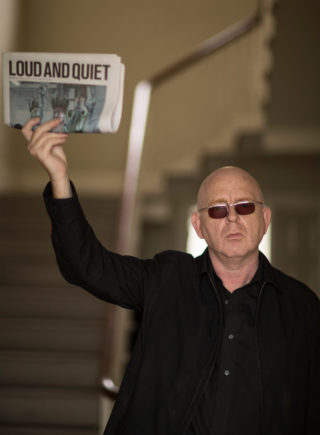

Record Heads: We drove to Wales to conclude our interview series that was inspired by Alan McGee

You'll never believe this, but Alan McGee has some stories to tell

You'll never believe this, but Alan McGee has some stories to tell

I have enjoyed this Record Head series. Simon Raymonde at Bella Union’s enthusiasm still makes me smile. I’ve experienced the fantastic laugh of Rough Trade’s Jeanette Lee, and admired Daniel Miller’s Moog at Mute headquarters. Discussing death with Sub Pop’s Jonathan Poneman was cathartic whilst Peter Thompson at PIAS crackled charisma with a business brain. None of the interviews, though, were as downright funny and honest as the hour I spent with Alan McGee.

These record heads, these pillars of independence, all had something in common. On their own terms, sure, they all possessed a drive to succeed. “I don’t think it just applies to the music business,” McGee is quick to point out. “To be successful at anything is all about will power; having the will to do something is probably stronger than having the love to do something. I have seen a lot of people succeed who are not that talented to be honest. I mean take Bono, he’s not that talented, he’s a good showman but he can’t write a fucking tune.”

Here he is, the old acerbic McGee. The guy from Glasgow not afraid of anyone. He might have got sober and relocated to a quiet corner in Wales but he’s still got fire in his belly. McGee is much more than the mouthy stalwart he’s perceived to be, though. He’s dangerously positive and upbeat about the future, or his future, at least. “I don’t really have a label anymore, we’re doing Creation Management and I am stopping the label thing completely now as we have the Jesus and the Mary Chain and Wilko [Johnson], so I really want to get back into the management side of things. It’s all going to go with streaming and so you might as well just fucking face up to it and just get on with it.

“I am interested in new bands and you are but most people aren’t bothered at all; they’d like to see some pony band from the ’90s do their album 10 or 15 years later. I know everyone has to make a living but it’s fucking bollocks.

“I have just bought a chapel as well; we have got a full license last week. Once the Mary Chain tour finishes this year I can start putting dates in next year for my chapel, it’s just a little venue in the middle of nowhere in Wales. It would probably be in one of the top three strangest venues in the whole of Britain, it’s fucking incredible, y’know? It’s one of the most life affirming projects I have done…”

I cut him off. Not because Alan’s chapel isn’t interesting – I stop him as we’ve been chatting for twenty minutes without mentioning Creation Records once. I haven’t even managed to tell him that his book was the inspiration for Record Head. So we talk about his book for a while and its unflinching honesty. He must have left something out, though.

“There were lots of things I wish I could have included but I think I would have been sued! The thing about rock and roll is that the truth is always stranger than fiction. You could say McGee is a fantasist but the truth really is stranger than fiction. Irvine Welsh is one of my best mates and when he writes, almost all of those stories are true, and he just changes the names. I think people were a bit shocked as [the book] was quite honest about my childhood and about what I came through. The only thing I would counter that with though is that it was probably no different to anyone else who is 54 and from up North – when I say up North I mean North of Watford. There was a lot of abuse but it wasn’t sexual, it was all violence you know, which came from my parents. I came through that and I think a lot of people were shocked that I spoke openly about it, but I don’t think you should hide shit like that. I am opinionated and a lot of people like that, a lot of people hate that, too, so what can you do!? I have had a lot of success, which is great, but it comes from my upbringing; being told you’re a piece of shit or you’re a fucking little cunt, you’re fucking thick and that’s fine but that’s probably what drives me and I have stuck it right up my mum and dad’s fucking arse!”

Creation was independent, but it was never indie. Alan McGee’s pioneering, reckless and fantastically obtuse record label was rock and roll and fiercely competitive. Over a period of a decade and a half, McGee’s temerity and bold taste put him at the forefront of alternative music as he brought us The Jesus and the Mary Chain, House of Love, My Bloody Valentine and Primal Scream amongst others. Before he discovered Oasis he’d brokered a remarkable deal with Sony and made millions. “Yeah, well the record label back in the ’80s and ’90s was all about rock and roll,” he says. “It was about living the life as mentally as you could and having the balls to do it – fuck the consequences and we all did suffer the consequences at some point.”

Alan’s ambition took Creation to places other labels couldn’t reach. With Sony there was a 51% to 49% split in Creation’s favour. “That didn’t mean anything,” says McGee. “At the end of the day they could buy the label off of us if they wanted. The real art was that they wanted to buy the shares off the label, and they tried to buy them for a considerable amount of money and what I managed to do was threaten them enough, saying that I would get such bad press for them, I bullshitted enough and they gave me 14 and a half million to carry on the deal. That was the nineties, that was when people paid stupid amounts of money, y’know.”

