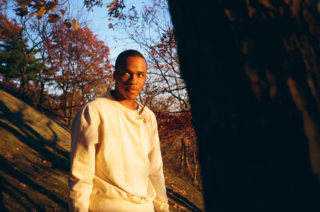

Allan Kingdom always has the look and sound of a man who’s enjoying himself. Whether it’s in the virtual tours of Minnesota the self-appointed guide takes us on in his videos, when he’s springing around on stage with Kanye West at the BRITS or as he talks proudly about how the son of a Tanzanian mother and a South African father found himself growing up in a northern corner of the US, a state full of prairies and forests, the boy born Allan Kyariga possesses a mind that always seems to bubble and fizz. As we talk, there is a fidgety energy to the point where our conversation is punctuated with a string of polite apologies as he censures himself for interrupting time and time again. Despite my reassurances that his effusiveness is a good thing, he seems to be constantly saying sorry and telling me, with noteworthy courtesy, to go ahead.

And yet while he’s dreaming big, he is equally keen to keep his tan leather brogues as grounded as possible. For perspective is crucial to Kingdom’s approach, not only to music but his life in general. “When you grow up with a parent [from Africa],” he muses, grasping for the right words with which to describe the struggles and victories of the main woman in his life, “like, they’re new to this country. So you’re growing up here watching somebody adjust, throughout their own life. My mother is still adjusting to the US to this day. She’s a pharmacist,” he says, his admiration unmistakeable, “and she goes to work every single day but there are still things if you don’t have a childhood here that you still miss. You’re watching someone take a huge risk.” He smiles the first of many smiles and a string of ands illustrate the reverence he has for ‘mom’. “And be a pioneer and step out of their comfort zone; out of where they came from, out of what people expect from them and go even further. So that in itself shapes even how I feel about doing music or being in the game. It’s like, if my mother could make it out of the Serengeti – like, literally – where there’s no electricity, and be here today and own a house in Minnesota… Seeing that leap of faith, I have the same vision for my own career and my sound. Even what I want to do in life. My perspective is a blessing in itself.”

It’s lead to a home culture wherein failure isn’t an option, at least not until you’ve tried your very hardest. It’s informed by a list of lofty family achievements that make his own travails seem insignificant. “My grandfather was the first person in the village to send his daughters to school. Before that the attitude was, ‘Well, she’s going to get married to a man anyways. So she needs to stay home and learn to cook and raise a family, et cetera, so that when she does get married she’ll know how to do all of these things.’” He laughs a wry laugh as he reflects on the effect of his mother on his own work ethic. “So she doesn’t let me have any excuses. Just seeing my mom’s impact and my grandpa’s impact – the children in the village are named after him. That in itself motivates me.”

Kingdom’s heritage has also informed the sound of his latest mixtape and breakout release, ‘Northern Lights.’ A hip-hop record with a remarkably polished pop sensibility, it seems to have somehow crowbarred more choruses than songs into its mere 45 minutes, Kingdom feels he is indebted to sounds that come from east of the Atlantic and south of the Equator. “My mom would play a whole bunch of world music, and I was exposed to a lot of East African music because she’s from Tanzania. I would also hear a lot of South African choirs because my father was from there. He left behind a lot of music that I listened to.” The first member of his family to be born outside of Africa, his hybrid identity has seen him fuse the melodies and rhythms of the continent to modern American music seamlessly. “Just being around that and not really coming from an American musical background, that shapes how I make music. And all of that plays into Kid Cudi, Pharrell, Andre 3000 – all of my pop influences.”

The first big opportunity – and the first real test for a 21-year-old Kingdom – came when he shot to fame after appearing on Kanye West’s 2015 single ‘All Day.’ A Kanye collaboration had been on the list of goals for his nascent career and yet when he speaks about ticking it off within weeks of hitting the legal drinking age, he takes on a circumspect, matter-of-fact tone that suggests there’s a wise head atop those youthful shoulders. It’s not that he isn’t grateful; rather that he realises, acutely, that there’s a lot more work to do. “I feel like it was positive for me,” he ponders, “but that it could’ve been negative. I got the right amount of attention; I got the right type of attention at the right time in my career. Things just happen at the right time when you work for them. I also feel like I didn’t get hype-beasted.” And it’s his self-possession and measured viewpoint that saw him roll his sleeves up and craft ‘Northern Lights’ with painstaking hard work over the course of the last 12 months. “I didn’t go ahead and drop a bunch of singles just ‘cos I did a Kanye song. I took my time and I did this project and it really paid off. I think as an artist people try to make it seem like the public takes you and turns you into something but you do have a say in what you become. I feel like I took the positives from the situation and made it work for me.”

Since then the reaction has been overwhelming but having known Kingdom for all of 25 minutes, I’m already prepared for the considered answer when I ask if success has come as a shock or if he expected respect from the off. “Man, it’s a little bit of both. Because when you put something out you have faith in it. Nobody puts anything out – I feel like it’s kinda bullshit when an artist puts something out and they’re like, ‘I didn’t even know it was good. I just put it out and the world fell in love with it.’” He breaks down in convulsions of laughter before adopting a more sober tone for the wisdom bit. “I feel like that’s corny. When you’re an artist and you truly love what you do, you put your heart and soul into it and you hope that other people will feel the same way about it.”

Kingdom’s contemplative, deliberate approach is evidenced in his lyrics. Colourful sketches of life in Minneapolis’s less fashionable little brother, St. Paul, are cut through with searing, brutal honesty. Whether it’s in admissions of infidelity or his own emotional insecurity, Kingdom seems to be in perpetual pursuit of the truth. “Long term I’ve found that it is easier in life to be honest. It could be easier to lie to you for a couple of months and get my numbers up or it could be easier to lie to this girl about my status and shit but at the end of the day I want people to fuck with me because it’s me.” He reflects on what his words mean, not realising that they belie his 22 years. “The truth always comes to light so it might not be easy at first to just put yourself out like that or it might not be easy to say, you know, that I’m staying at my mom’s house or that I haven’t toured yet, but in the long run it’s very good. It’s less stress when you don’t gotta keep up with all of the lies.”

Concocting his unique brand of urban Minnesotan poetry, he admits, doesn’t come easy. But some subjects come more naturally than others. “I feel like it’s harder to write about my own struggles,” he confesses. “Like sex and women is easier because it’s a natural, instinctual thing. Partying and all that, for me at least – it’s easier to write about things I like because everybody wants to hear it.” As he talks he is at pains to be candid, as though the act of speaking with honesty is cleansing his soul. “For me the hardest thing is to write about my struggles or how I feel left out or betrayed. I always think about the fact that there’re other people who have been through things that are worse and there’s people who have more than I do.”

Acutely aware of his own relative privilege, Kingdom knows that his story might lack the poverty or plenty that so often dominates the rap narrative, but he’s determined not to get dragged off course. “Just talking about my life in general is tricky. Especially in hip-hop, there’s a huge appeal from the guy whose mom was a crackhead, who got shot 48 times,” he grins. “I don’t have a story like that, but at the same time I wasn’t in the street and I didn’t see all these bricks and $100k in front of my face. So just talking about my life, being a rapper and just being a black man in America in hip hop is interesting.”