep over people getting him wrong, not unless it’s harmful to a third party, and then he’ll set the record straight. That’s rarely the case, though, so if some wish to perpetuate the image of Mac DeMarco the ape-man, so be it. You want to peg him as a stoner? A clown? A joke? Fine. “The more I can confuse people the better,” he says. “Everything else aside from the music I have a pretty good sense of humour about.”

It’s ‘slacker’ that he gets most of all, though, which is perhaps the most inaccurate term of the lot. You only need to see him perform once to grasp how much of a gifted guitarist DeMarco is, although, of course, he does his best to pull focus from that, stripping naked, drinking heavily, calling his audience ‘peasants’. He first picked up the instrument when he was 14 and took lessons for a year; progressing quickly from the AC/DC riffs he initially wanted to learn. He chose to quit and start his own bands when he sensed that his teacher, having noticed his early potential, was trying to turn him into a jazz-fusion guitarist. “Fuck that!” he says.

His first groups were overtly novelty acts; I suspect as a defence mechanism that he still has in place today, in part, at least. The Meat Cleavers took the piss out of chongos, performing shit-fi garage tunes about Nascar and “redneck shit”. ‘Going To The Bar’ and ‘Fuck Me by the Poolside’ are two of their more memorable song titles. The first show they ever played was at a skate park in a sketchy part of town, “hooker central”, after they’d sent joke threatening letters to Edmonton’s local promoters saying, “Give us a show or we’re going to beat the fucking shit out of you.” That the strategy worked only seems to confirm DeMarco’s stories of a hometown up for a fight.

A second group – playing smooth RnB and called The Sound of Love – was then formed to act as DeMarco’s vehicle for wooing girls from his school… or slagging them off for turning him down. “I was kind of a jerk in high school,” he says.

At his shows today, his encores – where he and his band play a medley of ridiculous covers, including tracks by Neil Young, Limp Bizkit and Metallica – have become a draw of their own. It’s the daftest part of the evening and ironically where the true extent of his work ethic is most realised – fucking a guitar whilst shredding ‘Enter Sandman’ is not something easily mastered, and besides, when was the last time you heard of a young guitarist who even took lessons?

“The whole concept of encores is so hilarious and stupid to me,” he says, “so we use it to play covers and do something outrageous. A show’s gotta be a good time. I’m not there to bum people out.”

He finds the term ‘slacker’ a little tiring, essentially because it undermines the effort put into making the music, which is pretty much the only area of DeMarco’s life that is free from gags. “Sometimes I’ll sit down for an interview and the guy’s thinking, [DeMarco adopts his hoarse villain voice again] ‘I’m going to get a kooky-ass interview – this guy’s pretty much fucking retarded’, and then when I can put sentences together they’re like, what the fuck’s going on, this isn’t what I planned. It’s strange,” he says, “but it’s my life now, and I’ve come to accept that.” He ends a lot of sentences in a similar way, sometimes with a simple “… but it’s ok,” emphasising that there are worst things in the world he could be worried about. And he knows that it’s all his own doing, too – his overriding image as village idiot. “If you do something where people have to double take, it makes them pay more attention,” he says, and so when his label suggested that he release ‘Salad Days’ on April Fool’s Day, he just couldn’t resist.

DeMarco has become Captured Track’s biggest artist (a fact that he insists will change as soon as Wild Nothing and Diiv release more music), but last year the two had their first major run-in. He calls ‘Salad Days’ his “therapy” and “meditation”, and considering its underlining theme of a young man coming to terms with new pressures put on him due to his own success, the last thing he wanted to hear from his label was that they needed another upbeat track to pitch to late night television shows. He’d never been asked to change anything before, and when Captured Tracks asked if he could re-record an old song from his previous band, Makeout Videotape, it was like poking a hornets’ nest with a shitty stick.

“When they told me that I was like, ‘Fuck you guys! That’s not cool! You don’t tell your artists that!’ But then you find out that tons of labels do that. I was pissed at first, but I ended up writing that ‘Let Her Go’ song, which is pretty vague, and at that point I was like, ‘you take it or leave it, I’m not changing anything else’. It was weird. When a lot of people who work at the label aren’t even musicians, it’s like, ‘why should I even fucking value your opinion on what I’m doing?’ But I do love those people,” he insists. “They do a really good a job and I do appreciate them.”

Since the disagreement he’s likened the situation to telling an artist that their painting isn’t quite finished. Like I say, the music at the centre of Mac DeMarco’s goofy circus is out of bounds.