The cash came with Oasis. Creation was motoring before the Gallagher’s came along but they’d go much faster, and with that came more partying and more excess, at a time when McGee’s escalating drug use took him to the edge. “I mean, that was going on since about ’87, from my marriage break up. I was told by my first wife that I was a loser, which was probably a bit hard to swallow by about 1995 when I was the king of Britpop, but never-mind. I probably started drinking and taking drugs around that time and then I kind of collapsed in ’94 and then got myself together at the end of ’94 and carried on, y’know.”

Do you regret missing the Brit-Pop party then Alan?

“No! I was there,” he balks in disbelief. “You can’t read into what you see in all these documentaries, you know? I was missing for 9 months in 1994, from February and even then I would see Noel for dinner and he’d come round my house while I was rattling from too many prescription drugs, you know. I was out of rehab by October and back working by November, so I was only really out for about 9 months and then I saw the rest of it. I did see the rest of it sober, though, and I watched them party and I have got to be honest, watching them party made me feel good to be sober!”

By now, McGee is in full flow. There’s a refreshing lack of modesty in his storytelling but it somehow feels true rather than boastful.

“I come from fuck all in Glasgow, I went to comprehensive school, my mum was a shop assistant and my father was a panel beater. If I didn’t end up doing music, what would I have ended up doing? I would have probably been a criminal, to be honest. I would have probably got into credit card scams or something like that. I was OK at football, but I was never going to play for one of the big teams; the only the thing I was any good at was music and if that didn’t work out well we know crime pays, I mean, look at the bankers, do you know what I mean, it’s like they’re the new rock stars.”

Talk turns back to football, Alan being a Rangers fan from an early age.

“I was OK, you know. I mean, did you ever watch that show Soccer AM? That thing with the hole in the wall, I only went and scored. I sent it to Noel who didn’t comment but Liam did say, ‘fucking hell, I am never going on that show if you scored, I will look like a right cunt if I don’t score and you do.’”

That angry 16 year old from Glasgow, what would he have thought of his famous trip with Noel to Downing Street at the height of his fame?

“I think we both got a bit of shit, didn’t we? I have got to be honest, I don’t give a fuck about what anybody thinks, anybody at all, except maybe my daughter.”

What about modern politics then, and the recent Scottish referendum for independence?

“If you call that a legitimate election then you are on drugs. I mean, Scotland will never be able to be let loose as they’ve already sold that oil twice over, do you know what I mean, so we were never going to get out. Scotland has had enough, there’s something like half a million people going to banks or on benefits and it’s fucked. It’s not like London; it’s the opposite of that.

“I am not a hypocrite; I live in a really nice posh hotel when I am in London and I live in a fucking mansion with 26 acres in Wales. I have had it large and I am living it large, but at the end of the day my sisters live in Scotland and if I didn’t support them, one of them, for a start, then I don’t know how she would get through.”

It’s astonishing how far McGee’s influence spreads. Recently we’ve seen The Libertines reform, a band Alan managed through their tumultuous second album. My Bloody Valentine have also returned after a 22-year absence. “Aye, almost every cunt,” is his typically droll reaction.

Infamously, the two-year long recording of MBV’s ‘Loveless’ nearly bankrupted Creation and McGee seems reluctant to talk about such a seminal work. “I don’t listen to ‘Loveless’ but I am mates with Kevin [Shields],” he tells me. “I had dinner with him unbelievably a couple of months ago in Dublin – we’re good with each other. Bizarrely, in some ways we are quite alike – we are both totally single minded. For Kevin, [releasing ‘m b v’ in 2013] was fantastic; he didn’t compromise and it was everything he said he was going to do. He told everyone to go fuck themselves and he put it on the website, which was fucking great.”

For a man who supposedly rubs people up the wrong way, McGee is known most of all for his loyalty. He keeps his friends, although he didn’t see Carl and Pete take to the stage again. “I was so happy for them,” he tells me. “They’re a brilliant band. I was probably wrong trying to clean up Peter – I should have let nature take its fucking course – but if caring about somebody is wrong… I tried to clean him up and all I tried to do is keep someone alive, so you know…”

But the band closest of all to McGee is one he never gave up on – Primal Scream.

“I really love them,” he says. “I mean, it’s a pity as I never really see Bobby anymore, he could basically be kind of like…” McGee falters. “I mean, I live in Wales he lives in London – it is what it is, but there is a lot of love there. They were my friends growing up, you know, and it’s terrible that Robert died. Unfortunately it was when my wife was in Africa so I couldn’t actually make it to the funeral, but yeah, that kind of got to me a bit because he never made it to 50. Sometimes you can be too strong, luckily with people like me, Bobby [Gillespie] and Andrew [Innes], we were weak and we all fucking collapsed through drugs at one point or another and all got clean, but with Throb being the horse that he was, he just kept going.”

We end where we started, and that’s talking about family and death. For such an upbeat conversation our own mortality comes up over and over again, I tell McGee. “Well, my family died in their ’50s,” he says with a raw of laughter. “My mum died when she was 54, my granddads died when they were 56 and 58, so you know, if I live another ten years then I will break a world fucking record. I’m going out with a bang that’s for sure, I’ll die managing a band, that’s it, I will probably die managing some weird little band.”