The legend of Serbian factory worker Abul Mogard, and other cult origin stories

A look into the hoaxes and dubious genesis tales of cult musicians

A look into the hoaxes and dubious genesis tales of cult musicians

Abul Mogard was born in Belgrade, Serbia, and spent most of his life working in a metal factory. When he retired he began to miss the clunk, clatter and rhythm of the sounds that punctuated his day. So he began to make music, experimenting with a synthesizer to reimagine the lost sounds of his environment – the whirs, immersive drones and hissing ambience. The results were incredible and releases began to stack up. Glowing reviews came pouring in and you could read gushing articles, such as a deeply personal essay on Medium that someone wrote entitled “The Calloused Hands of Abul Mogard”, in which the author talks about how he relates to the Serbian’s music due to the working class ethics and approach that permeates throughout his records.

The music of Mogard didn’t so much replicate the literal sounds of factory life but instead captured a tone and presence that was absent in Mogard’s life since he left; the music represented a longing and loneliness felt since he stepped out of factory life as he spent his days at home alone. It was a nostalgic musical tribute to the beauty of the toughness of factory life. This sense of isolation was not just clear through the eerie, dense atmospheres and engulfing clouds of thick electronics that coat the records like a moorland fog, but also due to the fact that Mogard never truly embraced his newfound role as a celebrated cult artist. Interviews were sparse and whenever they took place were clearly done via email. Live shows were just as rare and when he did appear to perform at Berlin Atonal in 2017, he did so under a blanket of smoke and lights so dense that he was barely recognisable.

However, to look at the image of him from that show, behind all the smoke and lights, it starts to resemble a much different shape and form to the photograph of Mogard that exists: a bald, stocky, elderly man. Combine this with the very prolific nature of Mogard and the incredibly contemporary tones that emanate from his records and people began to question this story and character. Asked for comment from Mogard and his record label about his identity around yet another new release (the remix record ‘And We Are Passing Through Silently’) and there’s a big fat ‘no comment’, as there always has been. Rumours are plentiful about the true identity of the supposed factory worker, but the underlying consensus in the world of underground electronic music is that this is a load of bullshit and there is no Mogard.

Mogard is just one of many artists that have taken this approach over the years – to essentially create a fake identity to filter music through. Another recent similar example is the Kosmischer Läufer records, the first volume (which now stretches to four) of which was released in 2013. The story goes like this:

In East Germany in the early 1970s, Martin Zeichnete worked as a sound editor for DEFA (Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft), the state-owned film studio. Like many young East Germans of the time he would listen furtively to West German radio at night and became infatuated with the Kosmische Musik or ‘Krautrock’ epitomised by the likes of Kraftwerk, Neu! and Cluster emerging from his neighbouring country. Martin, a keen runner, hit upon the idea of using the repetitive, motorik beats of this new music as a training aid for athletes. He thought it could benefit the mind as well as the body with the pulsing, hypnotic music bringing focus. A ‘borrowed’ prototype of Andreas Pavel’s Stereobelt showed Martin the technology to provide music on the move already existed and could easily be adapted for runners.

After sharing his concept with colleagues Martin was taken from his studio to East Berlin, quizzed by the authorities about his ideas and, fearing the worst, was surprised to find himself put to work by the Nationales Olympisches Komitee immediately. Installed in a cold Berlin studio with the few electronic instruments the state could supply (Martin asked for a Moog but was refused), he began one of the strangest journeys in music. Known to the government as State Plan 14.84L, Martin and his fellow musicians informally called it ‘Projekt Kosmischer Läufer’ (Cosmic Runner).

After sharing his concept with colleagues Martin was taken from his studio to East Berlin, quizzed by the authorities about his ideas and, fearing the worst, was surprised to find himself put to work by the Nationales Olympisches Komitee immediately. Installed in a cold Berlin studio with the few electronic instruments the state could supply (Martin asked for a Moog but was refused), he began one of the strangest journeys in music. Known to the government as State Plan 14.84L, Martin and his fellow musicians informally called it ‘Projekt Kosmischer Läufer’ (Cosmic Runner).

For the next 11 years Martin would be spirited to Berlin to work on tracks with little notice. He created hours of music fusing traditional rock instruments with synthesisers, early drum computers, tape slicing and looping techniques he and his engineer formulated themselves. His output included tracks for running at various paces, warm up pieces, ‘ambient’ music to play in gyms during training and pieces for artistic gymnastic routines.

That’s the story.