“My main goal is to do whatever I want to do. “I love doing this stuff,” he says, referring to our interview and photo shoot, “but the more you get caught up in the industry side of things, the more and more you get pushed around.”

Unsurprisingly, when ‘Salad Days’ leaked a month before its official release, it was the label that was bummed out, not DeMarco, who says he found it interesting to find out which tracks kids were most into without having been told what to think by the music press. “Usually people are like, ‘Oh my god, my album leaked,’” he bawls. “And it’s like, ‘Fuck that shit, man, who gives a shit? It’s done!’. Some people take that so seriously – my label was very bummed out. I remember getting calls from everyone I work with that day saying [serious, whispered voice] ‘are you ok?’, and it really is like, ‘who died? Who gives a fuck!?’ I mean, I understand from their standpoint – sales, blah, blah, blah – but it’s stuff I really don’t give a shit about. If kids want to hear it that badly, I find that cute.”

We settle our bill and leave our chosen café. I remind DeMarco of a time when we spoke on the phone, for an interview we ran in Loud And Quiet 38. ‘Rock and Roll Nightclub’ had just been released. Momentarily, he thinks about politely saying he remembers it. Back then, the joke did extend to his music – a happy accident that produced ‘Rock and Roll Nightclub’: his pervy lounge record of half-speed vocals that made him sound like a deviant Roy Orbison still looking for a good time between sleazy cabaret gigs. “It’s the dirty side of life,” DeMarco had told me. “Show them their dirty underwear.”

‘Rock and Roll Nightclub’ was a surprise hit, but DeMarco was all too aware that it was essentially a gag, so he dialled it back for his following album and wrote ‘2’ (“a normal record”), having managed to give up his grocery store night job and thriftily make a thousand dollar advance from Captured Tracks last five months. People liked ‘2’ even more, and it’s a time he remembers fondly, when he still lived in Montreal with his girlfriend Kiera, who’s quickly becoming as well known as DeMarco due to his public displays of affection and willingness to discuss his relationship in interviews. At Primavera Sound last year, he dived into the crowd to find “Kiki” and serenade her with ‘2’’s closer, ‘Still Together’. It was a touching moment of genuine affection. Then the band performed a cover of ‘Blackbird’ by The Beatles (DeMarco’s a big fan), the death metal way, with bassist Piers shouting absurd lyrics of his own, seemingly made up on the spot, about desecrating the graves of his family. Normal service had resumed. And yet even at these ridiculous times, or perhaps especially when they occur, you can’t help but feel that few other bands possess the musicality to get away with it. Mac DeMarco is an anomaly – a DIY hipster with more than a handful of actual songs; the most overly qualified chancer in Brooklyn.

DeMarco has been pushing the suitable absurd genre of ‘Jizz Jazz’ since we last spoke, although it’s a name that’s yet to catch on. “It’s my response when people ask me what my music sounds like,” he says. “They’re like, ‘well, what’s that?’, and I’m like, ‘well, why don’t you go and fucking listen to it and then you’ll know.’”

We walk along the canals of Amsterdam to take some photos and DeMarco’s heightened alter ego soon springs to life, prompted purely by the presence of the photo lens. “Hullo and welcome to Amsterdam,” he yells in cod Dutch to a boatload of tourists passing under one bridge. He stretches his arms out over the water and steps up onto the railings. The passengers below wave and take photos of their own. It’s refreshing to see a young musician doing anything beyond pouting at the camera, petrified of showing their teeth and looking remotely natural. The opposite is true of DeMarco, who you have to sneakily catch looking straight-faced. I don’t think it’s due to him being so comfortable in the camera’s gaze, but rather that he feels so awkward by it that he crosses his eyes and flails his arms. It’s how he reacts at the thought of anyone wanting a picture of him. I mean, what makes him so special?

Before we walk back to the hotel I give him a copy of Loud And Quiet. Spontaneously, he bursts into a crazed cockney market trader, plugging the wares of our magazine, imploring an imagined audience to “try Loud And fucking Quiet, a great fucking newspaper.” He then does it a second time to allow me to film it on my phone.

We reach his hotel, say our goodbyes and off goes Mac DeMarco, strolling on to a live session in Amsterdam’s red light district ahead of tonight’s show. Once again he is laidback and calm – an approachable everyday kinda guy.

The next time I see him is exactly one week later, on stage in London. He’s spitting water into peoples’ mouths on the front row.