O

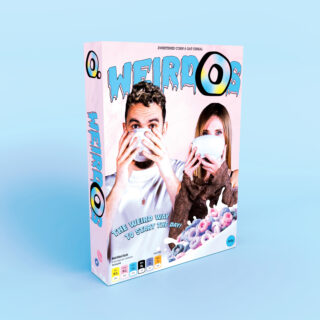

WeirdOs

8/10

8/10

Bear with me for a minute as we go down a rabbit hole. Let’s talk about saxophones.

Culturally speaking, the sax has been on a journey, fluctuating from centre-stage icon to sad, weird things that only band nerds play. Invented in 1842 by Adolphe Sax (genuinely), it spent its first 80 years as a musical curiosity. It wasn’t until the 1920s that it started making a splash in the hands of jazz bands like The Duke Ellington Orchestra, and remained a mainstay of popular music until the early rock era. In fact, Ike Turner’s group King of Rhythm, responsible for Jackie Brenston’s ‘Rocket 88’ in 1951, arguably the first proper rock and roll song, had a sax part, putting forward the case that the early history of rock and roll was built on the saxophone. Well, until the Brits showed up. In the mid to late ’60s, the saxophone was not a feature when British pop exploded and took over the world. The Beatles didn’t have one, and the Rolling Stones only dabbled with them. As music became more guitar-driven, the saxophone was relegated to the sidelines, neither phallic enough to be seen in the hands of a proper ‘rock’ frontman nor technologically advanced enough to compete with the rise of the synthesisers. Apart from a brief period in the ’80s when the retro sexy sax player became ubiquitous, (see Clarence Clemons ripping it up in the E-Street Band or a ripped Tim Cappello doing his thing in the first 20 minutes of the movie Lost Boys), the saxophone was relegated from pop into the misfits’ league.

The cool kid’s loss has been the weird kid’s gain, though, and the saxophone’s rejection to experimental music has only shown how versatile an instrument it is. Able to produce both smooth and rough tones in a vocalising or harmonising manner, the sax is one of the few instruments that can almost mirror the human voice, easily embodying emotion and soul. Since the 1970s, underground musicians have taken advantage of this relentlessly. It can be made to sound paranoid, such as Wayne Shorter’s playing on Mile Davis’s Bitches Brew or King Crimson’s ’21st Century Schizoid Man’. It can sound dangerous, like on The Stooges ‘Down on the Street’ or Rocket From The Crypt’s ‘On A Rope’. And in the hands of no wave legend James Chance (RIP) or the Jesus Lizard, it can sound absolutely deranged.

It has been many years since the saxophone has been taken to the limits that South London two-piece O. seem willing to take it to. A lockdown project launched in 2020 made up of Joe Henwood on sax and Tash Keary on drums, everything about them feels like a contradiction. Two classically trained musicians with a background in jazz, their music is the epitome of plug-in-and-play DIY, designed to be thrown on stage in a hurry and consumed stripped down in a live setting, where the visceral interplay of sax and drums can be witnessed to the fullest. However, there’s more to the duo’s music than loud, vaguely psychedelic rock fashioned from parping horns and bezerkoid drums. Instead of being limited by their simple set-up, O. has turned to melody, compositions, loop pedals and distortion to make up for the lack of dynamics. While their music might sound vaguely familiar, with hints of ESG and dub reggae in places, any trope or nod to genre is thrown around with the disdain of a Top Gear presenter razzing around in a family hatchback. O. are one of those rare bands that do not seem beholden to obvious influences and are unafraid to stretch and pull conventions apart, revealing that even the most tired post-punk tropes can be surprisingly stretchy, as long as you’re unafraid to lean on them.

While O.s reputation as a live band means that they’re pretty easy to catch if you’re willing to dip into South London, it does mean that they haven’t put out much in the way of recorded output, despite four years of songwriting and activity. Last December, the band put out SLICE, an EP of four songs on Dan Carey’s Speedy Wunderground label that showed just what a saxophone can do if you loosen the shackles. However, WeirdOs, the band’s first full-length, shows what happens when you fully let the thing loose.

This is the sound of a band that has just said ‘fuck it, let’s try it’ to every zany idea they could come up with. Every song on this record has something left field going on. ‘TV Dinners’, for example, is what happens when you slap a distortion pedal on a saxophone, get bored, and then hook the thing up to a wah-wah instead. On the other hand, ‘Green Shirt’ compresses the thing until it sounds like a SEGA game soundtrack before dropping into sludgy metal with a riff that seems ripped from an old Limp Bizkit breakdown. The tonal shifts come so thick and fast it’s overwhelming to take in on first listen, and it’s been a while since I’ve heard an instrumental record that can swerve between Jungle-style breakbeats, spaced-out cosmic jazz and Black Sabbath style doom without coming across like a big chaotic mess.

A big part of that coherence comes courtesy of Keary’s drums. In the same way that Henwood wrings almost everything out of the saxophone, Keary does the same with her drum kit. Deploying every trick in the book, from paradiddles and rim shots to syncopation and fill-laden blast beats, the beats on WeirdOs keep you guessing as much as the saxophone lines do. In fact, one of the most fun things on this album is the sheer equality between the two instruments. Usually, the dynamic between drums and melody is that one leads and the other follows, but it’s never easy to work out which is doing which in O.’s case. The song ‘Whammy’ is a case in point, effortlessly shifting between ‘verses’ where a sneaking, tap, tap, tapping drum part is the star, and a full-on horn blasting ‘chorus’ driven by a regular 4/4 beat delivered with the same raw power as a stadium rock band.

As tempting as it is to sit here and list out all the musical virtuosity and clever compositions on display, the absolute best thing about this album is that it never stops being fun. Sticking closely to O.’s DNA as a live band first and foremost, every song in the 40-minute runtime bangs in its own way. Like a wedding DJ set, this record ranges in genre, tone and tempo but remains focused on delivering pure joy. And in a world where it sometimes feels like you’re being bombarded by emotionally heavy, lyrically meaningful tracks demanding your full attention, it’s refreshing to come across an album that asks nothing more of you than to go with it. Maybe, we need more bands like O., willing to set aside being cool, say fuck it, and just play a saxophone for all it’s worth.