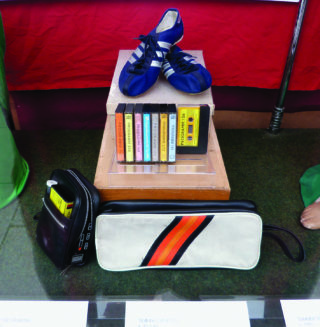

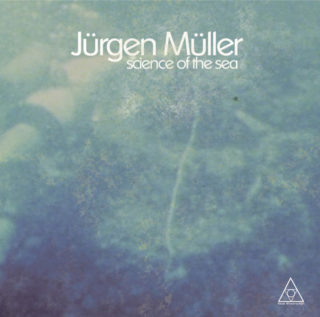

This hoax was so elaborate they even made fake original cassette tapes and set up an exhibition that included such items as clothing that athletes wore in the supposed athletic program. The music has received rave reviews, many editions are now sold out, and it has been performed live by a band including Yann Tiersen. Then there’s Prurient’s Dominick Fernow releasing music as Rainforest Spiritual Enslavement that was initially described as being part of a series of cassettes found in Papua New Guinea – lost recordings of a group of missionaries that supposedly disappeared back in the ’80s. And there’s the Seattle-based composer Norman Chambers, who dreamed up a story of the scientist Jürgen Müller making electronic music out at sea.

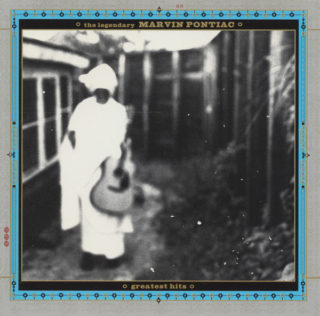

Then, back in 1999, there was the remarkable story of Marvin Pontiac, about how he was hit and killed by a bus in 1977. Born in 1932, he was the son of an African father from Mali and a white Jewish mother from New Rochelle, New York. The father’s original last name was Toure but he changed it to Pontiac when the family moved to Detroit, believing it to be a conventional American name. Marvin’s father left the family when he was two years old, but when his mother was institutionalised in 1936 his father returned and brought the young boy to Bamako, Mali, where Marvin was raised until he was fifteen.

The music that he heard there would influence him forever. At fifteen Marvin moved by himself to Chicago where he became versed in playing blues harmonica. At the age of seventeen, Marvin was accused by the great Little Walter of copying his harmonica style. This accusation led to a fistfight outside of a small club on Maxwell Street. Losing a fight to the much smaller Little Walter was so humiliating to the young Marvin that he left Chicago and moved to Lubbock, Texas, where he became a plumber’s assistant. Not much is known about him for the next three years. There are unsubstantiated rumours that Marvin may have been involved in a bank robbery in 1950. In 1952, he had a minor hit for Acorn Records with the then controversial song ‘I’m a Doggy’. Oddly enough, unbeknownst to Marvin and his label, he simultaneously had an enormous bootleg success in Nigeria with the beautiful song ‘Pancakes’. His disdain and mistrust of the music business is well documented and he soon fell out with Acorn’s owner, Norman Hector. Although, approached by other labels, Marvin refused to record for anyone unless the owner of the label came to his home and mowed his lawn.

Reportedly, Marvin’s music was the only music that Jackson Pollock would ever listen to while he painted. In 1970 Marvin believed that he was abducted by aliens. He felt his mother had had a similar unsettling experience, which had led to her breakdown. He stopped playing music and dedicated all of his time and energy to amicably contacting these creatures who had previously probed his body so brutally. When he was arrested for riding a bicycle naked down the side streets of Slidell, it provided a sad but clear view of Marvin’s coming years. In 1971 he moved back to Detroit where he drifted forever and permanently into insanity.

The album came loaded with hyperbolic quotes too. “A Revelation,” according to Leonard Cohen. “A dazzling collection,” said David Bowie. Whilst, apparently, Flea grew up learning bass to his records. The reality was much more straightforward, however: there were no fights, institutions, moments of insanity or anyone from Africa singing. It was all a project by John Lurie, the actor and artist best known musically for co-founding the jazz outfit the Lounge Lizards.

Whilst the stories of alien abduction might have been a red flag for some, people – including several journalists – did believe the hype and the story, and ran reviews accordingly. Years later Lurie told Perfect Sound Forever: “There were a few journalists who were duped by the hoax and they were angry. Mostly white guys [Lurie is white] saying it was wrong to pretend to be black, but I found out that two of them had done these rave reviews on it until their magazines told them that it was me and that it wouldn’t be credible to run their article about the insane African bluesman who had been rediscovered.”

There is of course perfect validity in suggesting Lurie adopting the character of a deceased mentally ill African man to sell records is crass, even if he felt the whole thing was nothing more than a giggle at the time to avoid the repetitious mundanity of the album campaign press cycle. “I had to send bios to people [for the record],” he said of the decision. “I hate beyond hate doing that. It was immensely more fun to do it this way.” Twenty years later, time of course has changed and whilst Lurie returned as Pontiac in 2017, he did so under no pretence; no longer trying to keep up the story.

There is of course perfect validity in suggesting Lurie adopting the character of a deceased mentally ill African man to sell records is crass, even if he felt the whole thing was nothing more than a giggle at the time to avoid the repetitious mundanity of the album campaign press cycle. “I had to send bios to people [for the record],” he said of the decision. “I hate beyond hate doing that. It was immensely more fun to do it this way.” Twenty years later, time of course has changed and whilst Lurie returned as Pontiac in 2017, he did so under no pretence; no longer trying to keep up the story.

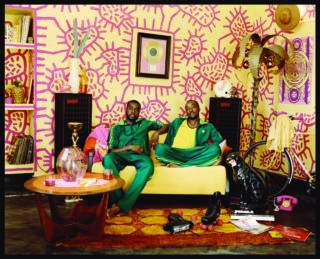

You would think this is because during current times being a white artist essentially pretending to be black in any context is a no-no. However, sadly that hasn’t stopped other artists adopting such images in recent years. Remember when the only promo photo for the mysterious unnamed duo Jungle (known simply as J and T) was a photograph of two hip-looking black men? Only after endless buzz and being dubbed “the hottest band in Britain” – i.e. when they had traded off the image of being black for a sufficient enough time that they had succeeded – did they reveal their true identity: two white dudes with laptops who were having a go at making funk-tinged electronic pop after their previous self-described “indie dross” had failed.

Bafflingly, it seemed to – and continues to – not bother anyone. The press kept coming; the gigs; the reviews; the creeping up the festival posters. However, would the music of Jungle really, truly have taken off in the way it did if it was presented honestly by the creators from the off? Would two white guys from a failed indie band who went to a £20,000 a year private school, knocking out generic laptop music, have been the buzz band of the year?

Similarly, as fantastic a live band as the Swedish psych outfit Goat are, would they have reached such prominence and attention if it weren’t for the elaborate tribal outfits, face masks and accompanying press releases claiming they are from a remote village and practice voodoo (an unconfirmed story that remains so because they refuse to do anything other than email interviews, with the exception of very rare phoners)?

Anonymity is of course a magical and alluring pull in music. Just look at an artist like Jandek, the cult avant-folk/blues musician that has been releasing records as an unknown entity since 1978, and who didn’t perform publicly until 2004. Between those dates he had conducted just three interviews. Over that period of time his status as the ultimate reclusive artist was so embedded into his musical output that the concept of him existing as a public figure seemed at odds with what people had spent decades immersed in.

Identity is a complex thing in the social media age. There are of course perfectly valid arguments that even artists who present themselves under their own name still do so through an elaborately calculated and managed sense. In an era when bands and artists spew out meaningless hashtag politics to score online woke points, is it any less fake to simply lie about your entire existence under the guise of character? It balances an interesting and occasionally perilous line between exploring identity and being exploitative; between wily marketing and desperate tactics to do what it takes to get yourself heard and seen. So it asks the question: playfulness or perniciousness?

When I spoke to BBC 6 Music presenter Mary Anne-Hobbs in 2017 for The Quietus’ Baker’s Dozen feature (people pick their 13 favourite albums of all time) she selected ‘Circular Forms’ by Abul Mogard. “I don’t actually care if it’s a fictional story or if it’s true,” she told me. “For me that narrative and the nature of the music work perfectly harmoniously. I love it. I was a factory girl myself – when I left school at 16 I worked in a factory for a year. There’s a romance to it. Usually once a story has been contested then the truth will float to the top, but with this instance the truth has been contested with me several times and no alternative truth has been presented as yet, so I like to buy into it.”

So does buying into the myth, as long as the music is good, supersede a need for truth? Does authenticity matter if the yarn or the art is good enough? A cursory glance at Kosmiche Laufer’s Bandcamp page suggests not, with various albums, T-shirts, cassettes and packages all glowing red in the words: Sold Out. Drew McFadyen of Unknown Capability Records (the likely person behind the music) was willing to speak about the project. “Everyone is absolutely entitled to their opinion on this music and its origin,” he says, adding cheekily: “Sometimes I don’t believe Martin’s story myself.” He tells me that they have never had a single request for a refund or a complaint that the project is fake. Whether people willingly buy this knowing it’s fake but love the music anyway, or are clinging on with a slither of hope that it might be real, it makes no difference to McFadyen. “If people take Martin’s story at face value and think it’s some art project, or a steaming pile of sauerkraut but still love the music, we are happy to accommodate. All views are welcome here.”

The underlying question around all of this remains, of course: why? Pretending to be a retired Serbian factory worker is of course not the same as racial or cultural appropriation but they are linked and the answer is somewhat axiomatic in the fact that articles like this are being written. More pieces have been written about this kind of music because of both its backstory and its likely fakery than ever would have been written if some Scottish band started knocking out some retro 1970s German music. The real answer to this approach arguably comes when McFadyen is asked about the ongoing success of his project, as volumes continue to sell. “It’s been very satisfying to see the music spread naturally through word of mouth. Thankfully, as the advertising budget has been, and remains, zero.”